ANALYSIS: By David Robie, convenor of Pacific Media Watch

While Pacific countries have got off rather lightly in a major global media freedom report last month with most named countries apparently “improving”, the reality is that politicians are becoming more intolerant and belligerent towards news media and information “black holes” are growing.

The Pacific is at the milder end on the scale of media freedom violations – there are no assassinations, murders, gaggings, torture and disappearances.

But the global trend of “hatred of journalists [degenerating] into violence, contributing to an increase of fear” warned about by the Paris-based global watchdog Reporters Without Borders is being reflected in our region.

READ MORE: Pacific countries score well in media freedom index, but reality is far worse

Lack of safety for journalists is a growing concern for media organisations around a world where 80 journalists were killed last year, with 348 being jailed and 60 held hostage.

At least 49 of the slain journalists were “deliberately targeted” because they were media workers.

“If the political debate slides surreptitiously or openly towards a civil war-style atmosphere, in which journalists are treated as scapegoats, then democracy is in great danger,” says RSF secretary-general Christophe Deloire in the introduction to RSF’s annual World Press Freedom Index.

“Halting this cycle of fear and intimidation is a matter of the utmost urgency for all people of good will who value the freedoms acquired in the course of history.”

Global concerns

The global concerns have been echoed in the Pacific in recent times.

In Papua New Guinea last week, for instance, amid what appeared to be the unravelling of Prime Minister Peter O’Neill’s coalition government – described by many critics as a “dictatorship” – with the defection of seven members including the finance minister and attorney-general, an opposition leader made an extraordinary threat against the country’s two foreign-owned newspapers.

Vanimo-Green MP Belden Namah, leader of the PNG Party, one of the two major parties in the opposition, put the Australian-owned Post-Courier and Malaysian-owned National newspapers “on notice” that a new government would “deal” to the media.

Angered by the two dailies for not running his news conference stories, he threatened to regulate the print media if a new government is installed in vote of no-confidence due on Tuesday.

Last November, one of Papua New Guinea’s leading journalists, EMTV’s award-winning Lae bureau chief Scott Waide, was suspended by his company under pressure from the O’Neill government to have him sacked.

Why? Because he exposed the “inside story”of a diplomatic Chinese tantrum and a scandal over the purchase of a fleet of luxury Maserati cars during the Asia Pacific Economic Forum (APEC) hosted by Port Moresby.

Writing in Pacific Media Watch, columnist Vincent Moses thundered:

“Peter O’Neill is acting like another Chinese dictator in Papua New Guinea by exerting control over both state-owned and private media to not report truths and facts that expose his government and their corrupt acts to PNG and the world.”

‘Huge attack’

“This is a huge attack on media freedom in PNG and must be condemned by everyone,” Moses added.

The strong condemnation that followed forced EMTV to reverse its decision and the network reinstated Waide.

Ironically, Papua New Guinea’s Index “freedom” score lifted it 15 places to 38th in the global list of 180 countries.

Other Pacific countries and Timor-Leste also improved in the report assessing 2018 – except for Samoa, which was unchanged at 21st (just one place behind Australia). But this improvement must be seen against the background of global deterioration of media freedom.

The qualitative assessments in the index report make it clear media freedom in Pacific countries is also declining, just not as rapidly as in many other countries.

In the North Pacific, a Pacific Island Times magazine editorial last month blasted the traditional chiefs on Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia for demanding the expulsion of a probing US reporter as harassment and an attempt to “silence a journalist”.

The magazine’s editor-in-chief, Mar-Vic Cagurangan, strongly defended her Yap correspondent, Joyce McClure, who has been living on the island for the past three years, saying that declaring her persona non grata would set a “dangerous precedent”.

Joyce McClure’s reporting provided transparency, which was “vital to every democratic society”.

‘Truthful information’

“The Pacific Island Times and Ms McClure have no agenda other than to provide truthful information to the people of the Pacific region. She is doing this job not as an outsider but as a member of the community, which has become home to her,” the Times said in its editorial.

Stories that McClure has written include reports on a private company’s apparent attempt to bribe newly installed state officials. She has also exposed Chinese commercial vessels harvesting Yap fish with local help.

The Yap media freedom saga was well documented last week by my Pacific Media Watch colleague Michael Andrew in his Bid to Expel Journalist report.

This week, on Wednesday, the Times reported that Joyce McClure “won’t be kicked off the island” as demanded by the chiefs.

“And questions are being raised about the legitimacy of the letter conveying the chiefly demands to the Yap State Legislature and then on to the Federated States of Micronesia Congress,” the Times added.

Replying to questions from Pacific Media Watch, Cagurangan admitted the stakes are high for small and vulnerable “self-funded” independent island publications such as Pacific Island Times.

“During last year’s elections [on Guam], the campaign team of then candidate and Bank of Guam president (now governor) Lou Leon Guerrero signed a political ad contract with us,” she said. “Despite the signed contract, the campaign team pulled out their ad following the publication of an op-ed piece written by a guest writer, which displeased them.

“Although we rely on advertising revenue to keep going, we refuse to compromise our journalistic integrity and independence.”

Malolo environmental expose

In Fiji, an independent New Zealand website, Newsroom, investigated a major environmental development disaster by the Chinese company Freesoul real Estate on the remote tourism island of Malolo, exposing how Fijian news media had been effectively gagged by 13 years of draconian media legislation and a climate of fear since the 2006 military coup.

Although democracy has returned and two post-coup elections have been held, the most recent last November, journalists are often intimidated into silence.

Opposition Leader Sitiveni Rabuka, the man who staged Fiji’s first two coups in 1987, said the “rot and culture of fear” in the civil service and the “intimidated and cowed media” were now so ingrained in the country that it had taken foreign journalists to break the story.

The three New Zealand Newsroom journalists reporting about Malolo were arrested early last month but Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama ordered their release a day later and apologised to them personally for their ordeal at the hands of “rogue officers”.

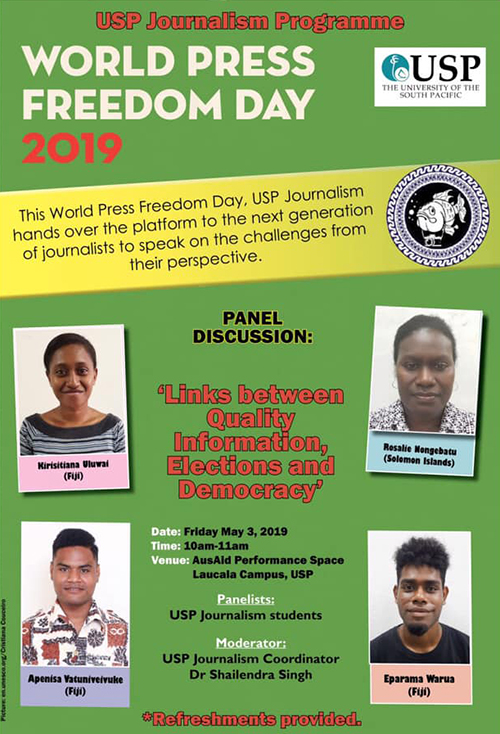

The intimidation of the Fiji media is an issue that the editor of the award-winning Wansolwara student journalist newspaper, Rosalie Nongebatu, and three of her fellow students will address at a World Press Freedom Day seminar hosted by the University of the South Pacific today.

Censorship, intimidation

About the Asia-Pacific region, the RSF media watchdog warned in its report that totalitarian propaganda, censorship, intimidation, physical violence and cyber-harassment meant that it now took a “lot of courage … nowadays to work independently as a journalist” in the region where democracies were struggling to resist various forms of disinformation.

It singled out China and Vietnam, which both dropped one place to 177th and 178th respectively on the global list of 180 countries, as the worst culprits (although the bottom placed country on the index is now Turkmenistan).

About 30 journalists and media workers are detained in Vietnam, with nearly twice as many being held in China, a country of major concern to the Pacific in view of the growing economic, aid, trade and strategic influence in the region.

“China’s anti-democratic model, based on Orwellian high-tech information surveillance and manipulation, is all the more alarming because Beijing is now promoting its adoption internationally,” said the RSF report.

“As well as obstructing the work of foreign correspondents within its borders, China is now trying to establish a ‘new world media order’ under its control, as RSF showed in its latest special report on China.”

The RSF Index report sees the growing raft of cyberlaws – such as in the Pacific – as an example of this Chinese-inspired media manipulation.

Special mention was made of the Philippines, whose President Rodrigo Duterte is one of the world leaders – along with US President Donald Trump – most consistently spreading “hate” towards journalists.

‘Silenced with impunity’

“When sworn in as president in June 2016, Duterte issued this cryptic but grim warning: ‘Just because you’re a journalist, you are not exempted from assassination, if you’re a son of a bitch. Freedom of expression cannot help you if you have done something wrong.’”

Three Philippine journalists were killed in 2018, “most likely by agents working for local politicians, who can have reporters silenced with complete impunity”.

“The government, for its part, has developed several ways to pressure journalists who dare to be overly critical of the summary methods adopted by ‘Punisher’ Duterte and his notorious ‘war on drugs’.

“After targeting the Philippines Daily Inquirer and the TV network ABS-CBN in 2017, the president and his staff have now unleashed a grotesque judicial harassment campaign against the news website Rappler and its editor, Maria Ressa” (who was recently arrested and now faces six charges).

“The persecution was accompanied by online harassment campaigns waged by pro-Duterte troll armies, which also launched cyber-attacks on alternative news websites and the site of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines in order to block them.

“In response to all these attacks, the Philippine independent media have rallied to Ressa’s call to, ‘Hold the line’.”

Pacific report cards:

The Pacific report card on media freedom from the RSF World Press Freedom Index includes:

New Zealand (7) + 1 = 10.75

“The press is free in New Zealand but its independence and pluralism are often undermined by the profit imperatives of media groups trying to cut costs. Concern was voiced about the editorial integrity of New Zealand’s leading news portal, Stuff, after the Australian entertainment giant Nine Television Network took over its owner, Fairfax Media.

“Stuff was forced to close a third of the sites it hosted and major budget cuts were imposed on the local media outlets it owns. The situation could have been even worse if the Commerce Commission had not blocked another proposed merger between Stuff and New Zealand Media and Entertainment (NZME), which owns the country’s leading daily, The New Zealand Herald…”

Australia (21) – 2 = 16.55

“Australia has good public media but the concentration of media ownership is one of the highest in the world. It became even more concentrated in July 2018, when Nine Entertainment took over the Fairfax media group. Mainly concerned with business efficiencies and cost-cutting, this new entity resembles Australia’s other media giant, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation.

“Under the very conservative Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, the government has abandoned any attempt to regulate the media market. The space left for demanding investigative journalism has also been reduced by the fact that independent investigative reporters and whistleblowers face draconian legislation …

“At the same time, the migrant detention centres run by government contractors on the islands of Manus and Nauru are in practice inaccessible to journalists and have become news and information black holes.’ [Manus is now closed with the asylum seekers living with the local community].

Samoa (22) Unchanged = 18.25

“Despite the liveliness of media groups such as Talamua Media and the Samoa Observer group, this Pacific archipelago is in the process of losing its status as a regional press freedom model. A law criminalising defamation was repealed in 2013, raising hopes that were dashed in December 2017 when Parliament restored the law under pressure from Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi, giving him licence to attack journalists who dared to criticise members of his government.

“A few months later, in early 2018, the prime minister warned Samoan media outlets not to ‘play with fire’ by being too critical in their reporting or else his government would censor their websites…”

Papua New Guinea (38) + 15 = 24.70

“Although the media enjoy a relatively benign legislative environment, their independence is clearly in danger. Journalists are exposed to intimidation, direct threats, censorship, prosecution and bribery attempts.

“The situation is all the more precarious because the media groups they work for rarely defend them when they are under attack. As a result, self-censorship is on the rise and many media outlets are regarded as Prime Minister Peter O’Neill’s mouthpieces.

“All this was particularly visible during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in the capital, Port Moresby, in November 2018, when journalists who wanted to raise sensitive issues were censored by their bosses and the government was accused of accommodating the Chinese delegation’s demands for certain journalists to be excluded although they had obtained accreditation for the events concerned…”

Tonga (45) + 6 = 24.41

“Independent media outlets have increasingly assumed a watchdog role since the first democratic elections in 2010. However, politicians have not hesitated to sue media outlets, exposing them to the risk of heavy fines. Some journalists say they are forced to censor themselves due to the threat of bankruptcy. In an effort to regulate ‘harmful’ online content, especially on social networks, the government adopted new laws in 2015, one of which provides for the creation of an internet regulatory agency with the power to block websites without reference to a judge.

“The re-election of Prime Minister Samuela ‘Akilisi Pōhiva’s [‘pro-democracy’] party in November 2017 was accompanied by growing tension between the government and journalists. This was particularly so at the state radio and TV broadcaster, the Tonga Broadcasting Commission (TBC) …”

Fiji (52) + 5 = 27.18

“The relatively pluralist and balanced coverage of the 2018 parliamentary elections – the second since the 2006 coup d’état – confirmed the Fiji media’s liveliness and spirit of resistance. But journalists are still restricted by the draconian 2010 Media Industry Development Decree, which was turned into a law in 2018, and the regulator it created, the Media Industry Development Authority, whose independence is questionable.

“Journalists who violate this law’s vaguely worded provisions face up to two years in prison. In this hostile legal environment, the acquittal of the country’s leading daily, The Fiji Times, and three of its journalists on sedition charges in May 2018 was seen as an encouraging victory for press freedom.”

Timor-Leste (84) + 11 = 29.93

“No journalist has ever been jailed in connection with their work in East Timor since this country of just 1.2 million inhabitants won independence in 2002. Articles 40 and 41 of its constitution guarantee free speech and media freedom. But various forms of pressure are used to prevent journalists from working freely, including legal proceedings designed to intimidate, police violence, and public denigration of media outlets by government officials or parliamentarians.

“The creation of a Press Council in 2015 was a step in the right direction despite the reservations expressed by the media about the way its members are elected. But the media law adopted in 2014, in defiance of the international community’s warnings, poses a permanent threat to journalists and encourages self-censorship.

“Coverage of the parliamentary elections in May 2018 nonetheless served to show the importance of the role that media pluralism can play in the construction of East Timor’s democracy.”

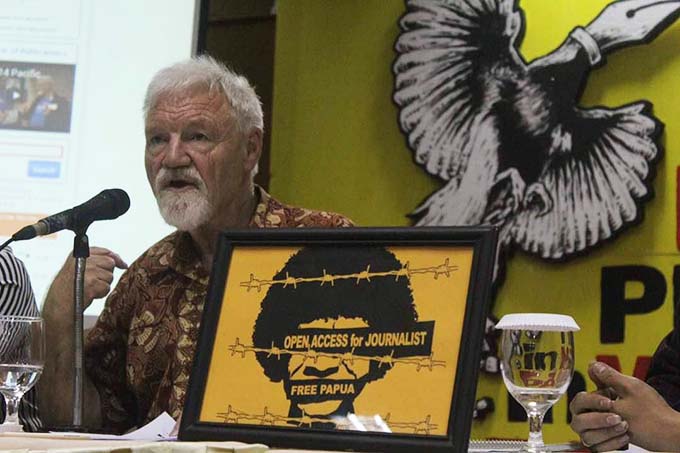

West Papua

Media freedom issues in West Papua are dire, but are partially hidden from a global gaze in the RSF Index report because they are reported on as part of Indonesia, which as a country is unchanged at 124th. The Index notes the following about President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s “broken promises”:

“President Widodo did not keep his campaign promises during his five-year term [and he now appears to have won a second term]. His presidency was marked by serious media freedom violations, including drastic restrictions on media access to West Papua (the Indonesian half of the island of New Guinea), where violence against local journalists keeps on growing.

“Foreign journalists and local fixers are liable to be arrested and prosecuted there, both those who try to document the Indonesian military’s abuses and those, such as a BBC correspondent in February 2018, who just cover humanitarian issues.

“As the Jakarta-based Alliance for Independent Journalists often reports, the military also intimidate reporters and even use violence against those who cover their abuses. Many journalists say they censor themselves because of the threat from an anti-blasphemy law and the Law on ‘Informasi dan Transaksi Elektronik’ (Electronic and Information Transactions Law).

Dr David Robie is a correspondent for Reporters Without Borders.

China wants to create a “new world media order”. Video: Reporters Without Borders