ANALYSIS: By David Robie in Auckland

The Pacific year has closed with growing tensions over sovereignty and self-determination issues and growing stress over the ravages of covid-19 pandemic in a region that was largely virus-free in 2020.

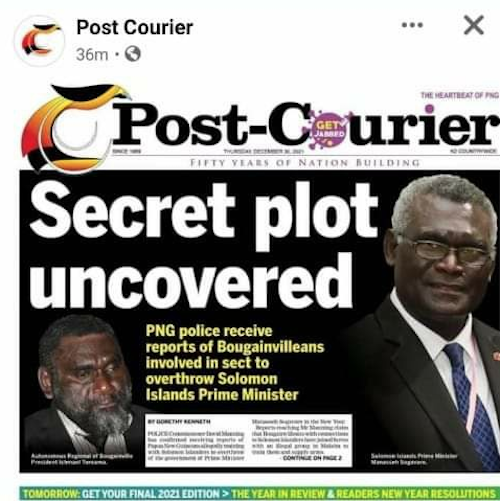

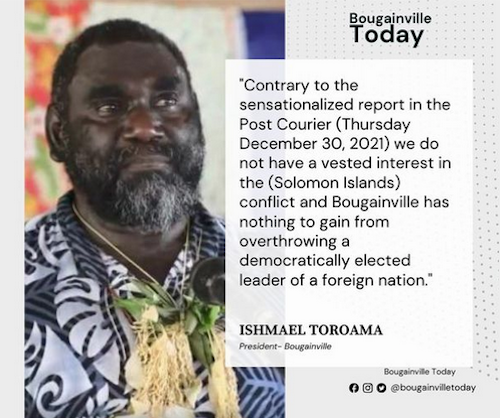

Just two days before the year 2021 wrapped up, Bougainville President Ishmael Toroama took the extraordinary statement of denying any involvement by the people or government of the autonomous region of Papua New Guinea being involved in any “secret plot” to overthrow the Manasseh Sogavare government in Solomon Islands.

Insisting that Bougainville is “neutral” in the conflict in neighbouring Solomon Islands where riots last month were fuelled by anti-Chinese hostilities, Toroama blamed one of PNG’s two daily newspapers for stirring the controversy.

- READ MORE: Flashback to Kanaky in the 1980s – ‘Blood on their Banner’

- New Caledonia referendum: France’s last pocket of settler colonialism

- Solomon Islands riots push nation into slippery slide of self-implosion

- ‘Secret plot’ uncovered

“Contrary to the sensationalised report in the Post-Courier (Thursday, December 30, 2021) we do not have a vested interest in the conflict and Bougainville has nothing to gain from overthrowing a democratically elected leader of a foreign nation,” Toroama said.

The frontpage report in the Post-Courier appeared to be a beat-up just at the time Australia was announcing a wind down of the peacekeeping role in the Solomon Islands. A multilateral Pacific force of more than 200 Australian, Fiji, New Zealand and PNG police and military have been deployed since the riots in a bid to ward off further strife.

PNG Police Commissioner David Manning confirmed to the newspaper having receiving reports of Papua New Guineans allegedly training with Solomon Islanders to overthrow the Sogavare government in the New Year.

According to the Post-Courier’s Gorethy Kenneth, reports reaching Manning had claimed that Bougainvilleans with connections to Solomon Islanders had “joined forces with an illegal group in Malaita to train them and supply arms”.

The Bougainvilleans were also accused of “leading this alleged covert operation” in an effort to cause division in Solomon Islands.

However, Foreign Affairs Minister Soroi Eoe told the newspaper there had been no official information or reports of this alleged operation. The Solomon Islands Foreign Ministry was also cool over the reports.

Warning over ‘sensationalism’

Toroama warned news media against sensationalising national security issues with its Pacific neighbours, saying the Bougainville Peace Agreement “explicitly forbids Bougainville to engage in any foreign relations so it is absurd to assume that Bougainville would jeopardise our own political aspirations by acting in defiance” of these provisions.

This is a highly sensitive time for Bougainville’s political aspirations as it negotiates a path in response the 98 percent nonbinding vote in support of independence during the 2019 referendum.

In contrast, another Melanesian territory’s self-determination aspirations received a setback in the third and final referendum on independence in Kanaky New Caledonia on December 12 where a decisive more than 96 percent voted “non”.

However, less than half (43.87 percent) of the electorate voted – far less than the “yes” vote last year – in response to the boycott called by a coalition of seven Kanak independence groups out of respect to the disproportionate number of indigenous people among the 280 who had died in the recent covid-19 outbreak.

The result was a dramatic reversal of the two previous referendums in 2018 and 2020 where there was a growing vote for independence and the flawed nature of the final plebiscite has been condemned by critics as undoing three decades of progress in decolonisation and race relations.

In 2018, only 57 percent opposed independence and this dropped to 53 percent in 2020 with every indication that the pro-independence “oui” vote would rise further for this third plebiscite in spite of the demographic odds against the indigenous Kanaks who make up just 40 percent of the territory’s population of 280,000.

The result is now likely in inflame tensions and make it difficult to negotiate a shared future with France which annexed Melanesian territory in 1853 and turned it into a penal colony for political prisoners.

Kanaky turbulence in 1980s

A turbulent period in the 1980s – known locally as “Les événements” – culminated in a farcical referendum on independence in 1987 which returned a 98 percent rejection of independence. This was boycotted by the pro-independence groups when then President François Mitterrand broke a promise that short-term French residents would not be able to vote.

The turnout was 59 percent but skewed by the demographics. The UN Special Committee on Decolonisation declined to send observers as that plebiscite did not honour the process of “decolonisation”.

A Kanak international advocate of the Confédération Nationale du Travail (CNT) trade union and USTKE member, Rock Haocas, says from Paris that the latest referendum is “a betrayal” of the past three decades of progress and jeopardises negotiations for a future statute on the future of Kanaky New Caledonia.

The pro-independence parties have refused to negotiate on the future until after the French presidential elections in April this year. A new political arrangement is due in 18 months.

In the meantime, the result is being challenged in France’s constitutional court.

“The people have made concessions,” Haocas told Asia Pacific Report, referencing the many occasions indigenous Kanaks have done so, such as:

• Concessions to the “two colours, one people” agreement with the Union Caledonian party in 1953;

• Recognition of the “victims of history” in Nainville-Les-Roches in 1983;

• The Matignon and Oudnot Agreement in 1988;

• The Nouméa Accord in 1998; and

• The opening of the electoral body (to the native).

‘Getting closer to each other’

“The period of the agreements allowed the different communities to get to know each other, to get closer to each other, to be together in schools, to work together in companies and development projects, to travel in France, the Pacific, and in other countries,” says Haocas.

“It’s also the time of the internet. Colonisation is not hidden in Kanaky anymore; it faces the world. People talk about it more easily. The demand for independence has become more explainable, and more exportable. There has been more talk of interdependence, and no longer of a strict break with France.

“But for the last referendum France banked on the fear of one with the other to preserve its own interests.”

Is this a return to the dark days of 1987 when France conducted the “sham referendum”?

“We’re not really in the same context. We are here in the framework of the Nouméa Accord with three consultations — and for which we asked for the postponement of the last one scheduled for December 12,” says Haocas.

“It was for health reasons with its cultural and societal impacts that made the campaign difficult, it was not fundamentally for political reasons.

“The French state does not discuss, does not seek consensus — it imposes, even if it means going back on its word.”

Haocas says it is now time to reflect and analyse the results of the referendum.

“The result of the ballot box speaks for itself. Note the calm in the pro-independence world. Now there are no longer three actors — the indépendantistes, the anti-independence and the state – but two, the indépendantistes and the state.”

Rock Haocas in a 2018 interview before the the three referendums on independence. Video: CNT union

Comparisons between Kanaky and Palestine

In a devastating critique of the failings of the referendum and of the sincerity of France’s about-turn in its three-decade decolonisation policy, Professor Joseph Massad, a specialist in modern Arab politics and intellectual history at Columbia University, New York, made comparisons with Israeli occupation and apartheid in Palestine.

“Its expected result was a defeat for the cause of independence. It seems that European settler-colonies remain beholden to the white colonists, not only in the larger white settler-colonies in the Americas and Oceania, but also in the smaller ones, whether in the South Pacific, Southern Africa, Palestine, or Hawai’i,” wrote Dr Massad in Middle East Eye.

“Just as Palestine is the only intact European settler-colony in the Arab world after the end of Italian settler-colonialism in Libya in the 1940s and 1950s, the end of French settler-colonialism in Morocco and Tunisia in the 1950s, and the liberation of Algeria in 1962 (some of Algeria’s French colonists left for New Caledonia), Kanaky remains the only major country subject to French settler-colonialism after the independence of most of its island neighbours.

“As with the colonised Palestinians, who have less rights than those acquired by the Kanaks in the last half century, and who remain subject to the racialised power of their colonisers, the colonised Kanaks remain subject to the racialised power of the white French colonists and their mother country.

“No wonder [President Emmanuel] Macron is as ebullient and proud as Israel’s leaders.”

West Papuan hopes elusive as violence worsens

Hopes for a new United Nations-supervised referendum for West Papua have remained elusive for the Melanesian region colonised by Indonesia in the 1960s and annexed after a sham plebiscite known euphemistically as the “Act of Free Choice” in 1969 when 1025 men and women hand-picked by the Indonesian military voted unanimously in favour of Indonesian control of their former Dutch colony.

Two years ago the United Liberation Movement of West Papua (ULMWP) was formed to step up the international diplomatic effort for Papuan self-determination and independence. However, at the same time armed resistance has grown and Indonesia has responded with a massive build up of more than 20,000 troops in the two Melanesian provinces of Papua and West Papua and an exponential increase on human rights violations and draconian measures by the Jakarta authorities.

As 2021 ended, interim West Papuan president-in-exile Benny Wenda distributed a Christmas message thanking the widespread international support – “our solidarity groups, the International Parliamentarians for West Papua, the International Lawyers for West Papua, all those across the world who continue to tirelessly support us.

“Religious leaders, NGOs, politicians, diplomats, individuals, everyone who has helped us in the Pacific, Caribbean, Africa, America, Europe, UK: thank you.”

Wenda sounded an optimistic note in his message: “Our goal is getting closer. Please help us keep up the momentum in 2022 with your prayers, your actions and your solidarity.

You are making history through your support, which will help us achieve independence.”

But Wenda was also frank about the grave situation facing West Papua, which was “getting worse and worse”.

“We continue to demand that the Indonesian government release the eight students arrested on December 1 for peacefully calling for their right to self-determination. We also demand that the military operations, which continue in Intan Jaya, Puncak, Nduga and elsewhere, cease,” he said, adding condemnation of Jakarta for using the covid-19 pandemic as an excuse to prevent the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights visiting West Papua.

New covid-19 wave hits Fiji

Fiji, which had already suffered earlier in 2021 along with Guam and French Polynesia as one of the worst hit Pacific countries hit by the covid-19 pandemic, is now in the grip of a third wave of infection with 780 active cases.

Fiji’s Health Ministry has reported one death and 309 new cases of covid-19 in the community since Christmas Day — 194 of them confirmed in the 24 hours just prior to New Year’s Eve. This is another blow to the tourism industry just at a time when it was seeking to rebuild.

Health Secretary Dr James Fong is yet to confirm whether these cases were of the delta variant or the more highly contagious omicron mutant. It may just be a resurgence of the endemic delta variant, says Dr Fong, “however we are also working on the assumption that the omicron variant is already here, and is being transmitted within the community.

“We expect that genomic sequencing results of covid-19 positive samples sent overseas will confirm this in due course.”

A DevPolicy blog article at Australian National University earlier in 2021 warned against applying Western notions of public health to the Pacific country. Communal living is widespread across squatter settlements, urban villages, and other residential areas in the Lami-Suva-Nausori containment zone.

“Household sizes are generally bigger than in Western countries, and households often include three generations. This means elderly people are more at risk as they cannot easily isolate. At the same time, identifying a ‘household’ and determining who should be in a ‘bubble’ is difficult.

“‘Stay home’ is equally difficult to define, because the concept of ‘home’ has a broader meaning in the Fijian context compared to Western societies.”

While covid pandemic crises are continuing to wreak havoc in some Pacific communities into 2022, the urgency of climate change still remains the critical issue facing the region. After the lacklustre COP26 global climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, in November, Pacific leaders — who were mostly unable to attend due to the covid lockdowns — have stepped up their global advocacy.

End of ’empty promises’ on climate

Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown appealed in a powerful article that it was time for the major nations producing global warming emissions to shelve their “empty promises” and finally deliver on climate financing.

‘As custodians of these islands, we have a moral duty to protect [them] — for today and the unborn generations of our Pacific anau. Sadly, we are unable to do that because of things beyond our control …

“Sea level rise is alarming. Our food security is at risk, and our way of life that we have known for generations is slowly disappearing. What were ‘once in a lifetime’ extreme events like category 5 cyclones, marine heatwaves and the like are becoming more severe.

“Despite our negligible contribution to global emissions, this is the price we pay. We are talking about homes, lands and precious lives; many are being displaced as we speak.”

Perhaps the most perceptive reflections of the year came from a young Kanak pro-independence and climate change student activist, Marylou Mahé. Saying that as a “decolonial feminist” she wished to put an end to “injustice and humiliation of my people”, Mahé added a message familiar to many Pacific Islanders:

“As a young Kanak woman, my voice is often silenced, but I want to remind the world that we are here, we are standing, and we are acting for our future. The state’s spoken word may die tomorrow, but our right to recognition and self-determination never will.”