New Zealand quietly celebrated 30 years of its official status as a “nuclear-free” country this week, marking the time when NZ Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act came into force on 8 June 1987. When Aotearoa/New Zealand banned nuclear warships from its ports in 1984, the country was seen as David standing up to Washington’s Goliath. But behind Prime Minister David Lange was a whole army of peace campaigners forcing him to sling his shot. David Robie traces the history of their resistance in a 1986 article for the New Internationalist – and shows how ordinary people declaring their home as a nuclear-free zone helped send a message to the superpowers.

Artist Debra Bustin sat dejectedly among the Ronald Reagan and Robert Muldoon masks, papier mâché missiles and effigies of babies in stakes, waiting. The “Nuclear Horror Show”, a dramatic piece of street theatre, was ready to roll – but there was no transport. The truck supposed to have carted the props to the start of the demonstration in the heart of Wellington had failed to turn up.

But another peace campaigner had an idea. He darted onto the nearby street and stopped the first empty truck.

But another peace campaigner had an idea. He darted onto the nearby street and stopped the first empty truck.

“Hey mate, we’ve got to get all this stuff to the big anti-nuclear rally across town.” He said. “Can you help us?”

Ten years earlier, the truck driver would have laughed at the campaigner’s cheek. However, this was September 1983, and the peace and anti-nuclear groups in Aotearoa/New Zealand had become a mass movement. The driver was delighted to help and the macabre show went ahead.

Within 10 months, conservative Prime Minister Sir Robert Muldoon had been swept out of office as David Lange and the Labour Party were catapulted into power on a nuclear-free platform, which stunned the country’s Western allies, particularly the United States.

Internationally, the move was perceived to be a bold, idealistic new step by a reformist government. Critics tried to suggest it was a result of some Machiavellian plot by the party’s “militant” left wing. In fact, it was the culmination of a policy that had first been introduced more than a decade earlier and had been reinforced at grassroots level by a highly motivated peace movement.

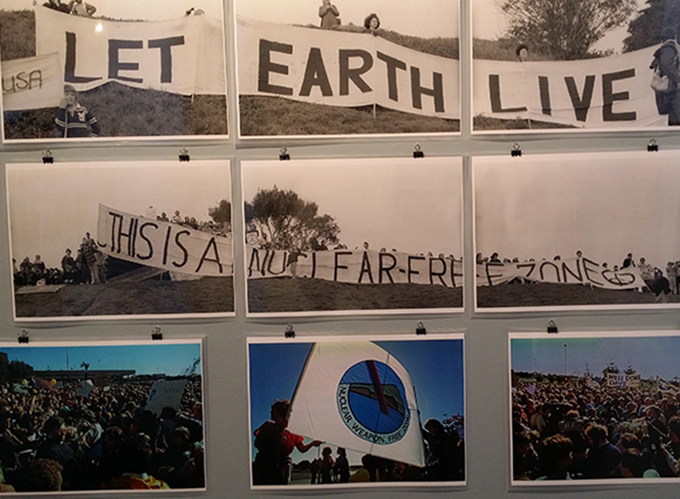

Indeed, even if the government itself had had doubts about the policy, it would have had little choice. Opinion polls showed 74 percent of people in favour of banning nuclear-armed ships, two-thirds of the country’s 3.2 million population lived in self-proclaimed “nuclear free zones” and four out of five competing political parties (including a new breakaway right-wing group) had the policy as part of their platforms.

Global peace lesson?

So what created this revolution in public opinion, and is there a lesson that the global peace movement can learn from Aotearoa’s example?

The peace movement in Aotearoa itself had humble beginnings in the 1960s with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament’s (CND) local Easter rallies being miniature clones of the huge annual Aldermaston march in the UK. However, in 1968 two things combined to create the first major rallying point: The first was the screening of Peter Watkins’ anti-nuclear TV drama The War Game (which was initially censored in the UK in 1965 and eventually screened 20 years later in 1985). The second was the US Navy’s plan to build a radio communications base called Omega, which was to aid the navigation of Polaris submarines. Sensitised to the issue by the documentary, New Zealanders were so outraged by the Omega plan that it was forced to be shelved. “Government deals NZ into War Game,” said one newspaper.

“The Watkins film brought home to New Zealanders the possibility of the country being a nuclear target,” says peace researcher Owen Wilkes. “Until then war had been a kind of sporting event. It was something that happened on the other side of the world.”

Anti-nuclear feeling contributed to Labour’s election victory under Norman Kirk in 1972. Their nuclear-free policy emerged from the fallout shelter hysteria of the early 1960s, thermonuclear tests by the superpowers and the escalating Vietnam War. In the three heady years that followed, the Kirk government shut out nuclear-armed and powered ships from New Zealand’s ports. They also dispatched frigates in support of the vulnerable flotillas of yachts that sailed to Moruroa in protest at French nuclear testing there.

But then the nuclear-free strategy was dealt a body blow. The National Party was re-elected in 1975 and Muldoon ushered in his decade of power by welcoming back nuclear ships. The Peace Squadron was formed by Rev George Armstrong in response – a loose coalition of people whose yachts, small boats and other craft mounted spectacular waterborne protests against visiting nuclear ships.

Another focus for the Peace Movement was the creation of nuclear-free zones. “We campaigned to declare your house, dog, car and boat nuclear-free,” recalls Maire Leadbeater, spokesperson of CND. It seemed small fry at the time, but later it was realised what a clever strategy it had been. It gave peace activists a manageable goal while at the same time making elected councils take a stand against nuclear facilities visiting, or being sited in their area.”

Sparked off movement

Canadian émigré Larry Ross dived into the nuclear issue in 1979 with a crusader’s zeal and an “ad man’s flair”. He made his Christchurch home headquarters of the NZ Nuclear Free Zone Committee (NZNFZC) and sparked off a movement which had remarkable success: 66 percent of the population now live in such zones declared by local authorities.

One after another local authorities declared themselves nuclear-free in the face of a barrage of letter-writing and lobbying by peace campaigners. Even larger cities became nuclear-free – councillors in the country’s largest city of Auckland considered the issue three times before deciding “yes”. Indeed, it was better, according to Larry Ross, for a council to refuse the demand at first, because this meant campaigners had to go out and involve local people, talk to them on the doorstep and get them to sign petitions.

By the 1980s, the movement was becoming more organised. Peace Movement Aotearoa (PMA) was formed, while Māori campaigners, seeking with increasing success to link “anti-nuclearism” with racism and land rights, founded the Pacific People’s Anti-Nuclear Action Committee (PPANAC).

In the wake of the social upheaval caused by the protests against apartheid during the 1981 white South Africa rugby tour, enormous energy was released which became diverted to the peace movement. In one week alone, 40,000 people protested against a warship visit. The peace movement was finally a mass one – and the Lange government’s policy was a direct result.

“Everybody thinks we have this brilliant Labour government which is dedicated to pacifism,” says Owen Wilkes. “But it isn’t, the government simply responded to public opinion, whereas in other countries where there have been similar big percentages against nuclear weapons, governments haven’t reacted.”

Why has there been such an extraordinary level of popular backing for the policy in New Zealand, a country which is so far from the centres of world tension and so unlikely to be a target in the case of any nuclear attack? One key factor has been the bitter resentment most people feel towards French nuclear testing in the South Pacific.

French persistence with the tests [they ended in 1996] in arrogant disregard of repeated protests by New Zealand, Australia and other neighbouring Pacific nations has helped keep New Zealanders acutely aware of the nuclear issue. It has also helped to provide the peace movement with credibility.

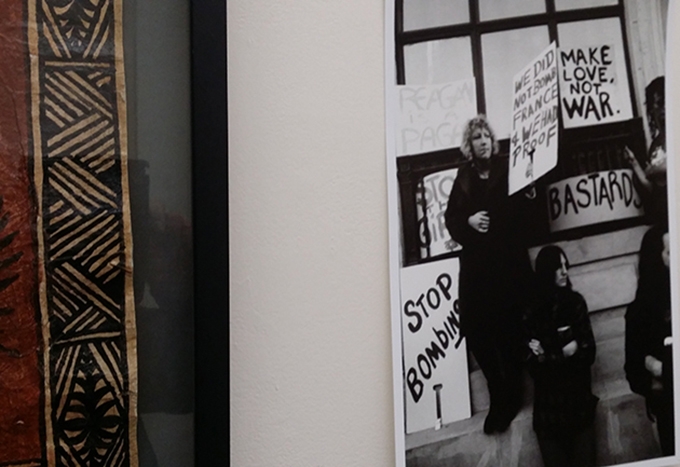

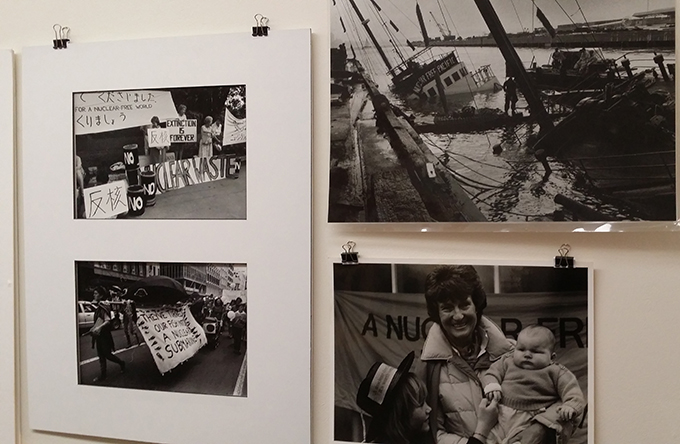

Rainbow Warrior bombing

Last year [1985], the sight of the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior, lying bombed and submerged in Auckland harbour while crew members mourned their dead photographer colleague, Fernando Pereira, became a brutal reminder to all New Zealanders of the realities of raising a voice against war. And it unquestionably strengthened the Lange government’s anti-nuclear resolve.

While Lange is portrayed internationally as a champion of the nuclear-free strategy, he is at times accused at home of backpedalling on the issue. The Peace Movement Aotearoa is also watchful for any sign that the government might soften its stance.

Last year [1985], the government tried to allow the nuclear-capable American warship Buchanan to visit and was only stymied by the strength of the peace movement. The protest ruined a carefully laid plan by the bureaucracy to open up a chink in the antinuclear strategy and prepare the ground for a compromise with the US.

Aotearoa’s policy has pushed it into an increasingly isolated position within the Western alliance. The US has applied severe pressure on the Lange government but overtly through diplomatic harassment and covertly through attempts to influence New Zealanders by CIA-funded projects involving journalists, trade unionists and opinion leaders. Britain, meanwhile, has sent envoys like Baroness Young to warn that if the NZ Nuclear-Free Zone, Disarmament and Arms Control Bill would be passed [it was enacted in June 1987] this would mean Aotearoa/NZ and the rest of the Wellington alliance would move apart.

In the face of this international pressure, Lange has become increasingly cautious. At Oxford University during the popular debate with the American Moral Majority’s Jerry Falwell in March 1985, Lange delighted his image as the nuclear-free David challenging the superpower Goliath.

But barely 15 months later, his delight in the image was not so obvious. On his first major tour of European capitals, in the wake of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the Soviet Union, he was determined to reassure Western leaders that he was no pawn of the peace movement. During a speech to the Nobel Peace Prize-winning International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, Lange almost appeared to be defending the nuclear powers in his anxiety not to be seen to be “exporting” the anti-nuclear policy.

Many people in the peace movement were disappointed that he did not use the occasion to make an emotive plea to the West for follow Aotearoa’s example. They know that they have to keep up the pressure in order to counteract the influence of the Western alliance – and support from people internationally will help them. Otherwise, a stand that has become a great source of hope to the worldwide peace movement might be endangered.

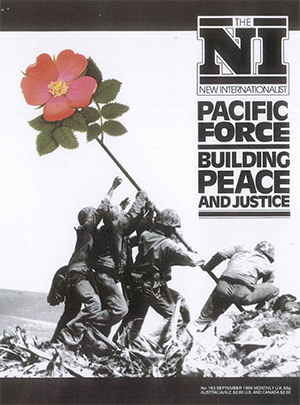

David Robie is an independent journalist based in Auckland. He specialises in Pacific affairs and is author of Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior. This republished article was commissioned for the New Internationalist and published in the September 1986 edition.

- Pacific guinea pigs

- The spirit of Kiwa

- Asia-Pacific Report image gallery

- NZ 30 years officially nuclear-free