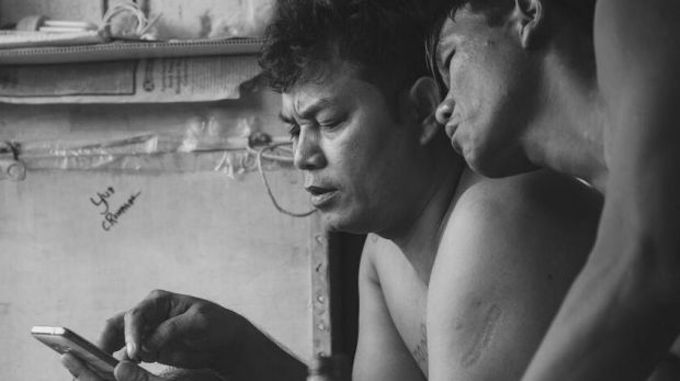

Former slaves head for home: Thousands of fishermen rescued from brutal conditions on foreign fishing boats make the journey back home, many after years at sea. As reported by Associated Press in September 2015. Video: AP on YouTube

By Jewel Topsfield of The Sydney Morning Herald in Jakarta

It’s hard to comprehend it happened in this century: human slaves trapped on fishing boats being whipped with poisonous stingray tails, having ice blocks thrown at them and being shot.

“If Americans and Europeans are eating this fish, they should remember us,” says Hlaing Min, 30, a runaway slave from Benjina, a remote fisheries weight station in eastern Indonesia’s Aru Islands.

“There must be a mountain of bones under the sea…. The bones of the people could be an island, it’s that many.”

In 2015 more than 1300 foreign fisherman from Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos were rescued from Benjina and Ambon, after an Associated Press investigation revealed the brutal conditions aboard many foreign vessels reflagged to operate in Indonesian waters.

Extraordinary images of men being kept in a cage exposed the chilling reality of 21st century slavery.

“They were trafficked from their home country, mostly by means of deception, forced to work over 20 hours per day on a boat in the middle of the sea, with little to no chance of escape,” says a report on human trafficking in the Indonesian fishing industry released this week.

Some were kept at sea for years at a time.

After the rescue, the International Organisation for Migration interviewed the fishers.

They were told of excessive work hours — 78 percent of 285 victims interviewed in depth claimed they worked between 16 and 24 hours a day, cramped conditions, meals of watery fish gruel, physical and psychological abuse and even murder.

‘Several crews died’

“While on board, I often heard the news from the boat radio that several boat crews had died, either falling to the ocean, fighting or killed by the other crews,” a Cambodian fisher says in the report.

“While I was working on the boat, I saw with my own eyes more than seven dead bodies floating in the sea.”

Witnesses testified that requesting to leave the boat could be a death sentence for some victims. Those who did might find themselves chained on the deck in the middle of the day or locked in the freezer.

“The heartrending stories of these fishers could not be left untold,” says IOM Indonesia’s chief of mission Mark Getchell.

The report says the Benjina and Ambon cases highlight the lack of adequate policing of the fishing industry and a lack of scrutiny of working conditions on ships and in fish processing plants.

Seafood caught by modern day slaves entered the global supply chain, with legitimate suppliers of fish “unaware of its provenance and the human toll behind the catch.”

“The situation in Benjina and Ambon is symptomatic of a much broader and insidious trade in people, not only in the Indonesian and Thai fishing industries, but indeed globally,” the report says.

Repatriation of enslaved fisherfmen

In 2015 the Australian government provided $2.17 million to IOM to support the daily care, repatriation and reintegration of formerly trafficked and enslaved fishermen from Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos, who had been stranded on islands in Indonesia’s Maluku province.

“This funding support has since been extended to enable IOM to provide assistance to foreign fishermen stranded in any area of Indonesia,” an Immigration Department spokesman said.

“This assistance plays a crucial role to support and protect victims of trafficking and slavery in the fishing industry by reuniting victims with their families and providing them with limited financial assistance which can help them establish an alternative livelihood.”

IOM spokesman Paul Dillon said Australia provided the lion share of the funding for its emergency response to the human trafficking crisis, which included returning more than 1000 victims to their home countries.

“This would not have been possible without the Australian government,” he said.

At the launch of the report in Jakarta this week, Indonesian Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries Susi Pudjiastuti unveiled a new government decree requiring all fisheries companies to submit a detailed human rights audit.

This was one of the report’s key recommendations to protect fishermen and port workers from abuse.

“That being said, Indonesia still has homework towards the approximately 250,000 Indonesian crews on foreign vessels operating across continents that remain unprotected,” Pudjiastuti says in a foreword to the report.

The report also called for greater diligence in recording the movement of vessels in Indonesian waters, more training on human trafficking, independent inspections of ports and vessels at sea and centres in ports where fishers could seek protection.

Jewel Topsfield is the Jakarta-based Indonesia correspondent for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald.This article was first published by the SMH and has been republished by Asia Pacific Report with permission.