By Finau Fonua, RNZ Pacific journalist

Fears are rife in Hawai’i of predatory land buying after the recent wildfires have left many locals homeless and in dire financial straits.

The wildfires incinerated the town of Lāhainā, destroying 2200 homes and businesses and leaving hundreds unaccounted for. At least 114 people are confirmed dead.

The disaster has shed light on Hawai’i’s housing crisis which has prompted many to leave the state for the US mainland.

According to Hawai’i’s Senate Housing Committee, an average of 14,000 Hawai’ians leave the state every year. The state also has one of the highest homeless rates in the country — in 2022, close to 6000 people experienced homelessness.

Hawai’i — a state notorious for high mortgage rates and rent — was already in a housing crisis before the disaster occurred. In fact, it was only last month that Hawai’i’s Governor Josh Green declared a housing emergency — announcing plans to build 50,000 homes before 2025.

“Homeowners have been reached out to by developers and realtors offering to buy their land…and this is disgusting and we just want to let people around the world to know that Lahaina is not for sale,” Maui community leader Tiare Lawrence told US media.

Lawrence accused out-of-state developers of taking advantage of the disaster, by buying up multi-generational lands from residents forced into financial desperation by the wildfires.

Lāhainā evacuee John Crewe told RNZ Pacific local inter-generational property owners were already struggling to keep up with costs before the wildfires destroyed their homes.

“People feel that they will be forced to sell out because they’re desperate, and then that will mean there is no place for them to return to,” said Crewe.

“Certain people may try to take advantage of the disaster to gain more real estate because it’s a vacation destination, people like to buy properties for vacation and that drives up the cost of everything.

“This is something that should have been addressed long ago.”

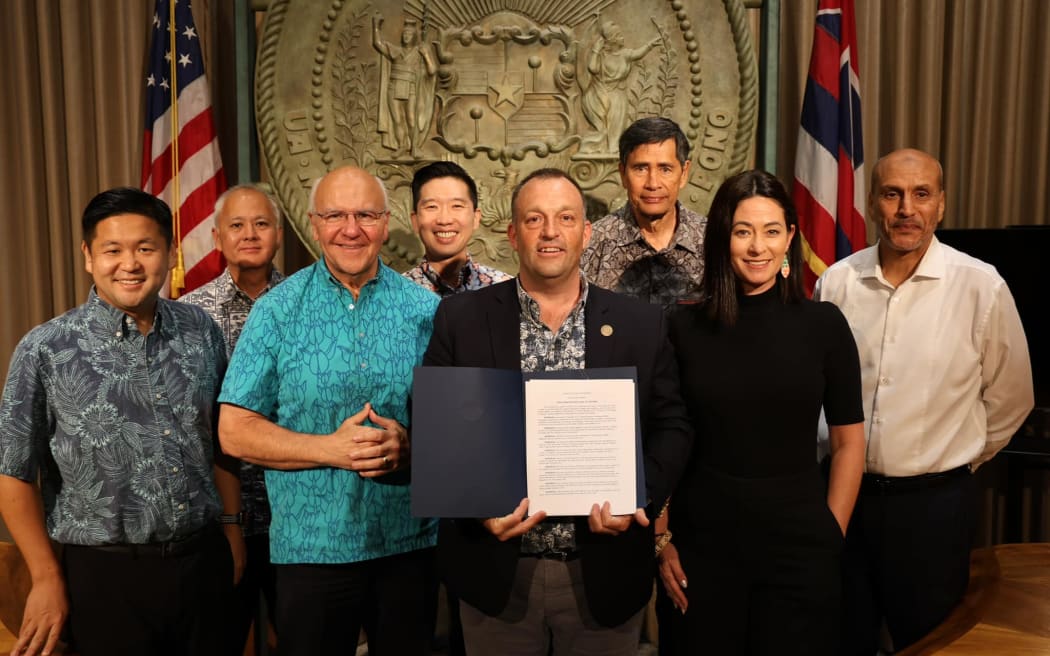

In response to the public concerns, Hawai’i’s Governor Josh Green announced he had organised attorneys to assist local landowners.

“I’ve asked my attorney to watch out for predatory practices,” Green said last week.

“We’ll also be raising incredible amount of resources to protect us financially so that none of that land falls into anyone else’s hands,” he added.

The governor even suggested the state government would look to acquire the land in devastated parts of Maui.

That comment caused a social media backlash from critics who accuse the administration of protecting the interests of lucrative hotels and tourism developers — blamed by many for making the Hawai’i’s property markets so expensive.

“Some people have taken out of context a comment I made about purchasing land — that is to protect it, to protect if for local people so that it is not stolen by people on the mainland,” said Green.

“This is not about the government getting land, this is the people’s land and the people will decide what to do with Lāhainā.”

But many remain doubtful. In the days following the disaster, thousands of Lāhainā evacuees were forced to live in gymnasiums, churches, community shelters and their cars while Maui’s many hotels and resorts remained open to tourists.

Governor Green did announce that he had arranged with hotels for more than 500 rooms to be made available for evacuees to use.

Lāhainā evacuee and Native Hawai’ian Kanani Higbee told RNZ Pacific she had no choice but to leave Hawai’i for another state where the costs of living were cheaper.

John Crewe said he prayed the community which had existed for generations in Hawaii’s historical city would remain intact.

“People might have the tendency to leave the island and go somewhere else. We should build it so that people will come back and make Lāhainā a vibrant society and not just a tourist destination,” he said.

According to Hawai’i’s Senate Housing Committee, one resident emigrates from Hawai’i every 36 minutes.

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.