SPECIAL REPORT: By Phil Thornton

The military’s brutality is a daily reality for all the people of Myanmar. As Myanmar’s army prepares to deploy and reinforce its bases with hundreds of extra troops, the country’s media workers remain exposed to Covid-19 and under extreme threat, writes Phil Thornton.

Myanmar’s military leaders used its armed forces to launch its coup and take control of the country from its elected government on 1 February 2021. In protest, millions of people took to the streets.

The military responded to these protests by sending armed soldiers and police into residential areas to arrest defiant civilians, workers, students, doctors and nurses.

In March, martial law was enforced in Yangon, snipers were used, and protesters were shot on sight.

To restrict news coverage of their crimes and to impede the organisatiojn of protests, the military ordered telecommunication companies to restrict internet and mobile phone coverage. Independent media outlets had their licences withdrawn, offices were raided and trashed.

Journalists were targeted and hunted by soldiers and police. Obscure laws were added to the penal code and used to restrict freedom of speech and expression. State-controlled media published pages of arrest warrants and photographs of the wanted, including journalists.

To avoid arrest, independent journalists went underground or sought refuge with border based ethnic armed organisations.

Myanmar journalists are well aware that being “arrested” and held in detention by the military doesn’t come with respect for their legal or human rights. The military uses a wide range of obscure laws, some dating back to colonial times, to detain, intimidate and silence its critics — academics, medics, journalists, students and workers.

95 journalists arrested

Independent website, Reporting ASEAN, recorded that, as of August 18, 95 journalists had been arrested and 42 were being held in detention.

The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) estimated by August 29 that the military has now killed at least 1026 people, arrested 7627, issued warrants for 1984 and are still holding 6025 in detention.

They want names

Those arrested are taken to interrogation centres and held indefinitely without contact with family or legal representation. Torture is used to extort names and contacts from the detained to be added to the military’s long list of those to be hunted down and suppressed into silence.

One of those names on the military’s wanted list is that of journalist Nyan Linn Htet, now in hiding, after a warrant under Section 505 (a) was issued for his arrest.

Nyan Linn Htet, managing editor of Mekong News, in an interview with the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) explains the impact of being hunted has had on both him and his family.

“If I’m arrested it means I lose everything. When we had to run and go into hiding, we lost our home and our possessions. You lose your income. Your equipment. You never feel safe when hiding. Living like this affects all of us. If the military does not find me, they will pressure and threaten my family with arrest.”

Nyan Linn Htet said he is still working despite the risk of arrest.

“Losing a journalist is a big loss for our struggle for democracy. We’re only doing our job as reporters, but our news coverage exposes the military and its abuses – this is why we’re the enemy.”

Despite the danger to him and his family, Nyan Linn Htet worries about the safety of those who helped him avoid arrest.

‘Caught in hiding’

“If I’m caught in hiding, the SAC (military-appointed State Administration Council) will persecute the people who gave me a place to live. I’m afraid they [the military] will arrest those who helped me.”

His fears are well founded.

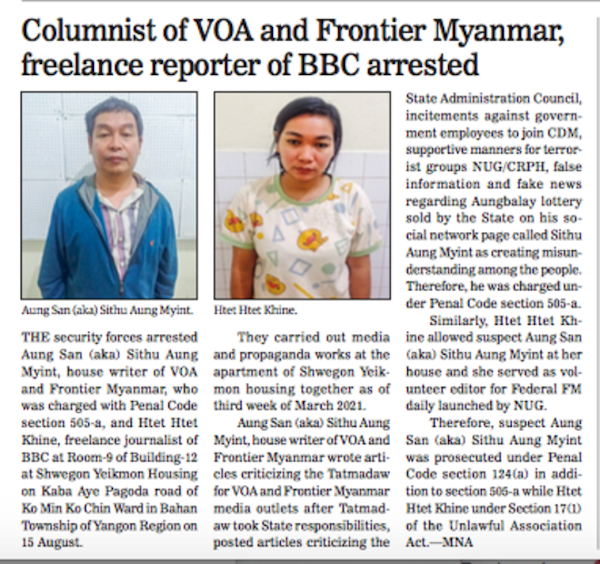

Journalist and political analyst Sithu Aung Myint was high on the military’s wanted list for his political commentary and published opposition to the coup.

On Sunday, August 15, the military raided the home of his colleague, BBC freelance producer, Htet Htet Khine, and arrested both of them.

A week later, in its Sunday, August 21, edition, the military-run newspaper, Global New Light of Myanmar, said Sithu Aung Myint had been charged with sedition, spreading “fake news” and being critical of the military coup leaders and its State Administration Council under Sections 505 (a) and 124 (a) of the Penal Code.

He could be sentenced to life in jail under Section 124 (a) of the penal code.

Htet Htet Khine was arrested for giving shelter to Sithu Aung Myint, and charged under section 17(1) of the Unlawful Association Act for working with the recently formed National Union Government’s radio station, Federal FM.

Held in interrogation centre

Friends and colleagues of Sithu Aung Myint and Htet Htet Khine told IFJ they are concerned both journalists were held at an interrogation centre for more than a week before having access to either legal help or contact with colleagues or family.

Nyan Linn Htet told IFJ he is aware his legal and human rights will not be respected if he is arrested.

“They will not let us get legal help until they’ve got what they want from us. The military amended 505 (a) of the Penal Code to prevent giving us bail. We know they will jail us even if we have legal representation.

“We know SAC is torturing journalists because of the work we do.”

Reports by local and international humanitarian groups have detailed the severe beatings — hours of maintaining stressed positions, use of sexual violence — and killing of people while held in detention.

Nyan Linn Htet said if arrested, he knows it will come with beatings. He admits that the thought of being tortured keeps him awake at night.

“They will jail me, but only after they torture me. I will not be released until I sign a statement that I will never criticise them. I’m not afraid of being arrested, but torture scares me. There are nights when I’m too afraid to sleep.”

International media drop Myanmar

He and other local journalists told the IFJ it was disappointing that international media has dropped Myanmar from its news agenda and moved on to cover other stories.

Nyan Linn Htets said despite access difficulties, the international media can use local reporters who are willing to help.

“We know the difficulties media has getting ground access to Myanmar. Covid-19 restrictions also make it impossible to legally cross borders from neighboring countries, but we are already here in the country and are capable of doing the job.”

Despite the fear of arrest and torture, he is still reporting and urged local journalists to keep doing the same.

“It’s important we use what we can to still work and report news events of interest to people. People are accessing news and information in many different ways now.”

The military, while trashing local and international laws and ignoring its constitution, is quick to use and amend laws to jail its opponents for being critical of the coup and for reporting military violence, abuse and corruption.

We have no rights

Nan Paw Gay, editor-in-chief at the Karen Information Center, says the military council has no respect for journalists or their right to publish information in the public interest.

“There is no freedom of the press. If journalists try to report news or seek information from the military’s opponents — CRPH, NUG, CDM, G-Z and PDF — the State Administration Council prosecutes them under Section 17/1 of the Illegal Association Act.

“Since the military launched its coup, sources we use have had their freedom of speech and expression made illegal and they now risk arrest for talking to us and… we can be arrested for speaking with them.

“Independent media groups have been outlawed and totally lost their right to speak freely or write about news events.”

Nan Paw Gay points out if journalists are “critical of the military, its appointed State Administration Council or its lack of a public health plan to tackle the covid-19 pandemic now ravaging the country, section 505 (a) is used to arrest journalists for spreading false news.”

Essentially torture is used to terrorise journalists, he says.

“When the military council arrests and detains journalists, the torture is both physical and psychological. Even before being detained threats are issued and then during the arrest the violence becomes real – shootings, people being kicked and dragged from homes by their hair and beaten.”

Women journalists tortured

Nan Paw Gay says women journalists are more likely to be “tortured using psychological abuse – kept in a dark room and constantly told that they will be killed tomorrow – to mess and generate fear with their thoughts. You can see the effects of the tortured on some journalists when they appear in court – shaking hands and body spasms.”

Military brutality is a daily reality for Myanmar’s people. At the time of writing, the army is preparing to deploy and reinforce its bases with hundreds of extra troops into areas of the Karen National Union-controlled territory and where anti-coup protesters, striking doctors and politicians have been offered refuge and safety.

A senior ethnic Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) soldier told the IFJ that army drones and helicopters have been surveying the area in recent months.

“We know they’ve sent munitions and large troop numbers to our area… last time we had drones flying over our area, they later attacked villages and our positions with airstrikes. They’re already fighting in our Brigade 5 and 1 and have started in 6 and 2.”

Since the military launched its coup on February 1, there has been at least 500 armed battles between the KNU and the military regime and 70,000 Karen civilians have been displaced and are hiding in makeshift camps as a direct result of these attacks.

Fighter jets have flown into Karen National Union-controlled areas 27 times and dropped at least 47 bombs, killing 14 civilians and wounding 28.

Naw K’nyaw Paw, general secretary of the Karen Women Organisation, in an interview with Karen News, said villagers displaced by the Myanmar Army attacks are now in desperate need of humanitarian aid.

‘Shoot at villagers’

“They shoot at villagers if they see them on their farms, burning down their rice barns and killing the livestock left behind. The Burma Army also arrests people when they see them and use them as human shields to protect them when attacked by Karen soldiers.”

Naw K’nyaw Paw said accessing the displaced villagers is difficult, especially during the wet season.

“The only accessible way in is on foot, supplies have to be carried through jungle. Given the restrictions due to covid-19 as well as the increasing Burma Army military operations, villagers are unable to return to their homes and they will need food, clothing and medicine, especially the young and old.”

Nan Paw Gay says the military’s strategy to muzzle the media is a familiar tactic that has been used before.

“Stop international media getting access to conflict areas, shut down independent media, hunt local journalists and when there’s no one to left to report, launch attacks in ethnic regions, displacing thousands of villagers.”

Phil Thornton is a journalist and senior adviser to the International Federation of Journalists in South East Asia. This article was first published by the IFJ Asia-Pacific blog and is republished with the author’s permission. Thornton is also a contributor to Asia Pacific Report.