By Phil Pennington, RNZ News reporter

It took seven months for the New Zealand police to set up their first team for scanning the internet after the mosque attacks – but it was almost immediately in danger of being shut down.

An internal report released under the Official Information Act (OIA) said this was despite the team already proving its worth “many times over” in countering violent extremists.

The unit still does not have dedicated funding, despite a warning last July it risked being “turned off”.

This is revealed in 170 pages of OIA documents charting police intelligence shortcomings over the last decade, from pre-2011 extending through to mid-2020, and their attempts to overhaul the national system since 2018.

These show police had no dedicated team before 2019 to scan the internet for threats – what is called an OSINT team, for “Open Source Intelligence”.

“The OSINT team was stood up quickly last year with seconded staff to ensure… [an] appropriate emphasis on this new capability,” an internal report from July 2020 said.

In fact, police began the planning at the end of 2018, then “accelerated” it after the attacks, but it took till late October for the team to start, and training began in November 2019, a police statement to RNZ last week said.

This was all well after a January 2018 official assessment of the domestic terrorism threatscap said: “Open source reporting indicates the popularity of far right ideology has risen in the West since the early 2000s”.

When the police OSINT unit was finally set up, there was no guarantee it would last.

“This team is not permanent,” the July 2020 report said.

“This has meant uncertainty for staff and our intelligence customers.”

‘Seriously compromises’

The team had no dedicated budget, and lacked trained staff.

It also was still looking for tools to “quickly capture and categorise online intelligence elements”.

“The lack of a strong OSINT capability seriously compromises our intelligence collection posture, especially in major events,” said the report last July.

This is the sort of scanning that can pick up threats on 4chan or other extremist sites.

Despite the shortcomings, the internet team’s worth had already been proven “many times over in recent months, particularly in the counterterrorism and Countering Violent Extremism space”, the report said.

Three people have faced extremist charges in the last year or so.

‘Turned off’

An April 2019 report said police would begin recruiting for OSINT analytics and other specialists in April-May 2019.

Police had lacked a tool to search the dark web – where the truly egregious chat and trades take place on the internet – so bought one.

But last July’s report said “currently we run the risk” of OSINT “being turned off unless there is a dedicated budget”.

In a statement on Friday, police told RNZ: “The OSINT team has been funded as part of the overall allocation for intelligence since it was established.

“Maintaining this capability is a NZ Police priority, and dedicated funding is being sought as part of next year’s internal funding allocation process (note, this is funding from within Police’s existing baseline).

“Additional supplementary funding was also received in the last financial year to support the work of OSINT.”

They had known they needed the team, they said.

“Prior to March 15, New Zealand Police used some OSINT tools to support open source research of publicly available information and had identified the requirement to develop a dedicated capability.

“The development of this capability was accelerated by the events of March 15.”

‘9/11 moment’

The OIA documents show the OSINT intelligence weakness was not an isolated example.

These warned police needed to avoid “a ‘9/11’ moment” – a situation where police obtain information about a threat but do not understand it due to a failure to analyse how the dots join up, as happened to CIA and FBI before the terror attacks on New York in 2001.

The solution was to have “a complete intelligence picture”.

But the July 2020 report then laid out very clearly how police did not have this:

“Recent operational examples conclude there is no current ability to access all information in a timely and accurate manner,” it said.

“Currently there is no tool that can search across police holdings [databases] when undertaking analysis of investigations.

“We are still depending on manual searches.”

‘Locked down or invisible’

“Sources are either locked down or invisible to analysts. Our intelligence picture is consequently incomplete.”

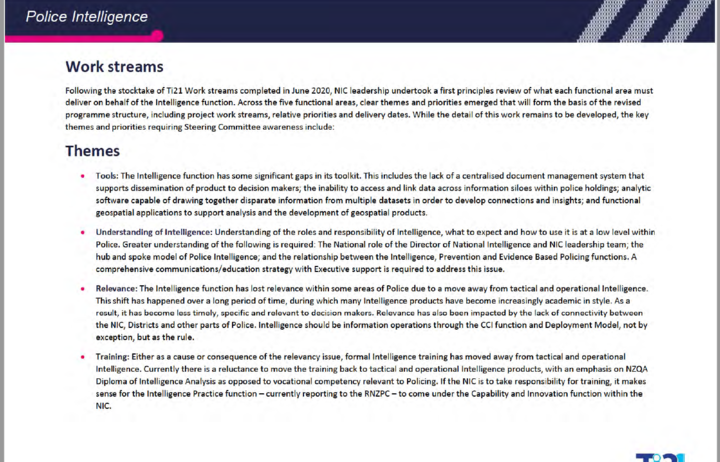

The 31-page, July 2020 report detailed the police’s ‘Transforming Intelligence’ programme, dubbed TI21, that was begun in December 2018 and meant to be complete by this December.

It indicated the right technology would not be in place – or in some cases even identified – for 6-18 months.

As things stood, “there are many single points of failure in our intelligence system”, the report said.

Threat information was broken up into silos, without a centralised document management system or powerful enough analytic and geospatial software to connect the threats.

A section of the 2020 report detailing problems within the police’s High-Risk Targeting Teams has been mostly blanked out.

The OIA documents describe what is and is not working, especially when it comes to national security and counterterrorism, but also around intelligence on gang and drug crime, family violence, combating child sex offending, and the like, at a point many months after both the mosque attacks and the beginning of the system overhaul.

The Royal Commission of Inquiry into the mosque attacks in late 2020 called police national security intelligence capabilities “degraded” – not just once but six times.

It showed weaknesses elsewhere when it came to OSINT: The Security Intelligence Service had just one fulltime officer doing Open Source Internet searching, and the Government Communications Security Bureau had few resources for this, too. It was not till June 2019 that the Government’s Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee suggested “leveraging open-source intelligence capability”.

Police, unlike SIS, did not do an internal review of how they had performed in the lead-up to March 15.

They did get a review done of how they did 48 hours after the attacks, which praised their efforts.

Tools missing

Among the key systems police have been lacking are:

- A national security portal “to search across police holdings”

- A national security person-of-interest tool

- A child sex offender management tool

- Cybercrime reporting systems – a “strategic demand” that “police intelligence is unable to effectively report on it”

Police in a statement said they had now “achieved a number of milestones”.

Key among them was introducing a National Security Portal to manage persons of interest.

Also, they now had standardised ways of improving quality and a National Intelligence Operating Model to ensure a consistent approach.

“The OSINT team, a new case management tool and “refined intelligence support to major events… has increased the capability, capacity and resilience of Police Intelligence to reduce and respond to counter-terrorism risks”.

The “Transforming Intelligence” documents refer repeatedly to having three new Target Development Centres set up in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch.

However, this was jettisoned last year, while the overhaul did stick with introducing Precision Targeting Teams in August 2018, police said.

These teams aim to target “our most prolific offenders” early on “to reduce crimes such as burglary, robbery and other violent and high-volume offending”.

Pressure on

Police are plugging the holes in national intelligence while under pressure.

The volume of leads coming in had increased “considerably” since March 2019, the July 2020 report said.

“This has put increased strain on our people to manage cases of concern.”

The intelligence weaknesses have persisted under four police commissioners since the national intelligence system was set up in 2008.

Intelligence staff have been quitting at three times the average rate in the public sector, and the documents laid out urgent plans to improve career pathways and value the likes of field officers and collections staff more.

The July 2020 report said demand on workers at the Integrated Targeting and Operations Centre was “unsustainable”.

Deep-seated cultural problems across the police were recently uncovered by RNZ’s Ben Strang, whose reporting triggered an official investigation that found 40 percent of officers had been bullied or harassed.

The Transforming Intelligence 2021 programme covers 10 areas: Intelligence Operating Model, National Security, Open Source, Child Protection Offender Register, Critical Command Information, Collections, Intelligence Systems, Performance, Training and Intelligence Support to major events.

There is a stark contrast between how the police leadership described their intelligence systems, and what other documents state.

Timeline

2003

– The Government Audit Office underscores the importance of national security planning

– Police attempt to develop a national security plan deferred due to other priorities

2006

– Police appoint first national manager of intelligence – before this it was led at district level

2008

– New national intelligence model introduced, that lasts till 2019

2011

– March: Police national security intelligence review finds many gaps and recommends a slew of fixes

2014

– Police assess rightwing extremist threat nationally, the last time this happens before the end of 2018

2015

– Sept: Police review finds 2011’s shortcomings remain, recommends changes

– Police liaison officers begin work with SIS and GCSB

2018

– August: Precision Targeting Teams begin

– Nov/Dec: Police launch Transforming Intelligence overhaul, while praising the old model

2019

– March: Mosque terrorism attacks

– April: A report ramping up the intelligence overhaul celebrates the old model’s effectiveness

– Sept: Police approve high-level operating model for intelligence

– Oct: Police set up dedicated internet scanning team for first time

– Internet scanning team identifies counterterrorism threats

– Dec: Aim to set up professional development structure to reduce Intelligence staff attrition by 15 percent

2020

– National Intelligence Centre leadership team appointed

– Feb: Intelligence training plan in place; national workshops

– July: Stocktake of Intelligence overhaul finds many gaps

– Dec 2020-Dec 2021: Aim to identify new intelligence gathering and analysing tech, including a police-wide system

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.