ANALYSIS: By Malou Mangahas in Manila

Eight years ago on 23 November 2009, 32 journalists were among the 58 who were killed in what is now known as the Maguindanao Massacre, until then the worst and most tragic incident of media lives lost in a single day.

Multiple murder charges have been filed against more than 100 people for the incident but to this day, the presentation of defence witnesses has not finished, and about 80 other respondents remain at large.

Indeed, acute assaults on journalists and media freedom should not pass with impunity.

Today, as the nation marks the 8th anniversary of the Maguindanao massacre, this composite report of the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, and the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, illustrates why the press in the Philippines would do well to understand the severity of the challenges it faces under the Duterte administration — a situation of benign and acute impunity, and fettered flow of information.

While we remain a free community in law and theory, and blessed with a Constitution that enshrines protection, a tectonic shift has moved the ground and the foundation of the practice of journalism in the last 16 months.

The press in the Philippines has been described to be among the freest in Asia if not in the world, robust, almost rambunctious in its practice. But in the first 16 months of the Duterte administration, its status and practice have been diminished, shaken down by supporters and trolls of the President who would not tolerate critical coverage.

No less than the President has struck at the heart of the institution with threats of action against major news organisations. He has cursed journalists in public for raising testy questions about his health, catcalled a female reporter, and averred without serving proof that journalists are killed because they are corrupt.

Toxic mix

This toxic mix — over-reaching executive power, the threat of violence and public censure, and divided and fettered newsrooms — has left the flow of information unfree, convoluted, and constrained under the Duterte presidency.

To be sure, the administration has taken steps early in its rule to address the attacks and threats, and a string of unsolved murders of Filipino journalists from earlier years.

Duterte signed Administrative Order No. 1, Creating The Presidential Task Force On Violations Of The Right To Life, Liberty And Security Of The Members Of The Media (PTFoMS), on 11 October 2016. But the agency that is also called PTFoMS lacks resources and personnel to have genuine impact.

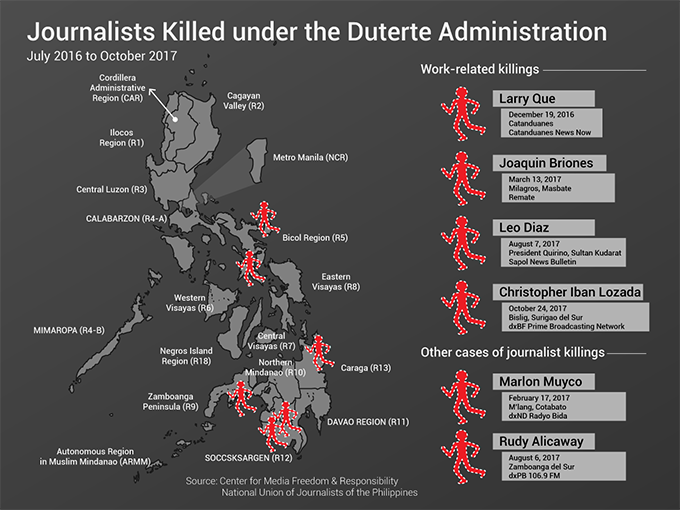

The cases of assaults on the media under the Duterte presidency turned bad in succeeding months, however. From May to October this year, the number of casualties among members of the press began to rise again.

In the first 16 months of the Duterte presidency:

- Six journalists have been killed, including the three that had been listed by the Task Force;

- Eight have survived slay attempts and received death threats;

- Three libel cases have been filed, even as a libel case filed in 2015 has led to the arrest of the accused. Other libel cases filed in previous years ended in an acquittal and two convictions; and

- Six major cases of verbal and online threats from local officials or pro-Duterte bloggers have been reported.

These acute and direct attempts to harass and muzzle journalists and media freedom have unfolded alongside more benign but equally grave threats to the practice of journalism and the free flow of information in the Philippines today. For instance:

- Access to information remains problematic for journalists and media agencies covering the war on drugs. Getting information, especially on sensitive and controversial cases, remains constrained;

- Against their will, media personnel are sometimes compelled by police officers to sign on as witnesses in police anti-drug operations, supposedly as mandated by the law;

- Newsroom protection for the safety of journalists covering the war on drugs remains lacking; and

- Psychological trauma overwhelms media coverage teams assigned to the war on drugs on account of their repeated first-hand exposure to revolting images of the dead, the maimed, the enraged, as well as the tremendous grief of the family members of the victims.

Malou Mangahas is executive director of the Philippine Centre for Investigative Journalism(PCIJ). She will be in Auckland next week to address the Pacific Media Centre’s 10th Anniversary seminar on Thursday.