Smoke billows from Vanuatu’s Manaro Voui volcano on Ambae island. Video: The Guardian

ANALYSIS: By Chris Firth

If you turned on the television this week, you may have seen coverage of the potentially imminent eruption of Mount Agung volcano in Bali.

However, Mt Agung is not the only volcano in the region behaving badly. An evacuation of 11,000 residents in Vanuatu has been announced thanks to increasing levels of activity at Ambae volcano.

READ MORE: Bali’s Mount Agung threatens to erupt for the first time in more than 50 years

While both Ambae and Agung pose significant threats to local populations, they represent very different types of volcanoes.

In fact, the unique features of the Ambae volcano mean it presents immediate danger.

What’s special about the Ambae volcano?

Ambae does not fit the stereotypical image of a volcano. Rather than being a steep-sided cone, it forms a low-angled mountain, reminiscent of shield lying flat on the earth.

Instead of having a vertiginous vent filled by a lava lake (like its southern neighbour Ambrym), the summit contains a shallow depression featuring several water-filled lakes.

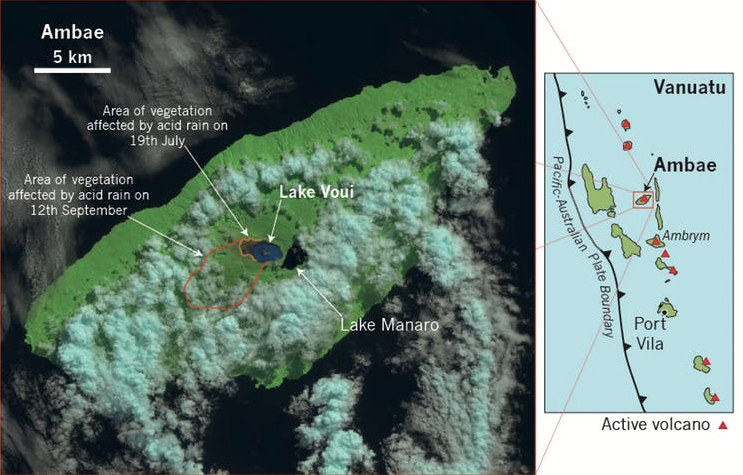

The largest of these, Lake Voui, is the current focus of volcanic activity, and looks unlike any lake you have seen before.

Volcanic gasses, including sulfur, chlorine and carbon dioxide, are discharged into the base of the lake. Not only do these make the lake highly acidic, but they typically give it a vibrant turquoise colour.

When the volcano last erupted in 2005, ash and lava built a cone in the centre of the lake, which eventually reached a height of around 50 metres above the lake surface.

As this happened, changing degrees of interaction between the lava, volcanic gases and the lake water caused fluctuations in its chemistry. This in turn changed the colour, which went from turquoise to battleship grey and then finally to a deep mahogany shade of red.

Since then, the volcano has continued to emit huge volumes of gas, which have caused issues for local inhabitants over recent years, as they can lead to acid rain.

Acid rain can kill plants. This is a major issue on Ambae, as much of the population lives on staple crops such as banana and taro. These plants have large leaves that are particularly susceptible to acid rain.

Over the past few weeks, gas emissions from Ambae have increased. Ash began to accompany the gas emissions around mid-September, suggesting that magma had reached the surface.

These changes in volcanic activity have repeatedly led the Vanuatu Meteorology and Geohazards Department to increase the alert level for the volcano.

Satellite monitoring indicates that volcanic activity is continuing to escalate. Recent observations by New Zealand Air Force pilots noted lava blasting out of a crater in the centre of Lake Voui.

Is this part of the Ring of Fire?

Both Bali’s Agung and Ambae sit on the Pacific’s “ring of fire”, and the same tectonic forces are responsible for both volcanoes. However, closer links between the two volcanoes are very unlikely.

On any given day, there are generally 20-30 volcanoes erupting around the world (although normally these eruptions are on a smaller scale and are away from large populations, so they do not make the news).

So how might the eruption at Ambae differ from Agung? The crater lake on Ambae offers particular hazards that might not be encountered elsewhere.

The first of these involves interaction between erupting lava and the lake water itself. The heat of the lava, which is likely to be 1000-1100℃, will rapidly turn lake water into steam, like dipping a hot frying pan into a sink of dishwater.

READ MORE: Vanuatu not ready for disasters, says PM

This scaled-up kitchen scenario can increase how explosive the eruption is, giving blasts from the volcano additional power. This may cause projectiles like lava bombs to go further, while also increasing the amount of ash produced.

A potentially more serious hazard may involve overflowing of the crater lake itself. If the eruption begins to displace water from the lake, it might trigger volcanic mudslides known as “lahars”, which would race down the volcano’s flanks, with the potential to inundate villages and gardens.

Local stories suggest villages on the island’s south coast were affected by lahars during the late 19th century, with significant loss of life.

Finally, there is a threat that activity may not be restricted to the volcano’s summit. The geological record indicates that magma has moved through fissures in the volcano’s flanks during previous eruptions, travelling laterally up to 20km from the centre of the volcano before erupting.

This means that rather than emerging on the sparsely inhabited summit of the volcano, lava may well erupt along the more densely populated coast. Such a scenario occurred in 1913 on the neighbouring volcano, Ambrym, where 21 people died.

The evacuation of the Ambae’s population will prevent such loss of life if this were to occur again.

Dr Chris Firth is a lecturer in geology at Macquarie University in Sydney. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence.