Pacific Media Watch editor Kendall Hutt’s video on the nuclear free law campaign.

Off The Wall: with Padre James Bhagwan in Suva

As we conclude the month of June 2017, it would be remiss of me not to draw our attention to our neighbour New Zealand, which yesterday broke a 14-year drought on the water to convincingly win the oldest trophy in international sport — the America’s Cup.

However, the emergence of New Zealand as a yachting superpower is not the only reason it makes history this month. This year marks the 30th anniversary of Aotearoa becoming a “nuclear-free” country when the NZ Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act came into force on 8 June 1987, the day we globally mark as World Ocean’s Day.

Professor David Robie, director of the Pacific Media Centre, believes activist movements in New Zealand through the 1980s helped spark the change needed for the country’s nuclear-free stance in the Pacific.

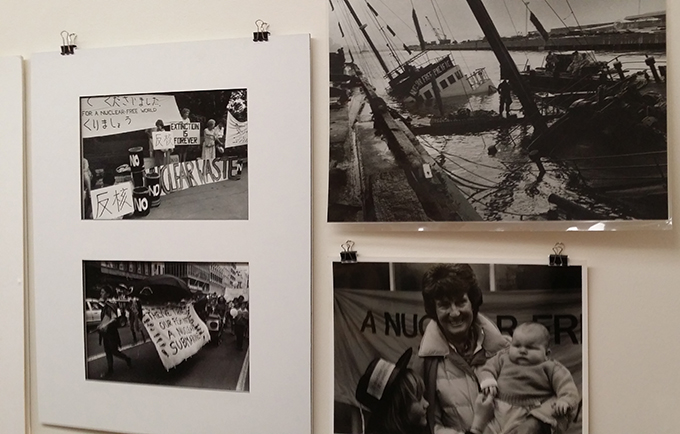

“What pushed NZ in the direction it did with the nuclear-free approach was the masses of activism, of just ordinary people, people getting out on their boats on Auckland harbour for example.”

Speaking at an event, “Celebrating 30 years of Nuclear-Free Aotearoa/New Zealand 1987/2017,” organised by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) — Aotearoa, Dr Robie said the process to achieve the nuclear-free stand was a David and Goliath struggle to make NZ nuclear-free against the US and global pressure.

“The real ‘David’ were the ordinary people of New Zealand who exerted extraordinary pressure on the government to deliver. The barrages of letters from citizens, constant lobbying by peace campaigners, local councils … declaring themselves nuclear-free, the door-knocking petitioners and, of course, the spectacular protests.”

Pacific ‘ahead of the game’

The author of Eyes of Fire: the Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior (1986, 2005 and 2015), and Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face: Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific (2014) also reflected on the impact of what happened in NZ on the Pacific, acknowledging some small Pacific countries and communities who were “actually ahead of the game”:

- 1979 — The Republic of Palau (Belau) adopted a nuclear-free Constitution and was forced by the US to hold a further 10 referenda in attempts to undermine the document. The “father” of the Constitution, President Haruo Remeliik, was assassinated on June 30, 1985. In the end, the people of Belau were ironically forced to vote to drop their nuclear-free status for “economic survival” a month after New Zealand’s Bill became law;

- 1980 — The newly independent nation of Vanuatu, formerly the New Hebrides, also adopted a nuclear-free Constitution and banned nuclear ships from its territorial waters. The country was led by the inspirational Father Walter Lini, who linked nuclear weapons with colonialism;

- 1983 — Tahiti’s airport suburb of Fa’aa led by mayor Oscar Temaru, who later became president of French-occupied Polynesia several times, declared itself nuclear-free; and

- 1987 — The first Fiji Labour Party government led by Dr Timoci Bavadra also planned to bring in a nuclear-free law but was deposed at gunpoint in the first military coup of Lieutenant-Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka in May that year.

Why is this 30th anniversary of a nuclear-free NZ and the Pacific struggle to also be nuclear-free important today?

According to ICAN (International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons), nine countries together possess around 15,000 nuclear weapons. The US and Russia maintain roughly 1800 of their nuclear weapons on high-alert status — ready to be launched within minutes of a warning.

Many times more powerful

Most are many times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in 1945. A single nuclear warhead detonated on a large city could kill millions of people with the effects persisting for decades.

The failure of the nuclear powers to disarm has heightened the risk of other countries acquiring nuclear weapons. The only guarantee against the spread and use of nuclear weapons is to eliminate them without delay. Although the leaders of some nuclear-armed nations have expressed their vision for a nuclear-weapon-free world, they have failed to develop any detailed plans to eliminate their arsenals and are modernising them.

Someone, who participated in the early Pacific-wide protest movement against nuclear weapons testing and militarisation of the Pacific region, Fiji-based Vanessa Griffen says: “In the Pacific, we have collectively experienced the known and unknown consequences of nuclear weapons use, the push by non-nuclear states for a ban on nuclear weapons is the only sensible, humane and responsible course of action to take.

“Nuclear weapons states should be regarded, collectively, as lawless and flouting international humanitarian standards.”

Griffen became aware of the environmental and genetic impacts of radioactivity from French nuclear weapons testing in French Polynesia as a student at the University of the South Pacific. She joined the anti-nuclear movement ATOM (Against Testing on Moruroa) and helped form the early Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP) network.

Concurrently, she was part of the Pacific women’s movement which was always against nuclear weapons testing and for a peaceful Pacific.

She has been a representative of FemLINKPacific, a partner member of ICAN and the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC).

Plea to use statehood

“Pacific Island states, with an unusually high experiential qualification for speaking up for nuclear disarmament, are a significant number in the United Nations and should use their statehood collectively and effectively on this global issue of nuclear disarmament,” she said.

From 1946 to 1958, the US conducted 67 atomic and hydrogen bomb tests at Bikini and Enewetak atolls in the Marshall Islands, accounting for 32 percent of all US atmospheric tests. In the 1960s, there were 25 further US tests at Christmas (Kiritimati) Island and nine at Johnston (Kalama) Atoll.

The UK tested nuclear weapons in Australia and its Pacific colonies in the 1950s. Starting in 1952, there were 12 atmospheric tests at the Monte Bello Islands, Maralinga and Emu Field in Australia (1952-57).

There were also more than 600 “minor” trials, such as the testing of bomb components and the burning of plutonium, uranium and other nuclear materials, conducted at Maralinga.

Under “Operation Grapple”, the British Government conducted another nine atomic and hydrogen bomb tests at Kiritimati and Malden islands in the central Pacific from 1957 to 1958.

After conducting four atmospheric tests at Reggane (1960-61) and 13 underground tests at In Eker (1961-6) in the Sahara desert of Algeria, France established its Pacific nuclear test centre in French Polynesia.

For 30 years between 1966 and 1996, France conducted 193 atmospheric and underground nuclear tests at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls.

Fragile ecology

Their impact on the fragile ecology of the region and the health and mental wellbeing of its peoples has been profound and long-lasting. Pacific Islanders continue to experience epidemics of cancers, chronic diseases and congenital abnormalities as a result of the radioactive fallout that blanketed their homes and the vast Pacific Ocean, upon which they depend for their livelihoods.

As you read this, the United Nations is convening negotiations in 2017 on “a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading towards their total elimination”. This new international agreement will place nuclear weapons on the same legal footing as other weapons of mass destruction, which have long been outlawed.

The negotiations began at UN headquarters in New York for one week in March and will continue from June 15 to July 7, with governments, international organisations and civil society participating.

Despite being the most destructive, inhumane weapons ever invented, nuclear weapons are the only “weapons of mass destruction” that are not yet banned under international law. (Chemical and biological weapons are both banned internationally.)

In December 2016, the UN General Assembly took action to address this crucial gap, voting to begin negotiations in 2017 for a treaty to ban nuclear weapons.

Pacific Island governments have joined the historic talks at the United Nations that should result in an international treaty that bans nuclear weapons as the second, and possibly final round of negotiations aims to have a final text on a treaty adopted in early July.

Reverend James Bhagwan is an ordained Methodist minister and a citizen journalist. He contributes the regular “Off The Wall” column to The Fiji Times and this article is republished with permission. The opinions expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Methodist Church in Fiji or the newspaper.