Israeli settlers’ aggressive takeover of Palestinian homes in Jerusalem is part of a decades-long struggle, writes

أيمن حسونة about Israel’s system of apartheid leading up to the current crisis, translated by Yasmeen Omera.

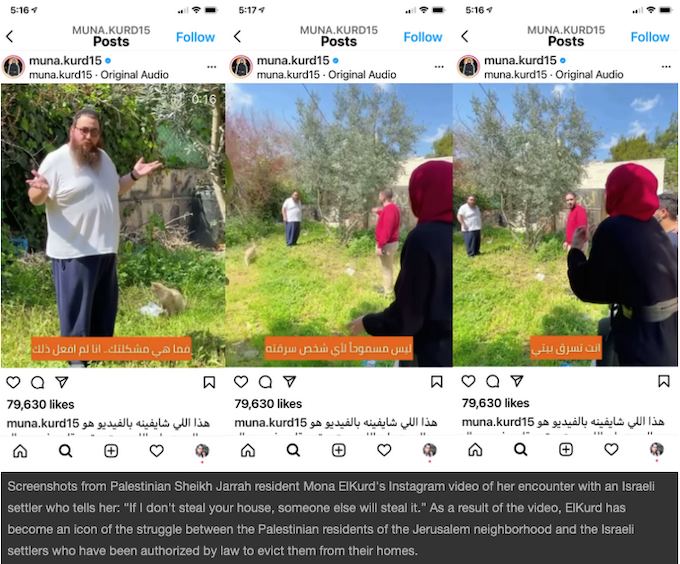

“If I don’t steal your house, someone else will.”

This is how an Israeli settler called “Yakob” responded to the Jerusalemite journalist Muna El Kurd when she asked him to leave the garden of her home in Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood.

The video of the exchange Kurd posted on her Instagram page was shared on many news pages and sites, going viral and becoming iconic of the oppression her family—and the neighbourhood—currently faces.

The ongoing apartheid in Jerusalem.

“Even if i get out of the house, it won’t be returned to u” pic.twitter.com/5sELdmClH5

— Abed🐺 #SaveSheikhJarrah (@Abd_HajYahia) May 1, 2021

- WATCH: #Palestine: Videos of violence, images of death on social media – Al Jazeera’s Listening Post

Since El Kurd posted her video, tensions in the occupied Palestinian territories have flared up to the worst level in years. The blockaded enclave of Gaza has been pounded by Israeli airstrikes as Muslims marked the end of Ramadan, their holy month of fasting.

So far, at least 212 people, including 61 children, have been killed in Gaza so far since the latest violence began more than a week ago. Some 1500 Palestinians were also wounded.

Ten Israelis, including two children, have been killed as Hamas, which governs Gaza, fired hundreds of rockets on Israeli-occupied territories, in response to earlier Israeli provocation.

Meanwhile, hundreds of Jerusalemites have been wounded by occupation forces who have clamped down on protesters and worshippers in the past weeks.

The tensions in Jerusalem coincided with the start of Ramadan on May 13. Occupation Israeli forces set up barricades to block Jerusalemites from accessing the area of Bab Al-Amud, preventing them from observing a longtime ritual of casual gatherings in that part of the Old City.

This resulted in protests—which have come to be called the “Bab Al Amud Uprising”— which eventually displaced the barriers and obstacles erected by the Occupation forces.

This was followed by Israeli forces’ storming of Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem’s Old City, one of Islam’s holiest sites, firing tear gas and stun grenades and wounding many, and coincided with Israeli settlers appropriating the homes of Palestinians in Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood, citing Israeli court verdicts.

Sheikh Jarrah: a decades-old struggle

The struggle over Sheikh Jarrah dates back to 1948, when representatives of the then-nascent state of Israel tried to storm the neighborhood, displace its people and destroy their homes. They were prevented from doing so by the British forces, which were protecting the city of Jerusalem at the time.

Fast-forward to the Six-Day War—also known as the June 1967 War—when Israeli forces occupied the West Bank, including Jerusalem and its environs.

Since then, consecutive Israeli governments have sought to displace the Palestinian population from the city of Jerusalem to shift its demographics to a Jewish majority, in line with efforts to position the city as Israel’s capital and mobilise countries to relocate their embassies there.

This despite Palestine’s United Nations-backed claim to at least part of the city as its capital.

The neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah, located to the north of Jerusalem’s Old City, contains one of the main arteries linking the concentration of the city’s Jewish population in the city to Hebrew University. Seizing control of the neighbourhood would bring the entire eastern side of Jerusalem under Israel’s authority.

The expulsion of Palestinians goes back to the period 1948-1967, when Jerusalem was under Jordanian control. In 1956, the Jordanian authorities, in cooperation with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), constructed housing for 28 refugee families in Sheikh Jarrah. The Jordanian Ministry of Construction and Development provided the land, with the proviso that construction took place through the UNRWA and that ownership of the homes would be transferred to their residents three years after the completion of construction. But this did not happen until 1967, when Jordan lost control of the West Bank.

أيام قليلة تفصلنا عن قرار محكمة الاحتلال بإخلاء حي #الشيخ_جراح او تأجيله.

أكثر من 500 فلسطيني موزعين على 28 عائلة يواجهون شبح نكبة جديدة وتهجير قسري.

لنعلي أصواتنا دعماّ وإسنادا لأهلنا في الحي المقدسي. #انقذوا_حي_الشيخ_جراح pic.twitter.com/XjDc6pL541— فلسطين27 (@Pal_27KM) April 30, 2021

A few days separate us from the occupation court’s decision to evacuate the Sheikh Jarrah’s neighborhood #الشيخ_جراح or postpone it. More than 500 Palestinians over 28 families face the spectre of a new catastrophe and forced displacement. Let’s raise our voices to support our people in the Jerusalem’s neighborhood. #انقذوا_حي_الشيخ_جراح pic.twitter.com/XjDc6pL541 — فلسطين27 (@Pal_27KM) April 30, 2021

With Jerusalem under Israeli control, Israeli settler organizations began occupying houses whose residents happened to be absent at the time, even if temporarily. The Shatti family, for example, lost their house while they were away on a visit to Kuwait in 1967.

In 1972, two Israeli societies comprising Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews went to the Israeli Land Registry Department claiming ownership of the area of Karm Al-Jaouni in Sheikh Jarrah. The claim was based on a purchase document allegedly dating from the Ottoman period. The societies were granted ownership of the land.

Between 1974-1975, the two societies then filed a lawsuit in an attempt to force four families to evacuate their homes. The Israeli court dismissed the cases because the residents were tenants protected by law.

But the lawsuits resumed again in 1982, this time against 23 families, 17 of whom retained an Israeli lawyer, Tosya Cohen. In 1991, however, Cohen shocked his clients by concluding a deal with the two settler societies, recognising their ownership of the land. Cohen’s recognition created a legal precedent that paved the way for the two societies to strip Palestinians such as the Hanoun and Ghawi families of their homes.

An initial court decision directed these two families to pay rent to the plaintiffs, and although they complied, they were expelled in 2002. In 2003, the two societies sold their share in the land to an investment company. The change in ownership allowed the Hanoun and Ghawi families to appeal their expulsion, enabling them to return to their homes until the case was adjudicated.

Mona ElKurd’s family has been the target of lawsuits since the beginning of the 1990s. After numerous rulings, the last of which was in 2009, Israeli settlers were granted the right to appropriate the ElKurd’s house. Since that time, ElKurd family has been sharing their home with the settlers who appropriated it, leaving them with only 50 metres to live in.

More recently, in October 2020, El Kurd, Al Qasim, Al Jauni and Al Skafi families received evacuations notifications from the Israeli Magistrate’s Court. In September, three other families—Hammad, Dajani, and Al Dawoudi—received similar notifications, bringing the total of people facing threats of eviction from their homes to 55. These decisions were suspended until February 2021, during which an evacuation order was issued to be carried out by Thursday, May 6, 2021, resulting in the current escalation.

Sheikh Jarrah residents ‘can’t breathe’

As tensions brewed, Palestinians took to social media to speak about the oppression they’re facing.

Bentzi Gopstein (Lehava), one of the “Death To Arabs” march organizers, is coming to Sheikh Jarrah tonight at 8:30 pm. #SaveSheikhJarrah from colonial violence. https://t.co/ov5rqBjDVE

— mohammed el-kurd (@m7mdkurd) May 6, 2021

The phrase “I can’t breathe”—the last words uttered by George Floyd as he was killed by police last year in Minnesota—is trending on social media among Palestinian users and sympathisers, as Israeli occupation forces violently cracked down on those expressing solidarity with the evicted residents of Sheikh Jarrah.

“I cant breath” he said.

The apartheid never stops. pic.twitter.com/jnQXZr6W5M

Another Twitter user, Kawther, wrote:

— Abed🐺 #SaveSheikhJarrah (@Abd_HajYahia) May 4, 2021

The same violence but no one speak . 💔💔#انقذوا_حي_الشيخ_جراح pic.twitter.com/N1HYD5M4iF

— kawther slama (@KawtherSlama) May 6, 2021

In a gesture of solidarity with residents of Sheikh Jarrah, Jerusalemites broke their fast every day of Ramadan in front of houses whose residents were being made to evacuate. This prompted Itamar Ben Ghafir, a member of Israel’s Knesset and leader of the Israeli far-right party Otzma Yehudit, to participate in a gathering in the district on May 6, the day set by the court to evacuate these houses, where he made the provocative announcement that he would relocate his office to Sheikh Jarrah to confront the “Arab extremists”.

When a crowd of Palestinians gathered to express their rejection of the parliamentarian’s incitements, a settler pepper-sprayed the Palestinians, an act documented in many video clips.

Israeli settlers spray pepper gas at Palestinian youths in Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood.

#SaveSheikhJarrah #انقذو_حي_الشيخ_جراح pic.twitter.com/baiP9UeuH0— Huda Fadil 🇵🇸 #Gaza (@HudaFadil2) May 6, 2021

This led to a clash between the two sides, involving the throwing of chairs and stones.

مستوطن يرش الشباب بغاز الفلفل وقت الافطار، والشباب ما قصرو معاه 😀.#انقذو_حي_الشيخ_جراح #SaveSheikhJarrah pic.twitter.com/pmNArc0bFy

— شجاعية (@shejae3a) May 6, 2021

A settler sprays the guys with pepper spray, and the guys didn’t disappoint #انقذو_حي_الشيخ_جراح

#SaveSheikhJarrah pic.twitter.com/pmNArc0bFy

— شجاعية (@shejae3a) May 6, 2021

Israeli occupation forces intervened and arrested several Palestinians.

The Palestinian Ministry of Foreign Affairs presented the official documents containing details of the displacement operations carried out by Israel to the International Criminal Court on May 5, but the confrontations on the ground are not expected to abate.

On May 10, an Israeli court postponed a session scheduled that day to decide the fate of Palestinian residents of Sheikh Jarrah. Announcing that the date of the upcoming session would be set within 30 days, the court permitted families facing eviction to remain in their houses until the session is held.

Muna El Kurd, whose Instagram video has turned her into an emblem of the struggle of Sheikh Jarrah’s residents, wrote:

We should not stop. Freezing [the decision] is not cancelling it.. The movement of Sheikh Jarrah is a popular and global movement against displacement and colonization in Jerusalem and all of Palestine. We must raise our voices, and intensify efforts through our presence and solidarity in Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood, and intensify our voice on social media platforms, because the violence of the colonial occupation is prevalent and its outbreak in our cities has not been frozen.

أيمن حسونة and Yasmeen Omera are Global Voices contributors.Republished with permission from Global Voices under a Creative Commons licence.