David Robie, concluding his three-part series about Iran, profiles an extraordinary pair of Tehran brothers who have been pioneering global research adventurers.

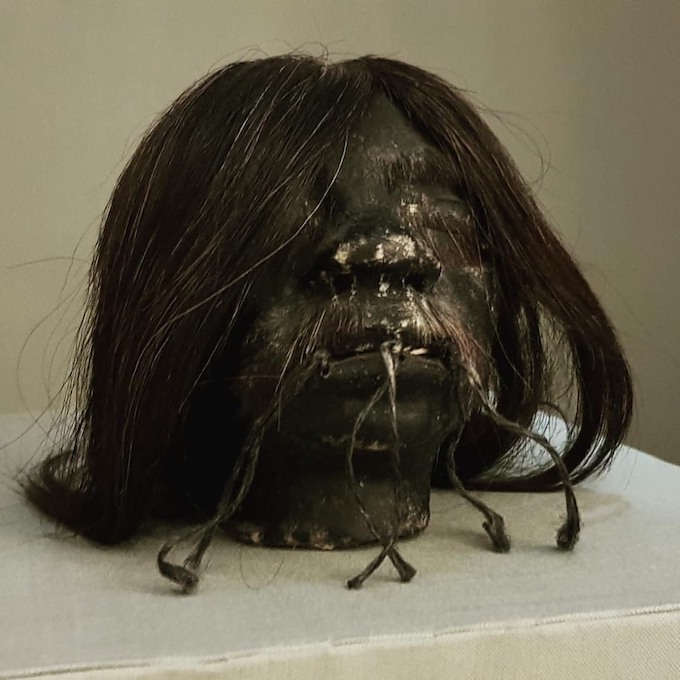

They have been dubbed the “Persian Indiana Joneses”. Their adventures are fabled and hair-raising, as shown by a Jivaro shrunken human head and relics from curious rituals on display from almost 70 years ago.

But the Omidvar brothers from Iran were no gung-ho adventurers, merely gate-crashing hidden tribal and indigenous communities around the world. They were also no elitists.

They were courageous research adventurers and their motto was “all different – all relative”.

READ MORE: Around the world in 800 days

A 2015 Iranian Press TV channel documentary about the Omidvar brothers.

Today their exploits and treasured artefacts are kept alive in the fascinating Omidvar Brothers Museum, housed in a restored coach gatehouse near the Green Palace in the Pahlavi era Sa’ad Abad forest complex in North Tehran.

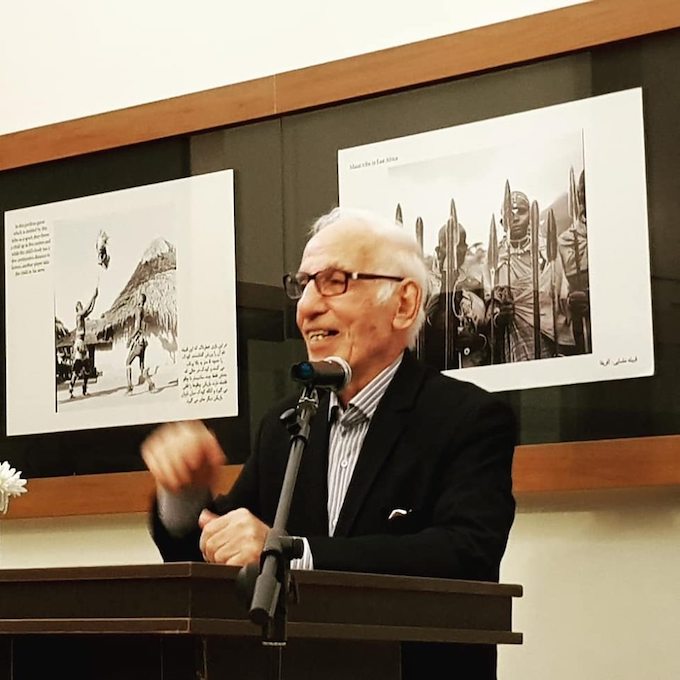

I encountered younger brother Issa Omidvar, now 88, at an amusing public talk he gave at the museum last month, and I took the opportunity to interview him. His elder brother, Abdullah, 90, lives with his wife in Chile where they started a business.

Their adventures and survival were of special interest to me, as in 1972-74 I had spent a year travelling across Africa in two stages from Cape Town to Algiers, driving across the Sahara Desert in the process – chicken feed compared with the brother’s two global odysseys totalling a decade, 1954-1964.

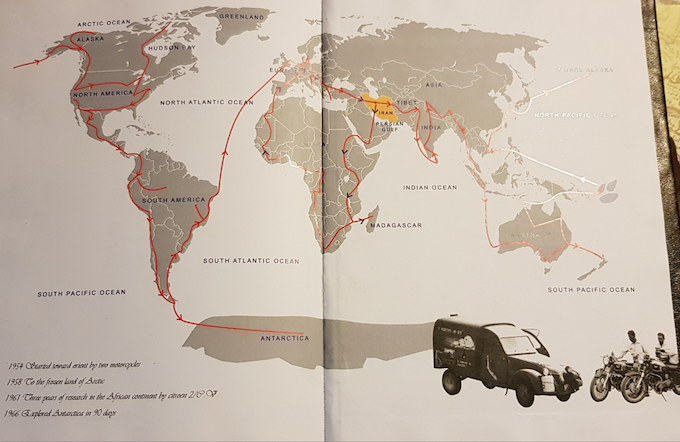

Travelling east from Tehran via the country’s second city of Mashhad, the brothers first passed through Afghanistan, then Pakistan, India, south-east Asia and Australia, where they lived with Aboriginals. Eventually they crossed the Pacific to Rapanui and headed north through Alaska and Canada into the Arctic.

After a huge sweep through North and South America, they rounded off their first seven-year journey in Antarctica.

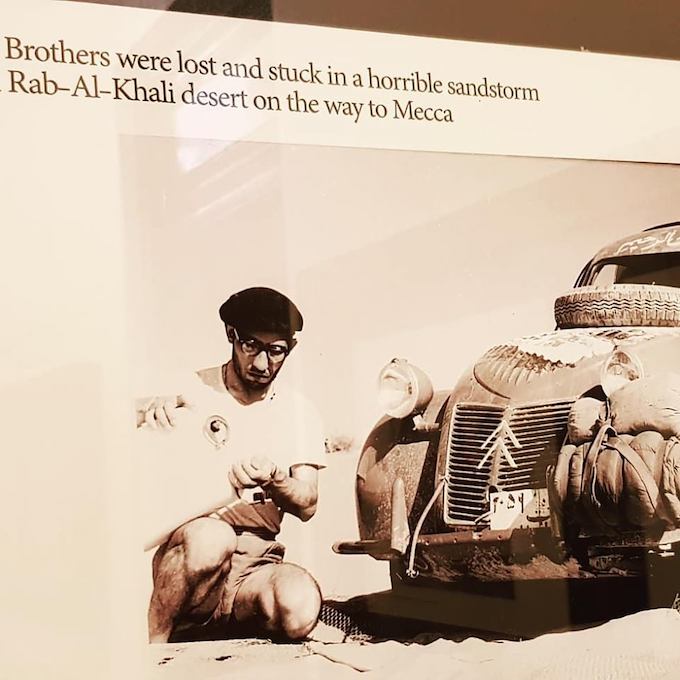

Following a short break back home in Iran, the brothers set off again on a second exploration trip in a Citroën 2CV across Africa, including the Congo and the pygmy country of the Ituri jungle. They filmed their exploits along the way.

As Guardian travel writer Kevin Rushby wrote in 2013, “they created a visual record that is now a milestone in film history, a documentary record of a vanished world: peoples, cultures and even entire countries that no longer exist.”

According to Issa at his public Tehran talk, “We had the opportunity of visiting, and holding talks with most presidents, prime ministers, kings and cultural personalities of the world.”

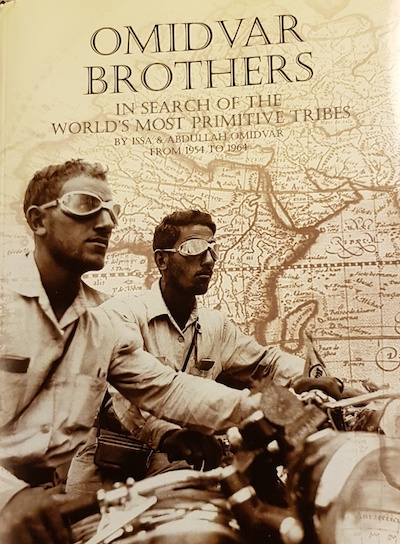

However, many of the communities that they described in their remarkable book, Omidvar Brothers: In Search of the World’s Most Primitive Tribes, and showed in their various documentaries, no longer live as they once did, untouched in remote locations.

The Omidvar mission – they started off on their motor bikes in 1954 with the equivalent of merely $90 each in their pockets – was about scientific research and documentary making.

In the book preface Nikfarjam, then international affairs director of Aryan International Tourism Magazine, wrote that the Omidvar brothers were “the greatest explorers, adventurers and seekers of knowledge in 10 years of scientific expedition … searching [for] the most primitive tribal people in unknown lands of our planet earth who had never had contact with the outsider before …

“The live stories … will take the reader … to the most severe climatic and various geographical conditions living with unknown savage tribes.

“In fact, [this] scientific research has been so adventurous and exciting that hardly anyone can believe all are true and serious.”

But true they are.

The Iranian Organisation of Cultural Patrimony added in their foreword: “The fruits of their exploration are … great photographic and documentary films, hunting equipment and household utensils from diverse primitive tribes.

“With such a treasure, unique of its kind, the Omidvar Brothers Museum illustrates the wealth, complexity and diversity of human culture … and of human organisation that succumbed, victims of the world’s explosive development.”

Browsing through the illustrated book in Farsi (an English-language edition also exists), I came across these sample passages:

Kabul

“The first capital we visited was Kabul, a city with few main streets. There were few vehicles, which was a blessing, but there were lots of bicycles on the streets. Even prominent and well-known people used bicycles … One day we were surprised to see the chancellor of Kabul University riding an old bicycle.”

Jalalabad

“We passed through Jalalabad towards the border of Pakistan. To our delight we discovered a wedding party with riflemen and prepared to photograph … Unknown to us … was that this tribe didn’t like to have photos taken, especially of their ceremonies. When they saw us their cheerful shouts immediately changed to a cry of death and they began hurling hundreds of rocks at us.”

Sri Lanka (then Ceylon)

“It is said that Adam and Eve were expelled from Heaven and began their earthly life in Ceylon. We boarded the ship called Safinet al Arab … She was 43 years old and in considerable disrepair with a capacity of 1100 people, mostly pilgrims for Mecca … on the third day one of the Muslim passengers died, creating chaos. The authorities had no choice but to bury the body at sea. From that moment we feared that a similar fate might befall us.”

Hyderabad

“The Kite War is as significant for the people of Hyderabad in India as horse racing is for the British, bullfighting for the Spanish and football for the Brazilians … Common people and nobles alike participate in the kite competitions, betting enormous amounts of money.”

Lucknow

“When we arrived it was a national holiday – the Colour Festival … We were settled at the university dormitory and sleeping when at dawn we awoke with a loud noise. The students pounded on the door and looked as if they had escaped from Hell. Each with a bucketful of water colours and after rubbing some colour on our forehead, they threw each other in a colourful pond.”

Himalayas

“In order the climb the Himalayas, we had to pass through dangerous, swampy forests to reach the slopes pf the mountains. We had not seen such a dreadful forest … Such a threat becomes a hundredfold at night. The roars of wild animals, especially tigers, made us shake with fear … We touched our legs and found a small creature, a leech. We turned on our flashlight and saw a great number of leeches sucking our blood.”

Amazon

“We were nearing the horrifying tribe of Jivaro [in the headwaters of the Marañon River]. We reached a settlement of huts made of wild sugarcane leaves and bamboo around a clearing. All the men and women with painted bodies were standing by their huts waiting for us. Although they had seen other white people, it was interesting for them to see us – maybe at that moment they were measuring our heads to be shrunken!”

In my interview with Issa Omidvar, he stressed the critical importance of the value of international travel as a contribution to “global understanding and peace”.

Dr David Robie travelled independently and with no political “minders”.

David Robie talks to Issa Omidvar about the brothers’ research travel philosophy. Video: Del Abcede/Café Pacific

- Part 1: Iran a hugely ‘friendly’ country behind the sabre-rattling

- Part 2: 10 reasons why tourists must visit Iran

- Part 3: Iran’s great global adventurers

- The Omidvar Brothers Museum