On September 18, 2013, two Greenpeace International activists were arrested during a peaceful protest at a Gazprom oil platform in the Russian Arctic. A week later, the entire 30-member crew of their ship was in a Russian jail awaiting trial on charges of “hooliganism” and “piracy”. The story of the Arctic 30, as they came to be known, was one heard around the world, and one that Peter Willcox — also skipper of the original Rainbow Warrior which was bombed by French secret agents in Auckland Harbour in 1985 — writes about in his new book Greenpeace Captain. Read this exclusive excerpt.

On September 18, 2013, two Greenpeace International activists were arrested during a peaceful protest at a Gazprom oil platform in the Russian Arctic. A week later, the entire 30-member crew of their ship was in a Russian jail awaiting trial on charges of “hooliganism” and “piracy”. The story of the Arctic 30, as they came to be known, was one heard around the world, and one that Peter Willcox — also skipper of the original Rainbow Warrior which was bombed by French secret agents in Auckland Harbour in 1985 — writes about in his new book Greenpeace Captain. Read this exclusive excerpt.

Maggy had been watching a live Greenpeace feed in our home in Maine, anxiously awaiting the moment when my head would pop out from behind the huge prison door. Just before I walked out, the video feed was lost and she missed the big moment. She didn’t know I was out until I called her from the car to tell her I was drinking Alexander’s brandy.

While I was relieved to be out of jail, during the car ride from Kresty Prison to the hotel my joy was tempered by worrying about the reception I would receive there from the Arctic 30 who had been released before me. Would they blame me for their incarceration?

I had certainly made decisions that contributed to our arrest and the arrest of the ship, but then again, not one of us had anticipated the muscular response from the Russians. As I exited the car and walked into the lobby of the hotel, my concern grew. Would they vent their anger at me, or would I just get the cold shoulder?

The first people I saw were my shipmates Sini, Camila Speziale, and Alexandra “Alex” Harris. They saw me in the same instant and immediately moved toward me with their arms raised. I realized the three were all opening their arms to me. Seconds later we were in a group hug. Their shoulders were anything but cold. It was the best I had felt in a very long time.

The hotel had been selected by the police so they could keep an eye on us while we were out on bail. We assumed the hotel was bugged, and there was an undercover cop in a van parked across the street from the hotel.

While we wanted to give him the finger, we would flash him the peace sign instead. That probably pissed him off even more. Having him there was their way of keeping us under pressure. The peace sign was our way of saying, “We don’t give a shit.”

Like being in purgatory

Although we were out on bail, we were still under indictment and not allowed to leave the city. It was kind of like being in purgatory, but after being in prison it was still a major improvement in living arrangements. I was able to see my wife, my daughters, Skype with friends, and — of course — be interviewed by newspapers, websites, and TV and radio broadcasters all over the world.

At this same time, Putin was preparing a mass amnesty bill. Officially, the amnesty bill was to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Russian constitution. The reality was the bill was an attempt to polish up Russia’s record on human rights just weeks before the start of their Winter Olympics. Our lawyers were hoping that the Arctic 30 would be included in the bill, but no one knew for sure who was included or not. The more publicity we got, the better the chance we’d make it into the bill, so we focused on that.

In prison we had been cut off from the outside world. We were pretty much in the dark (literally, in some cases) and just trying to keep our spirits up.

There were a few TVs in prison, but since the government controls the media we didn’t see any news covering the efforts to put pressure on Putin to release us. We got some reports via our lawyers, Greenpeace, letters and, eventually, phone calls with loved ones, but that was just the tip of the iceberg.

Every written word we received in the prison was read by the Russians and translated into Russian before we got them. Everything we received had typed notes with Russian translations that were taped or stapled to the originals, including the ‘Free the Arctic 30’ greeting cards made by eight-year-old children in Africa. I still have a stack of them with all of the Russian translations.

Peter Willcox, writing with Ronald Weiss in the forthcoming book “Greenpeace Captain”

Now that we were on the outside, it was just becoming apparent to me (and to the rest of the Arctic 30) just how much publicity we were getting. It’s an amazing feeling to realize that hundreds of “Free the Arctic 30” protests demanding your release have taken place in dozens of countries around the world. Words can’t describe it, so I won’t try. The bottom line is that the international reaction makes me believe that what Greenpeace is doing is deeply appreciated and important.

Impressive supporters list

Thousands of people had protested in front of numerous Russian embassies. Letters from statesmen, world leaders, religious leaders, celebrities, actors, and media figures from every corner of the globe joined in the effort to release us. It’s an impressive list, and it’s not just the length of the list that’s amazing, it’s the breadth of it: twelve Nobel Prize winners. Paul McCartney. The Pope. Madonna. (It’s not too often that the Pope and Madonna are in agreement on anything!) Angela Merkel, François Hollande, and David Cameron. Desmond Tutu. Even the VP of Iran, Dr Masonmeh Ehtekar (she’s also the head of Iran’s EPA) supported us. The list goes on and on.

One protest letter that was especially important to me was written to Putin by Pete Seeger, the family friend, folksinger, and my boss on the Clearwater so many years before. It was Pete who put me on the path I was still following years later. Pete passed away at age 94 just a few weeks after I got back to Maine, so I never saw him again.

When you’re in prison you have a lot of free time on your hands. Often you find yourself thinking about happier times and places and people that you miss. A lot of those times were with Pete, singing and sailing and saving the river.

It was hard on Maggy to have me imprisoned in a hostile country, particularly since it happened such a short time after we were married. And a good chunk of that time I had been at sea on other actions. For her part, she always put up a brave front, and never stopped fighting for our release.

She helped organise rallies from Maine to Connecticut, wrote letters and editorials, and urged governors and senators to write Putin. Maggy was a real emotional anchor for me during this stormy period of false dawns and dark threats. She’s an amazing woman and I’m lucky to have finally landed her.

Holding our breath

All of us in St Petersburg (the Arctic 30, family, friends, lawyers, diplomats, and supporters) were holding our breath until the amnesty bill was passed. When it passed, it released close to 25,000 prisoners — some petty criminals, some political prisoners, all kinds of people — but not us. The bill did not include “hooligans” — our “category of criminal.” It was, yet again, another shock and disappointment.

Still, there was some hope. A few days later, the Duma (the Russian legislature) passed an amendment to the bill that included those charged with hooliganism — that meant us, and Pussy Riot, among others. We were greatly relieved, of course.

We were close to home free. (“Home” and “free,” two words that will always mean a little more to me now.) Still, we had to wait for the inevitable paperwork to get processed, getting our passports back etc.

Who knew how long that was going to take? It looked like “I’ll be Home for Christmas” wasn’t on the cards, but we were hoping to be back in time for New Year’s Eve.

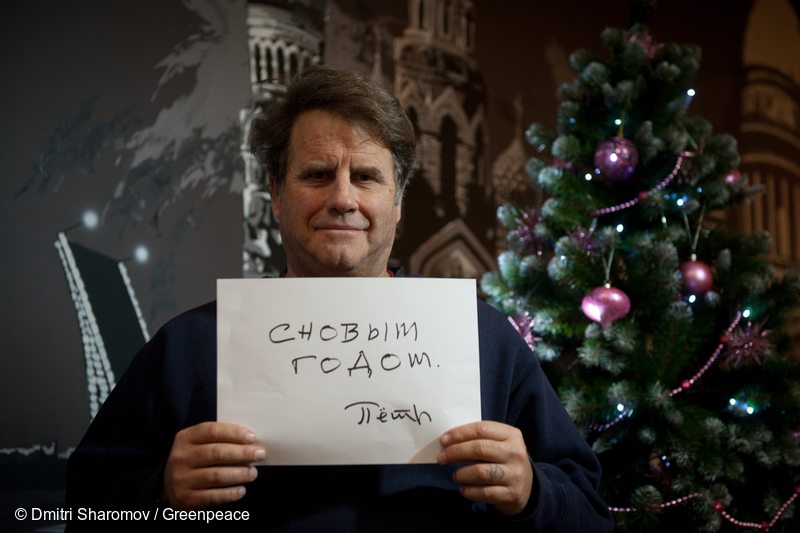

There is a video called “Thank You” that Greenpeace put together after we were released. It shows highlights of the protests all around the world, and then we — the Arctic 30 — thank all of the people who took action to secure our release. (You can watch it yourself.)

I think I speak for all of us when I say that if it were not for all of their support, we might still be languishing in a Russian prison somewhere.

Thank you. Thank you. Spasibo. Spasibo.

This excerpt was with permission from the author from chapter 19 of Greenpeace Captain: My Adventures in Protecting the Future of Our Planet, by Peter Willcox with Ronald Weiss. Available from Thomas Dunne Books. Copyright © 2016. Learn more about the forthcoming book Greenpeace Captain, available April 19, 2016. In Australia, New Zealand and Oceania, Greenpeace Captain will be available through Penguin Random House.