ANALYSIS: By Ali Mirin

Papua New Guinea and Indonesia have formally ratified a defence agreement a decade after its initial signing.

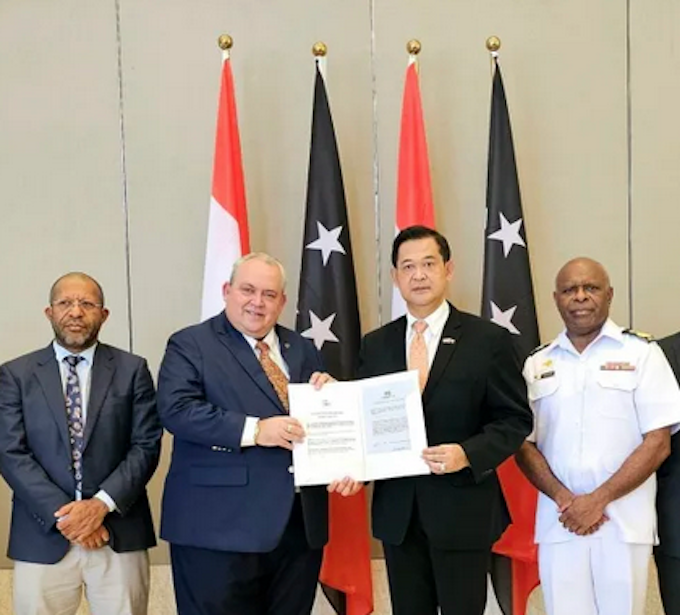

PNG’s Foreign Minister Justin Tkatchenko and the Indonesian ambassador to the Pacific nation, Andriana Supandy, convened a press briefing in Port Moresby on February 29 to declare the ratification.

The agreement enables an enhancement of military operations between the two countries, with a specific focus on strengthening patrols along the border between Papua New Guinea and Indonesia.

According to Tkatchenko as reported by RNZ Pacific citing Benar News, “The Joint border patrols and different types of defence cooperation between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea of course will be part of the ever-growing security mechanism.”

“It would be wonderful to witness the collaboration between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, both now and in the future, as they work together side by side. Indonesia is a rising Southeast Asian power that reaches into the South Pacific region and dwarfs Papua New Guinea in population, economic size and military might,” added the minister.

In recent years, Indonesia has been asserting its own regional hegemony in the Pacific amid the rivalries of two superpowers — the United States and China.

Indonesia’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Retno Marsudi reiterated Indonesia’s commitment to bolster collaboration with Pacific nations amid heightened geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific region during the recent 2024 annual press statement held by the minister for foreign affairs at the Asian-African Conference in Bandung.

Diverse Indigenous states

The Pacific Islands are home to diverse sovereign Indigenous states and islands, and also home to two influential regional powers, Australia and New Zealand. This vast diverse region is increasingly becoming a pivotal strategic and political battleground for foreign powers — aiming to win the hearts and minds of the populations and governments in the region.

Numerous visible and hidden agreements, treaties, talks, and partnerships are being established among local, regional, and global stakeholders in the affairs of this vast region.

The Pacific region carries great importance for powerful military and economic entities such as China, the United States and its coalition, and Indonesia. For them, it serves as a crucial area for strategic bases, resource acquisition, food, and commercial routes.

For Indigenous islanders, states, and tribal communities, the primary concern is around the loss of their territories, islands, and other vital cultural aspects, such as languages and traditional wisdom.

The crumbling of Oceania, reminiscent of its past colonisation by various European powers, is now occurring. However, this time it is being orchestrated by foreign entities appointing their own influential local pawns.

With these local pawns in place, foreign monarchs, nobility, warlords, and miscreants are advancing to reshape the region’s fate.

The rejection by the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) to acknowledge the representation of West Papua by the United Liberation for West Papua (ULMWP) as a full member of the regional body in August 2023 highlights the diminishing influence of MSG leaders in decision-making processes concerning issues that are deemed crucial by the Papuan community as part of the “Melanesian family affairs”.

Suspicion over ‘external forces’

This raises suspicion of external forces at play within the Melanesian nations, manipulating their destinies. The question arises, who is orchestrating the fate of the Melanesian nations?

Is it Jakarta, Beijing, Washington, or Canberra?

In a world characterised by instability, safety and security emerges as a crucial prerequisite for fostering a peaceful coexistence, nurturing friendships, and enabling development.

The critical question at hand pertains to the nature of the threats that warrant such protective measures, the identities of both the endangered and the aggressors, and the underlying rationale and mechanisms involved. Whose safety hangs in the balance in this discourse?

And between whom does the spectre of threat loom?

If you are a realist in a world of policymaking, it is perhaps wise not to antagonise the big guy with the big weapon in the room. The Minister of Papua New Guinea may be attempting to underscore the importance of Indonesia in the Pacific region, as indicated by his statements.

If you are West Papuan, it makes little difference whether one leans towards realism or idealism. What truly matters is the survival of West Papuans, in the midst of the significant settler colonial presence of Asian Indonesians in their ancestral homeland.

West Papuan refugee camp

Two years ago, PNG’s minister stated the profound existential sentiments experienced by the West Papuans in 2022 while visiting a West Papuan refugee community in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea.

During the visit, the minister addressed the West Papuan refugees with the following words:

“The line on the map in middle of the island (New Guinea) is the product of colonial impact. These West Papuans are part of our family, part of our members and part of Papua New Guinea. They are not strangers.

“We are separated only by imaginary lines, which is why I am here. I did not come here to fight, to yell, to scream, to dictate, but to reach a common understanding — to respect the law of Papua New Guinea and the sovereignty of Indonesia.”

These types of ambiguous and opaque messages and rhetoric not only instil fake hope among the West Papuans, but also produce despair among displaced Papuans on their own soil.

The seemingly paradoxical language coupled with the significant recent security agreement with the entity — Indonesia — that has been oppressing the West Papuans under the pretext of sovereignty, signifies one ominous prospect:

Is PNG endorsing a “death decree” for the Indonesian security apparatus to hunt Papuans along the border and mountainous region of West Papua and Papua New Guinea?

Security for West Papua

Currently, the situation in West Papua is deteriorating steadily. Thousands of Indonesian military personnel have been deployed to various regions in West Papua, especially in the areas afflicted by conflict, such as Nduga, Yahukimo, Maybrat, Intan Jaya, Puncak, Puncak Jaya, Star Mountain, and along the border separating Papua New Guinea from West Papua.

On the 27 February 2024, Indonesian military personnel captured two teenage students and fatally shot a Papuan civilian in the Yahukimo district. They alleged that the deceased individual was affiliated with the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNB), although this assertion has yet to be verified by the TPNPB.

Such incidents are tragically a common occurrence throughout West Papua, as the Indonesian military continue to target and wrongfully accuse innocent West Papuans in conflict-ridden regions of being associated with the TPNPB.

These deplorable acts transpired just prior to the ratification of a border operation agreement between the governments of the Papua New Guinea and Indonesia.

As the security agreement was being finalised, the Indonesian government announced a new military campaign in the highlands of West Papua. This operation, is named as “Habema” — meaning “must succeed to the maximum” — and was initiated in Jakarta on the 29 February 2024.

Agus Subiyanto, the Indonesian military command and police command stated during the announcement:

“My approach for Papua involves smart power, a blend of soft power, hard power, and military diplomacy. Establishing the Habema operational command is a key step in ensuring maximum success.”

The looming military operation in West Papua and its border regions, employing advanced smart weapon technology poised a profound danger for Papuans.

A looming humanitarian crisis in West Papua, PNG, broader Melanesia and the Pacific region is inevitable, as unmanned aerial drones discern targets indiscriminately, wreak havoc in homes, and villages of the Papuan communities.

The Indonesian security forces have increasingly employed such sophisticated technology in conflict zones since 2019, including regions like Intan Jaya, Yahukimo, Maybrat, Pegunungan Bintang, and other volatile regions in West Papua.

Consequently, villages have been razed to the ground, compelling inhabitants to flee to the jungle in search of sanctuary — an exodus that continues unabated as they remain displaced from their homes indefinitely.

On 5 April 2018, the Indonesian government announced a military operation known as Damai Cartenz, which remains active in conflict-ridden regions, such as Yahukimo, Pegunungan Bintang, Nduga, and Intan Jaya.

The Habema security initiative will further threaten Papuans residing in the conflict zones, particularly in the vicinity of the border shared by Papua New Guinea and West Papua.

There are already hundreds of people from the Star Mountains who have fled across to Tumolbil, in the Yapsie sub-district of the PNG province of West Sepik, situated on the border. They fled to PNG because of Indonesia’s military operation (RNZ 2021).

According to RNZ News, individuals fleeing military actions conducted by the Indonesian government, including helicopter raids that caused significant harm to approximately 14 villages, have left behind foot tracks.

The speaker explained that Papua New Guineans occasionally cross over to the Indonesian side, typically seeking improved access to basic services.

The PNG government has been placing refugees from West Papua in border camps, the biggest one being at East Awin in the Western Province for many decades, with assistance from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

How should PNG, UN respond?

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007, article 36, states that “Indigenous peoples, in particular those divided by international borders, have the right to maintain and develop contacts, relations and cooperation with their own members as well as other peoples across borders”.

Over the past six years, regional and international organisations, such as the Melanesian Spearheads groups (MSG), Pacific islands Forum (PIF), Africa, Caribbean and Pacific states (ACP), the UN’s human rights commissioner as well as dozens of countries and individual parliaments, lawyers, academics, and politicians have been asking the Indonesian government to allow the UN’s human rights commissioner to visit West Papua.

However, to date, no response has been received from the Indonesian government.

What does this security deal mean for West Papuans?

This is not just a simple security arrangement between Jakarta and Port Moresby to address border conflicts, but rather an issue of utmost importance for the people of Papua.

It concerns the sovereignty of a nation — West Papua — that has been unjustly seized by Indonesia, while the international community watched in silence, witnessing the unfurling and unparalleled destruction of human lives and the ecological system.

There is one noble thing the foreign minister of PNG and his government can do: ask why Jakarta is not responding to the request for a UN visit made by the international community, rather than endorsing an ‘illegal security pact’ with the illegal Indonesia colonial occupier over his supposed “family members separated only by imaginary lines”.

Ali Mirin is a West Papuan from the Kimyal tribe of the highlands that share a border with the Star Mountain region of Papua New Guinea. He graduated last year with a Master of Arts in International Relations from Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia.