REVIEW: By Heather Devere

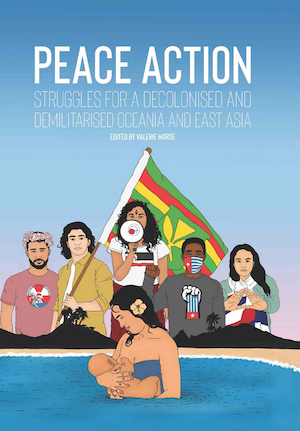

The aims of Peace Action: Struggles for a Decolonised and Demilitarised Oceania and East Asia as stated by the editor, Valerie Morse, are “to make visible interconnections between social struggles separated by the vast expanse of Te Moana Nui-A-Kiwi [the Pacific Ocean] … to inspire, to enrage and to educate, but most of all, to motivate people to action” (p. 11).

It is an opportunity to learn from the activists involved in these struggles. Published by the Left of the Equator Press, there are plenty of clues to the radical ideas presented. The frontispiece points out that the publisher is anti-copyright, and the book is “not able to be reproduced for the purpose of profit”, is printed on 100 percent “post consumer recycled paper”, and “bound with a hatred for the State and Capital infused in every page”.

By their nature, activists take action and do things rather than just speak or write about things, as is the academic tradition, so this is an important, unique, and rare opportunity to learn from their insights, knowledge, and experience.

Twenty-three contributors representing some of the diverse Peoples of Aotearoa, Australia, China, Hawaii, Japan, New Caledonia, Samoa, Tahiti, Tokelau, Tonga, and West Papua offer 13 written chapters, plus poetry, artworks, and a photo essay. The range of topics is extensive too, including the history of the Crusades and the doctrine of discovery, anti-militarist and anti-imperialist movements, land reclamation movements, nuclear resistance and anti-racist movements, solidarity and allyship.

Both passion and ethics are evident in the stories about involvement in decolonised movements that are “situated in their relevant Indigenous practice” and anti-militarist movements that “actively practice peace making” (p. 11).

While their activism is unquestioned, the contributors come with other impressive credentials. Not only do they actively put into practice their strong values, but many are also researchers and scholars. Dr Pounamu Jade Aikman (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Apakura, Ngāti Wairere, Tainui, Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Te Rangi, Te Arawa and Ngāti Tarāwhai) holds a Fulbright Scholarship from Harvard University. Mengzhu Fu (a 1.5 generation Tauiwi Chinese member of Asians Supporting Tino Rangatiratanga) is doing their PhD research on Indigenous struggles in Aotearoa and Canada-occupied Turtle Islands. Kyle Kajihiro lectures at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa and is a board member of Hawai’i Peace and Justice. Yamin Kogoya is a West Papuan academic from the Yikwa-Kogoya clan of the Lani tribe in the Papuan Highlands. Ena Manuireva is an academic and writer who represents the Mā’ohi Nui people of Tahiti. Dr Jae-Eun Noh and Dr Joon-Shik Shin are Korean researchers in Australian universities. Dr Rebekah Jaung, a health researcher, is involved in Korean New Zealanders for a Better Future.

Several of the authors are working as investigators on the prestigious Marsden project entitled “Matiki Mai Te Hiaroa: #ProtectIhumātao”, a recent successful campaign to reclaim Māori land. These include Professor Jenny Bol Jun Lee-Morgan (Waikato, Ngāti Mahuta and Te Ahiwaru), Frances Hancock (Irish Pākehā), Carwyn Jones (Ngāti Kahungunu), Qiane Matata-Sipu (Te Waiohua ki te Ahiwaru me te Ākitai, Waikato Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Pikiao), and Pania Newton (Ngāpuhi, Waikato, Ngāti Mahuta and Ngāti Maniapoto) who is co-founder and spokesperson for the SOUL/#ProtectIhumātao campaign.

Others work for climate justice, peace, Indigenous, social justice organisations, and community groups. Jungmin Choi coordinates nonviolence training at World Without War, a South Korean antimilitarist organisation based in Seoul. Mizuki Nakamura, a member of One Love Takae coordinates alternative peace tours in Japan. Tuhi-Ao Bailey (Ngāti Mutunga, Te Ātiawa and Taranaki) is chair of the Parihaka Papakāinga Trust and co-founder of Climate Justice Taranaki.

Zelda Grimshaw, an artist and activist, helped coordinate the Disrupt Land Forces campaign at a major arts fair in Brisbane. Arama Rata (Ngāruhine, Taranaki and Ngāti Maniapoto) is a researcher for WERO (Working to End Racial Oppression) and Te Kaunoti Hikahika.

Some are independent writers and artists. Emalani Case is a writer, teacher and aloha ‘āina from Waimea Hawai’i. Tony Fala (who has Tokelauan, Palagi, Samoan, and Tongan ancestry) engages with urban Pacific communities in Tāmaki Makaurau. Marylou Mahe is a decolonial feminist artist from Haouaïlou in the Kanak country of Ajë-Arhö. Tina Ngata (Ngäti Porou) is a researcher, author and an advocate for environmental Indigenous and human rights.

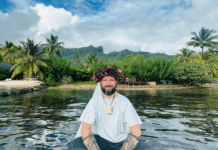

Jos Wheeler is a director of photography for film and television in Aotearoa.

Background analysis for this focus on Te Moana Nui A Kiwi, provides information about the concepts of imperial masculinity, infection, ideas from European maritime law Mare Liberum, that saw the sea as belonging to everyone. These ideas steered colonisation and placed shackles, both figuratively and physically, on Indigenous Peoples around the world.

In the 17th century, Japan occupied the country of Okinawa, now also used as a training base by the US military. European “explorers” had been given “missions” in the 18th century that included converting the people to Christianity and locating useful and profitable resources in far-flung countries such as Aotearoa, Australia, New Caledonia and Tahiti.

In the 19th century, Hawai’i was subject to US imperialism and militarisation.

In the 20th century, Western countries were “liberating other nations” and dividing them up between them, such as the US “liberation” of South Korea from Japanese colonial rule. The Dutch prepared West Papua for independence 1960s after colonisation, but a subsequent Indonesian military invasion left the country in a worse predicament.

However, the resistance from the Indigenous Peoples has been evident from the beginnings of imperialist invasions and militarisation of the Pacific, despite the arbitrary violence that accompanied these. Resistance continues, as the contributors to Peace Action demonstrate, and the contributions reveal the very many faces and facets of non-violent resistance that works towards an eventual peace with justice.

Resistance has included education, support to help self-sufficiency, medical and legal support, conscientious objection, human rights advocacy, occupation of land, coordinating media coverage, visiting sites of significance, being the voice of the movement, petitions, research, writing, organising and joining peaceful marches, coordinating solidarity groups, making submissions, producing newsletter and community newspapers, relating stories, art exhibitions and installations, visiting churches, schools, universities, conferences, engaging with politicians, exploiting and creating digital platforms, fundraising, putting out calls for donations and hospitality, selling T-shirts and tote bags, awareness-raising events, hosting visitors, making and serving food, bearing witness, musical performances, photographic exhibitions, film screenings, songs on CDs.

In order to mobilise people, activists have been involved in political engagement, public education, multimedia engagement, legal action, protests, rallies, marches, land and military site occupations, disruption of events, producing food from the land, negotiating treaties and settlements, cultural revitalisation, community networking and voluntary work, local and international solidarity, talanoa, open discussions, radical history teaching, printmaking workshops, vigils, dance parties, mobile kitchens, parades, first aid, building governance capacity, sharing histories, increasing medical knowledge.

Activist have been prompted to act because of anger, disgust, and fear. The oppressors are likened to big waves, to large octopuses (interestingly also used in racist cartoons to depict Chinese immigrants to Aotearoa), to giants, to a virus, slavers, polluters, destroyers, exploiters, thieves, rapists, mass murderers, war criminals, war profiteers, white supremacists, racists, brutal genocide, ruthless killers, subjugators, fearmongers, demonisers, narcissistic sociopaths, and torturers.

The resisters often try to “find beauty in the struggle” (Case, p. 70), using imagery of flowers and trees, love, dancing, song, braiding fibers or leis, dolphins, shark deities, flourishing food baskets, fertile gardens, pristine forests, sacred valleys, mother earth, seashells, candlelight, rainbows, rays of the rising sun, friendship, alliance, partners, majestic lowland forests, ploughs, watering seeds, and harvesting crops.

Collaboration in resistance requires dignity, respect, integrity, providing safe spaces, honesty, openness, hard work without complaint, learning, cultural and spiritual awareness. The importance of coordination, cooperation and commitment are emphasised.

And readers are made aware of the sustained energy that is needed to follow through on actions.

The aim of Peace Action is to inspire, enrage, educate and motivate. These chapters will appeal mostly to those already convinced, and this is deliberately so.

In these narratives, images we have guidance as to what is needed to be an activist. We admire the courage and bravery, we are educated into the multitude of activities that can be undertaken, and the immense amount of work in planning and sustaining action.

This can serve as a handbook, providing plans of action to follow. Richness and creativity are provided in the fascinating and informative narratives, storytelling, and illustrations.

I find it difficult to criticise because its goal is clear, there is no pretence that it is something else, and it achieves what it sets out to do. It remains to be seen whether peace action will follow. But that will be up to the readers.

- Peace Action: Struggles for a Decolonised and Demilitarised Oceania and East Asia, edited by Valerie Morse. Te Whanganui-A-Tara (Wellington): Left of the Equator Press, 2022, 178 pages. NZ$25.99. ISBN 9780473634452.

Dr Heather Devere is former director of practice, National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Otago, and chair of the Asia Pacific Media Network (APMN). This review is published in collaboration with Pacific Journalism Review.