OBITUARY: By Tony Fala

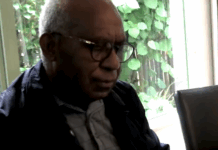

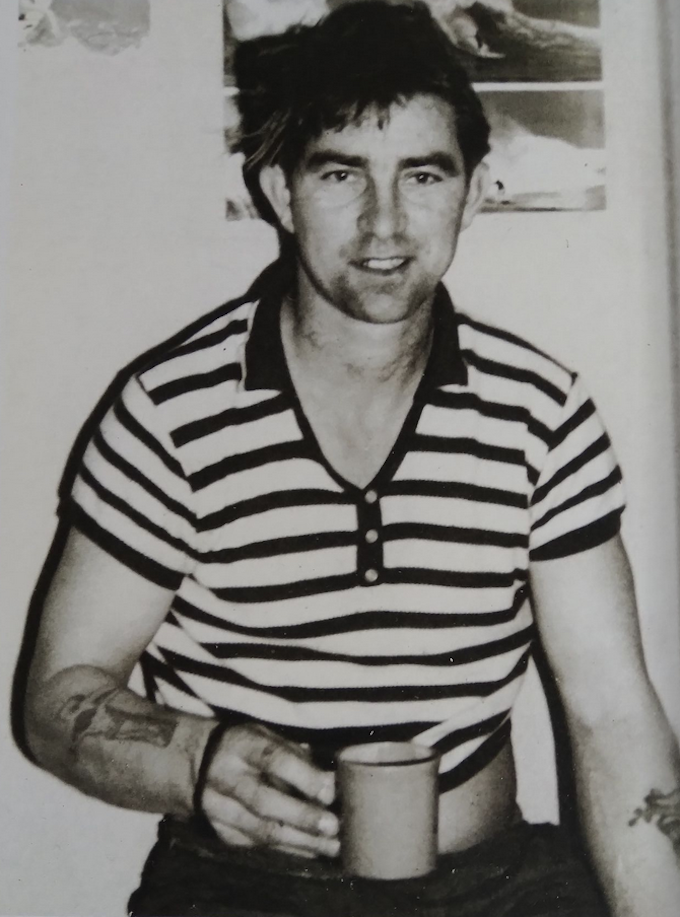

James “Jimmy” O’Dea (18 October 1935-27 November 2021) was a mighty activist, community organiser, family man, and working-class defender. He died in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland after a long, brave battle against prostate cancer. He was 86.

Friends, neighbours, and activists representing many historical struggles joined the O’Dea whanau at All Saints Chapel in Purewa Cemetery on December 4 for a celebration of Jimmy’s life.

Chapel orators narrated O’Dea’s life as a much-loved husband, father, grandfather, and uncle. Moreover, speakers gave rich, oral historical accounts of his service in the whakapapa of many struggles in Aotearoa and the world.

The speakers:

Kereama Pene:

Minister Kereama Pene of Ngati Whatua opened the service with a poignant reflection on O’Dea’s 62 years of service for Māori communities in Aotearoa. Pene spoke of Jimmy O’Dea’s close friendships with Whina Cooper and a generation of kuia and kaumatua who have all passed over. He said O’Dea attended many marae throughout the country over his long life.

Pat O’Dea:

His eldest son, Pat O’Dea, expanded upon Kereama Pene’s fine introductory comments. He spoke about his father arriving in Aotearoa in 1957. Patrick wove oral histories of his father’s long commitment to many struggles in Aotearoa.

Pat elaborated upon Jimmy O’Dea’s many years of work for Māori communities.

Pat O’Dea explained that his father first got involved in anti-racist activism for Māori in 1959 when Jimmy supported Dr Henry Bennett. This eminent doctor was refused a drink at the Papakura Hotel in South Auckland because he was Māori.

Pat O’Dea told stories concerning Jimmy O’Dea’s involvement in the Māori Land March of 1975.

The audience was told that Jimmy O’Dea drove the bus for the land march in 1975 — a bus Jimmy received from Ponsonby People’s Union leader Roger Fowler.

Pat O’Dea wove wonderful narratives concerning Jimmy’s role in the 1977 struggle at Takaparawhau (Bastion Point). He articulated rich oral histories regarding Jimmy’s close friendship with Takaparawhau leader Joe Hawke. Pat also spoke of the genesis of that struggle in his oration.

Pat O’Dea also spoke of his father’s long commitment to Moana (Pasifika) communities in Aotearoa. He told a wonderful story of how Jimmy O’Dea, and his Māori friend, Ann McDonald, both helped prevent a group of Tongan “overstayers” from being deported by NZ Police by boat during the Dawn Raids in the mid-1970s in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Narrating stories of his father’s long commitment to the CPNZ, the trade union movement, and the working class in Aotearoa, Pat O’Dea spoke of how Jimmy was hated by employers and union leaders alike because he always told the working-class people the truth!

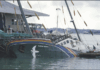

Pat O’Dea narrated stories concerning Jimmy’s involvement in the anti-nuclear struggle in Aotearoa from 1962. Pat recounted the story of his father voyaging out into the ocean on a tin dinghy with outboard motor — protesting against the arrival of a US submarine making its way up Waitemata Harbour in 1979.

Pat also briefly addressed Jimmy’s long years of work with the Aotearoa front of the international struggle against Apartheid in South Africa.

Pat also highlighted Jimmy’s anti-racist labours as one landmark in his many contributions to activism.

Kevin O’Dea:

Jimmy’s son Kevin O’Dea joined the celebration by video link from Australia. He introduced the audience to his father as a wonderful family man who loved music and poetry. Kevin elaborated upon the aroha that conjoined Jimmy’s large, extended family. He read a poem for his father about the place of music in times of grief and healing.

Nanda Kumar:

Nanda Kumar spoke on behalf of Jimmy’s Indo-Fijian wife Sonya and the extended family. A niece of Sonya, Nanda talked of her Uncle Jimmy’s rich contributions to family life at Kupe Street in Takaparawhau.

Jimmy’s grandsons:

One of Pat O’Dea’s sons gave a profound mihi in te reo for his grandfather. He also read an Irish poem to honour Jimmy. This grandson said that the greatest lesson he learnt from his grandfather was that one should always defend those who cannot defend themselves.

Another of Jimmy’s grandsons gave a strong mihi. He told the story of travelling with his grandfather and learning how much Jimmy cared for people. This grandson performed a musical tribute for his grandfather on the flute.

Taiaha Hawke:

Taiaha Hawke of Ngati Whatua gave a noble oration concerning Takaparawhau. He informed guests of the close working relationship between his father Joe Hawke and Jimmy O’Dea as all three men fought for Takaparawhau in the middle 1970s. Taiaha told rich stories of the spirituality that underpinned that struggle — in words too precious to be recorded here. He affirmed his whanau’s commitment to working together with the O’Dea family on a project to honour Jimmy.

Alastair Crombie:

Alastair Crombie was Jimmy’s neighbour on Kupe Street, Takaparawhau, for 20 years. He told the audience of how he exchanged plates of food with the O’Dea’s — and how his empty plates were always returned heaped with wonderful Indian cooking from Sonya’s kitchen! Alistair shared stories of how his friendship with Jimmy transcended political differences.

Andy Gilhooly:

Jimmy’s friend Andy Gilhooly introduced the audience to James O’Dea’s early life in Ireland. He told the story of Jimmy’s early life of poverty as an orphan boy. Andy spoke of Jimmy’s natural brilliance in the Gaelic language at school: But Jimmy was unable to complete his schooling because of poverty. He talked of Jimmy’s love of the sea — and how O’Dea joined the Merchant Marine and sailed from Ireland to Australia and Aotearoa. Finally, Andy located Jimmy’s love for the oppressed in O’Dea’s Irish Catholic upbringing.

Stories about Jimmy after the funeral:

After the funeral, Roger Fowler told me that Jimmy was heavily involved in anti-Vietnam War activism in the 1960s and 1970s. He talked of Jimmy’s long years of work in the anti-apartheid struggle to free South Africa. Moreover, Roger spoke of Jimmy’s long commitment to the Palestinian cause. He also elaborated upon Jimmy’s dedication to his Irish homeland through work in support of the James Connolly Society.

Jimmy’s place in the whakapapa of struggles in Aotearoa:

I only knew Jimmy O’Dea as a friend and fellow activist (in SWO and beyond) for 26 years. The experts on Jimmy’s place in the wider whakapapa of struggles in Aotearoa between 1959-2021 are those who fought alongside him on many campaigns.

Representatives of the Te Tino Rangatiratanga and anti-apartheid struggles in Aotearoa have already paid tribute to Jimmy after he died. John Minto’s obituary for Jimmy is superlative.

The stories of Jimmy O’Dea in struggle in Aotearoa are borne living in the oral histories held by many good people — including Kevin O’Dea; Patrick O’Dea; the wider O’Dea whanau; Grant Brookes; Joe Carolan; Lynn Doherty & Roger Fowler; Roger Gummer; Hone Harawira; Joe Hawke; Taiaha Hawke; Bernie Hornfeck; Will ‘IIolahia; Barry & Anna Lee; John Minto; Tigilau Ness; Pania Newton; Len Parker; Kereama Pene; Delwyn Roberts; Oliver Sutherland; Annette Sykes; Alec Toleafoa; Joe Trinder, and many others.

Memories of Jimmy O’Dea are held in the hearts of many other ordinary folk — who, like Jimmy, and people mentioned above, helped build collective struggles and collective narratives of emancipation in Aotearoa and abroad.

Jimmy and Te Tiriti:

In conclusion, I feel Jimmy embodied the culture, history, language, and values of his Irish people. His life also pays testimony to the hope that Māori and Pakeha can come together as peoples under Te Tiriti.

Distinguished Ngati Kahu, Te Rarawa, and Ngati Whatua leader Margaret Mutu provides an insightful introduction to Māori understandings of Te Tiriti in her 2019 article, “‘To honour the treaty, we must first settle colonisation’ (Moana Jackson): the long road from colonial devastation to balance, peace and harmony”

I believe Jimmy upheld a vision of partnership outlined by Professor Mutu in the above article. As a Pakeha, Jimmy honoured his Māori Te Tiriti partner throughout his life in Aotearoa.

James “Jimmy” O’Dea upheld Māori Te Tino Rangatiratanga under Te Tiriti in his actions and words.

Perhaps Pakeha can find a model for partnership under Te Tiriti in Jimmy’s rich life — a model of partnership characterised by genuine power-sharing, mutual respect, and a commitment to working through legitimate differences with aroha and patience. When this occurs, there will be a place for Kiwis of all cultures in Aotearoa.

For me, Jimmy O’Dea’s lifelong contributions to a genuine, full partnership between Pakeha and Tangata Whenua under Te Tiriti constitute one of his greatest legacies for all living in Aotearoa.

The author, Tony Fala, thanks the O’Dea whanau for the warm invitation to attend Jimmy’s funeral. The author thanks Roger Fowler for his generous korero regarding Jimmy’s activism. This article only tells a small part of Jimmy’s story. Finally, Fala wishes to acknowledge the life and work of two of Jimmy O’Dea’s mighty comrades and contemporaries — Pakeha activists Len Parker and Bernie Hornfeck. Len served working-class, Māori, and Pacific communities for more than 60 years in Tamaki Makaurau. Bernie Hornfeck spent more than 60 years working as an activist, community organiser, and forestry worker.