ANALYSIS: By Clare Corbould, Deakin University

Since the September 11 terror attacks, there has been no hiding from the increased militarisation of the United States. Everyday life is suffused with policing and surveillance.

This ranges from the inconvenient, such as removing shoes at the airport, to the dystopian, such as local police departments equipped with decommissioned tanks too big to use on regular roads.

This process of militarisation did not begin with 9/11. The American state has always relied on force combined with the de-personalisation of its victims.

- READ MORE: Why is it so difficult to fight domestic terrorism? 6 experts share their thoughts

- Calculating the costs of the Afghanistan War in lives, dollars and years

- Police with lots of military gear kill civilians more often than less-militarised officers

The army, after all, dispossessed First Nations peoples of their land as settlers pushed westward. Expanding the American empire to places such as Cuba, the Philippines, and Haiti also relied on force, based on racist justifications.

The military also ensured American supremacy in the wake of the Second World War. As historian Nikhil Pal Singh writes, about 8 million people were killed in US-led or sponsored wars from 1945–2019 — and this is a conservative estimate.

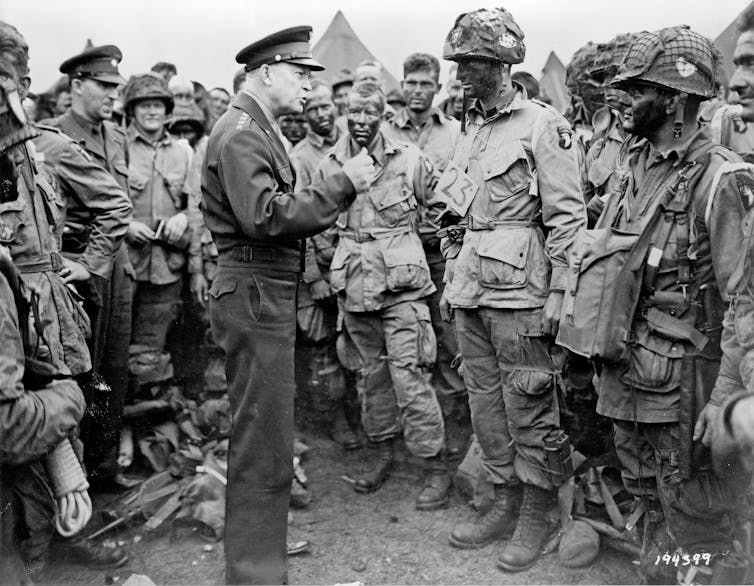

When Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican and former military general, left the presidency in 1961, he famously warned against the growing “military-industrial complex” in the US. His warning went unheeded and the protracted conflict in Vietnam was the result.

The 9/11 attacks then intensified US militarisation, both at home and abroad. George W. Bush was elected in late 2000 after campaigning to reduce US foreign interventions.

The new president discovered, however, that by adopting the persona of a tough, pro-military leader, he could sweep away lingering doubts about the legitimacy of his election.

Waging war on Afghanistan within a month of the Twin Towers falling, Bush’s popularity soared to 90 percent. War in Iraq, based on the dubious assertion of Saddam Hussein’s “weapons of mass destruction”, soon followed.

The military industrial juggernaut

Investment in the military state is immense. 9/11 ushered in the federal, cabinet-level Department of Homeland Security, with an initial budget in 2001-02 of US$16 billion. Annual budgets for the agency peaked at US$74 billion in 2009-10 and is now around US$50 billion.

This super-department vacuumed up bureaucracies previously managed by a range of other agencies, including justice, transportation, energy, agriculture, and health and human services.

Centralising services under the banner of security has enabled gross miscarriages of justice. These include the separation of tens of thousands of children from parents at the nation’s southern border, done in the guise of protecting the country from so-called illegal immigrants.

More than 300 of the some 1000 children taken from parents during the Trump administration have still not been reunited with family.

The post-9/11 Patriot Act also gave spying agencies paramilitary powers. The act reduced barriers between the CIA, FBI, and the National Security Agency (NSA) to permit the acquiring and sharing of Americans’ private communications.

These ranged from telephone records to web searches. All of this was justified in an atmosphere of near-hysterical and enduring anti-Muslim fervour.

Only in 2013 did most Americans realise the extent of this surveillance network. Edward Snowden, a contractor working at the NSA, leaked documents that revealed a secret US$52 billion budget for 16 spying agencies and over 100,000 employees.

Normalisation of the security state

Despite the long objections of civil liberties groups and disquiet among many private citizens, especially after Snowden’s leaks, it has proven difficult to wind back the industrialised security state.

This is for two reasons: the extent of the investment, and because its targets, both domestically and internationally, are usually not white and not powerful.

Domestically, the 2015 Freedom Act renewed almost all of the Patriot Act’s provisions. Legislation in 2020 that might have stemmed some of these powers stalled in Congress.

And recent reports suggest President Joe Biden’s election has done little to alter the detention of children at the border.

Militarisation is now so commonplace that local police departments and sheriff’s offices have received some US$7 billion worth of military gear (including grenade launchers and armoured vehicles) since 1997, underwritten by federal government programmes.

Militarised police kill civilians at a high rate — and the targets for all aspects of policing and incarceration are disproportionately people of colour. And yet, while the sight of excessively armed police forces during last year’s Black Lives Matter protests shocked many Americans, it will take a phenomenal effort to reverse this trend.

The heavy cost of the war on terror

The juggernaut of the militarised state keeps the United States at war abroad, no matter if Republicans or Democrats are in power.

Since 9/11, the US “war on terror” has cost more than US$8 trillion and led to the loss of up to 929,000 lives.

The effects on countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Syria, and Pakistan have been devastating, and with the US involvement in Somalia, Libya, the Philippines, Mali, and Kenya included, these conflicts have resulted in the displacement of some 38 million people.

These wars have become self-perpetuating, spawning new terror threats such as the Islamic State and now perhaps ISIS-K.

Those who serve in the US forces have suffered greatly. Roughly 2.9 million living veterans served in post-9/11 conflicts abroad. Of the some 2 million deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, perhaps 36 percent are experiencing PTSD.

Training can be utterly brutal. The military may still offer opportunities, but the lives of those who serve remain expendable.

Life must be precious

Towards the end of his life, Robert McNamara, the hard-nosed Ford Motor Company president and architect of the United States’ disastrous military efforts in Vietnam, came to regret deeply his part in the military-industrial juggernaut.

In his 1995 memoir, he judged his own conduct to be morally repugnant. He wrote,

We of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations who participated in the decisions on Vietnam acted according to what we thought were the principles and traditions of this nation. We made our decisions in light of those values. Yet we were wrong, terribly wrong.

In interviews with the filmmaker Errol Morris, McNamara admitted, obliquely, to losing sight of the simple fact the victims of the militarised American state were, in fact, human beings.

As McNamara realised far too late, the solution to reversing American militarisation is straightforward. We must recognise, in the words of activist and scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore, that “life is precious”. That simple philosophy also underlies the call to acknowledge Black Lives Matter.

The best chance to reverse the militarisation of the US state is policy guided by the radical proposal that life — regardless of race, gender, status, sexuality, nationality, location or age — is indeed precious.

As we reflect on how the United States has changed since 9/11, it is clear the country has moved further away from this basic premise, not closer to it.![]()

Dr Clare Corbould, Associate Professor, Contemporary Histories Research Group, Deakin University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.