By Jasmine Chia in Bangkok

It is an unlikely combination: the white stars of the West Papuan and Myanmar flags, side by side.

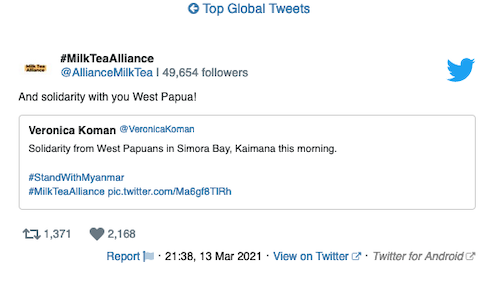

“West Papua Stands with Myanmar,” the sign said, posted by Indonesian human rights lawyer Veronica Koman. In another poignant picture, a small group of West Papuans stand at Simora Bay at the port town of Kaimana holding a sign that reads: “We Stand With Myanmar.”

Popular activist Twitter account @AllianceMilkTea responds: “And solidarity with you West Papua!”

The latest member of the Milk Tea Alliance is a little-known region in ASEAN, south of the Pacific Ocean and bordered by the Halmahera, Ceram and Banda seas.

West Papua is better known for its Raja Ampat or “Four Kings” Islands, the majestic archipelago which contains the richest marine biodiversity on earth. But, like other members of the Milk Tea Alliance, it is a region scarred by subjugation and tyranny.

While the brutality of Min Aung Hlaing’s army is horrifyingly public, West Papuans protest killings and an independence movement that has largely been erased from history.

In December 2020, Benny Wenda, a political exile in Britain, declared himself head of West Papua’s first government-in-exile under the Papua Merdeka “Free West Papua” movement. That same month, the United Nations Human Rights Office called on all sides – West Papuan separatists and the Indonesian security forces – to de-escalate violence in the territory that has seen the deaths of activists, church workers and Indonesian officials.

As the Papua Merdeka campaign picks back up, this article surveys the history and recent state violence in the region. Flickers of a “Papuan Spring” seem faint in a March that has emboldened Southeast Asian dictators. But that the voices of a region long suppressed are being heard is an achievement in and of itself.

fascinating (and inspiring) article on the Milk Tree Alliance https://t.co/tLSVWCYz9m

— Peter Beinart (@PeterBeinart) October 15, 2020

History of West Papuan independence claims

History is always a fraught tool in the battle between states and their challengers. Indonesian claims to control over West Papua date back to the “restoration” of the region to the Republic of Indonesia in a pivotal 1969 referendum, the ironically named “Act of Free Choice” (AFC).

Central to the AFC’s controversy was the musyawarah (consultation) system, agreed upon by the Foreign Ministers of Indonesia and Netherlands, which decreed that the vote for West Papuan “restoration” would be conducted by a select group of representatives rather than the entire West Papuan population.

The AFC was overseen by representatives from the UN Secretary-General’s team, giving the Indonesian government its desired stamp of international legitimacy.

Yet, as studies produced by the University of Sydney show, since 1963 President Suharto’s military government worked to deliberately quash expressions of a unique Papuan identity. Shows of Papuan culture were declared “subversion”, West Papuan nationalists were placed under detention, and representatives were carefully selected for what the musyawarah.

The script is familiar to any observer of Thailand’s equally controversial 2016 “constitutional referendum”. As an AFP correspondent noted in 1969, “Indonesian troops and officials are waging a widespread campaign of intimidation to force the Act of Free Choice in favor of the Republic.”

President Suharto declared that voting against the AFC was an act of treason. Eventually, 1026 voters were chosen of a population of 815,906, all of whom voted unanimously for integration.

In the aftermath of the AFC vote, West Papua was immediately declared a Military Operation Zone. West Papuan historians like John Rumbiak highlighted the military and police repression that soon followed, especially against activists protesting the appropriation of traditional land and forests by mining firms and timber estates.

Thousands of troops were deployed in response to growing protest movements in the 1990s, with planned “black operations” against independence leaders.

Ever since, West Papua has been caught in a cycle of violence. Indonesian armed forces accuse guerillas of inciting separatist violence, justifying their crackdowns on various villages.

Under Indonesian law, raising the West Papuan flag carries a sentence of up to 15 years in prison. Separatists like the armed West Papua National Liberation Army continue to wage a low-key insurgency in their quest for self-rule.

According to rights group Human Rights and Peace in Papua, 60,000 West Papuans have been displaced in the conflict.

“Our independent nation was stolen in 1963 by the Indonesian government,” Wenda said in an interview with the New York Times, “We are taking another step toward reclaiming our legal and moral rights.”

Wenda, like the authors of the University of Sydney study, argues that there is a “silent genocide” taking place in West Papua, as thousands of Indonesians are killed by Indonesian state actors in their battle against West Papuan separatists.

A 2004 Yale Law School report similarly concluded that “the Indonesian government has committed proscribed acts with the intent to destroy the West Papuans,” including subjecting Papuan men and women to “acts of torture, disappearance, rape, and sexual violence.”

This is compounded systematic resource exploitation, compulsory (and often unpaid) labor, as well as the rapid spread of HIV/AIDS and malnutrition.

West Papuan claims to independence date back to 1961, according to then Papua People’s Congress leader Theys Hiyo Eluay.

Eluay, later murdered by Indonesian Kopassus soldiers, insisted that Papua had never been culturally and politically integrated with Indonesia – a claim seemingly reinforced by the ethnic difference of the majority Papua population that inhabit the region.

In the narrative both Eluay and Wenda have shared, West Papua declared sovereignty on 1 December 1961 as the Dutch gave up claims to Indonesia.

“This same vision of West Papua’s history and sovereignty can be found among ordinary Papuan people,” writes academic Nino Viartasiwi.

Papuan Spring? The 2019 Uprising

West Papuans’ newfound alliance with the Milk Tea Alliance is part of its renewed attempt to bring international attention to the violence they have faced at the hands of Indonesian security forces for half a century.

Last year, a #PapuanLives Matter campaign spotlighted the death of a 19-year old student at the hand of security forces as part of the global focus on police brutality. Activists highlighted the racialized elements of the West Papuan struggle.

In the words of UK-born Indonesian actor and activist Hannah Al Rashid, quoted in The Guardian: “I stand in solidarity with Papuan Lives Matter, because…I have observed the way in which people of darker skin [in Indonesia] have been treated unfairly.”

These 2020-2021 movements are smaller resurrections of the larger 2019 West Papua Uprising, or simply, ‘The Uprising.’ From August to September 2019, protests swept 22 towns in West Papua and 3 cities in Indonesia in response to an incident in which Indonesian soldiers shouted ‘monkey’ repeatedly at West Papuan students in Malang.

In response, over 6000 members of the Indonesian security forces were deployed to quell the Uprising. 61 civilians – including 35 indigenous West Papuans – died in the crackdown.

According to TAPOL, a campaigning platform for human rights, peace and democracy in Indonesia, 22,800 civilians were displaced during the Uprising.

The cycle of resistance and crackdown is not new to Southeast Asia. West Papuans face the additional struggle of opposing a security force that they do not claim as their own, but it is an experience the Karen, Kachin, Chin or Wa peoples in Myanmar currently share.

Their solidarity with the Milk Tea Alliance is fitting, drawing on a movement that has built regional solidarity and momentum for other struggles against authoritarianism.

With any luck, the unlikely solidarity across the two starred flags may bring the West Papuan struggle back into the international spotlight. If not, the conflict will continue in the shadows, as it has done since the dawn of the 21st century.

Jasmine Chia is a writer and contributor to the Thai Enquirer.