COMMENTARY: By Murray Horton in Christchurch

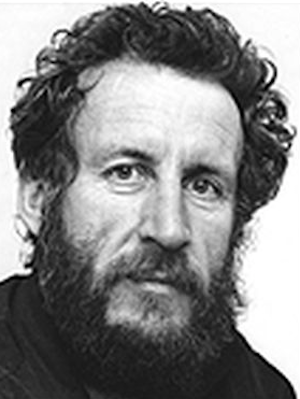

Owen Wilkes, an internationally renowned peace researcher and Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA) founder, died in 2005, aged 65 (see my obituary in Watchdog 109, August 2005). And yet, 16 years later, I’m still learning more about him and gaining insights into his life and character.

In late 2020 I was contacted, out of the blue, by an octogenarian Kiwi expat in Oslo, who had been a good friend of Owen’s in Scandinavia in the 1970s and 1980s and then for most of the rest of Owen’s life.

In 1978, I and my then partner (Christine Bird, a fellow CAFCINZ founder and first chairperson of CAFCA) accompanied Owen on a “spy trip” through Norway’s northernmost province, the one bordering the former Soviet Union, which gave me my first glimpse of the sort of domes with which I’ve become so familiar at the Waihopai spy base during the last 30 plus years.

- READ MORE: ‘Better to go now’: Owen Wilkes, 1940-2005

- Owen Wilkes, an up-front activist, a great organiser and always in the front lines

We met this expat Kiwi while in Oslo. Although we were strangers, he immediately recognised us as New Zealanders the second we stepped off the train at his station.

Why? Because of the distinctive shabbiness of our dress. I hadn’t heard from him in decades. In 2020, he went to the trouble of contacting an NZ national news website to get my email address.

He told me that he had a small collection of Owen’s letters and other material about him, and as he was decluttering and couldn’t think of any Scandinavian home for them, would I like them?

I was happy to do so. Reading them brought back vivid memories from more than 40 years ago, none more so than in connection with that “spy trip”.

Thrived in Scandinavia

Owen thrived in Scandinavia, and particularly loved his 18 months in Norway, paying Norwegians the highest accolade of being “good jokers”. All up, he lived six years in Scandinavia, most of it in Sweden, where he worked for the world-famous Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

He applied his unique talents to researching in both countries e.g., he identified the entire security police staff by the simple expedient of ringing every block of particular extension numbers.

In 1978, Christine Bird and I did our Big OE, part of which included crossing the former Soviet Union on the Trans-Siberian Express from the Pacific coast and staying with Owen in his Stockholm apartment.

In this most sophisticated of northern European cities, he still dressed and acted like The Wild Man of Borneo (when I inquired about toilet paper, he told me that he used the phonebook). It was quite a sight to visit the SIPRI office full of oh, so proper Swedes and there was Owen working away at his desk, naked except for shorts.

We met up with him for a reason, which was to accompany him on a “spy” trip through Norway’s northernmost Finnmark province, which was chokka with North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) military bases and lots of Waihopai-like spy bases, the first time I ever saw those distinctive domes.

Norway was then one of only two NATO members with a land border with the Soviet Union (the other being Turkey).

Mad Norwegian adventure

Off we went, the three of us, on this mad adventure, travelling by boat, train, bus and hitchhiking. We slept in a tent wherever we could pitch it.

Bird and I went by bus right up to the Soviet border; Owen got the deeply suspicious driver to drop off him beforehand so that he could walk up and check out a spy base in the border zone (photography was strictly forbidden near any of these bases, even at Oslo Airport, because it was also an Air Force base). From memory, he told the bus driver that he was a bird watcher (he had his ever-present binoculars to prove it).

He told us that if he hadn’t rejoined us within a couple of days, it would mean that he had been arrested and to ring the office in Oslo to let them know. Right on time he turned up.

We duly delivered the rolls of film back to the International Peace Research Institute in Oslo (PRIO) and they were used in a book co-authored by Owen and Nils Petter Gleditsch, the PRIO Director. The book, Uncle Sam’s Rabbits (a pun on the rabbit ear aerials used at some of the listening post spy bases) caused such a sensation in Norway that both authors were charged, tried, convicted and fined for offences under the Official Secrets Act.

Much more excitement was to come, not long after, in Sweden. Security agents swooped on Owen as he was returning from a bike trip around islands between Sweden and Finland, he was held incommunicado for several days amid sensational headlines about a Soviet spy being arrested (this was the sort of stuff that gave his poor old Mum palpitations back in Christchurch).

He was eventually released and charged with offences under Sweden’s Official Secrets Act (after his death, NZ media coverage mistakenly said that he was convicted of espionage offences. That means spying for a foreign country. He wasn’t charged with any such offence, let alone convicted).

Forded Arctic river in shorts to covertly enter Soviet Union

This was at the height of the Cold War, when neutral Sweden was being particularly paranoid about Soviet spies (not helped when a Soviet Whiskey class submarine got embarrassingly stuck in Stockholm Harbour, the famous “Whiskey On The Rocks” episode).

Owen’s trial was very high profile, attracting international media attention. At first, he was convicted and sentenced to six months’ prison. He never served a day of that, because he appealed, and the sentence was suspended but he was fined heavily and ordered expelled from Sweden for 10 years (he used to joke that he should have appealed for it to be increased to 20 years).

The 2020 package of material from Oslo added one vital detail I didn’t know about that “spy trip” we did with him. The Kiwi expat wrote to a work mate of Owen’s, after his death: “He once even crossed the Norwegian-Soviet border in the high north, wading across an icy river in his shorts and was there several hours – only a few people know about this.

It doesn’t bear thinking about what could have happened to him, or so-called international relations, if he’d been jumped on by the vodka-sodden Soviet frontier guards. As unshaven as Owen. He would have managed though …

No wonder that bus driver was so suspicious of him. There is great irony in the fact that both the Norwegian and Swedish security agencies suspected Owen of being some sort of a Soviet spy and both prosecuted him; yet if he’d been caught on his covert visit to the Soviet Union, he would have doubtless been presented to the world as a Western spy.

A 1981 letter that Owen wrote to his Oslo mate shed some light on his arrest and detention for several days by the Swedish Security Service (SAPO).

“Overall, it wasn’t such bad fun. I had a clear conscience all along and I wasn’t scared that SAPO would try and plant evidence or anything like that… So, I slept well at night, found the interrogations intellectually stimulating, read several novels. Getting out was fun too…”

I can personally testify as to how much Owen enjoyed being locked up. We were among a group of people arrested inside the US military transport base at Christchurch Airport during a 1988 protest (the base is still there). This is from my 2005 Watchdog obituary of Owen, cited above:

“It was a weekend, so we were bailed after a few hours to appear later in the week”.

“But that didn’t suit Owen, he had things to do and didn’t want to be mucking around with inconvenient court appearances. So, he refused bail and opted to stay locked up for 24 hours so that the cops had to produce him at the next day’s court hearing (which was more convenient for him), where he duly got bail.

“He told me that he’d found some old Reader’s Digests in the cells and had had a wonderful uninterrupted time reading their Rightwing conspiracy theories about how the KGB was behind the 1981 assassination attempt on Pope John Paul 11. In the meantime, I was left to deal with his then partner, who was frantic about how come he’d ended up in custody, as that hadn’t been part of their South Island holiday plans. In the end, we fought the good fight in court, were convicted and got a small fine each”.

Getting to read his Swedish security file

A letter to his Oslo mate at the turn of the century says that he learned that Swedish police files on him would be among those now available to the people who were the subjects of them. He wrote, from New Zealand, asking for access to their files on him from 1978-81.

He got a reply saying he could have access to 1025 pages and that he had two months to do so. Owen had been planning a Scandinavian trip with his partner, May Bass, and this was the icing on the cake for him (“she is going to find something else to do while I am poring through the archives in Stockholm”).

When I last saw Owen, in 2002, he told that me that the file showed that the Swedish authorities were absolutely convinced that he was a Soviet spy and there was circumstantial evidence of which he had been unaware – for instance, he had been monitoring a whole lot of radio frequencies broadcasting from the Soviet Union, and in the case of one, he had apparently stumbled onto the means of communication between the KGB (former Soviet spy agency) and their agent in Sweden.

He had no idea but this reinforced the Swedish spooks’ idea that he was a Soviet spy, rather than an insatiably curious peace researcher.

By contrast, to this day, the NZ Security Intelligence Service has refused to release anything but a fraction of its file on him (see my “Owen Wilkes’ SIS File. A bit more feleased, a decade after first smidgen”, in Watchdog 150, April 2019).

The SIS says it holds six volumes on Owen. It still deems the great majority of that too sensitive to be released, even to his one remaining blood relative – his younger brother.

In 1982, after six years of high drama in Scandinavia, he returned home in a blaze of publicity and CAFCINZ (as CAFCA was then) sent him around the country on an extremely successful speaking tour.

Christchurch academic, Professor Bill Willmott, nominated him for the 1982 Nobel Peace Prize (funnily enough, he didn’t win it. It was never likely that the Scandinavians would ever award their homegrown prize to a peace activist who had been convicted for “spying” on them).

A copy of Willmott’s nomination letter is among the material I was sent. After his involuntary return, Owen never lived overseas again, but he continued to be of ongoing interest to Scandinavian media.

A 1983 Norwegian article reported on Owen from where he was living in the Karamea district. It was titled: “’Spy’ yesterday, farmer today”.

Extreme adventurer, renouncing Peace Movement

Owen wasn’t a big fan of Sweden but he absolutely loved Norway. It gave him full scope for the extreme adventures that he loved, whether on foot, in the water, on skis or on a bike.

His letters describing some of his adventures are wonderful examples of travel writing, although not for the fainthearted reader. This is his description of what happened when he boarded a coastal ferry after one such jaunt through days of unrelenting rain:

“.. I noticed the people were looking rather strangely at me, which I assumed was just because of the way I went squilch-squelch when I walked, and the way a little rivulet would wend its way out from under my chair when I sat down. Then I chanced to look in a mirror, and discovered that my skin had gone all soft and wrinkly and puffy, so that I looked like a cadaver that had been simmered in caustic soda solution”.

He would have fitted right in to any movie about the zombie apocalypse.

His letters shed light on various fascinating aspects of his life and personality. In the 1990s he basically and publicly renounced the Peace Movement (I refer you to my 2005 Watchdog obituary, cited above. See the subheadings “Leaving the Peace Movement” and “Writer of crank letters”). A 1993 letter to his Oslo mate gives a small taste of this.

It lists his disagreements with “Greenpeas [not a typo. MH] …on quite a few issues. Some of their campaigns are just great, but some of them are pretty bloody stupid, I reckon. And it is only recently that they’ve started going screwy” (he then details six areas of disagreement).

“Grumble, grumble, it’s no wonder I am getting offside with the peace movement around these parts, is it… Anyway, I am sort of getting out of the peace movement”.

Another 1993 letter to Oslo (the only handwritten one) is a fascinating, hilarious and white-knuckle account of how – after the unexpected death of his father in Christchurch – he and his brother tried to get their bedridden mother moved by small plane from Christchurch to the brother’s district of Karamea.

A classic Canterbury norwester put paid to that and they had to land at a rural airstrip (after the sheep had been chased off it). The journey had to be finished by ambulance and took 26 hours. Owen’s parents died within a few months of each other, in 1993. I knew both of them and Becky and I attended both funerals.

Owen was a depressive, which played a role in his 2005 suicide. That same 1993 handwritten letter concluded with this: “There’s an election coming up in 3 weeks, but I feel quite detached. Basically, I think we’re all totally doomed + the civilisation is into its final orgy of environmental destruction before the end. Rather than trying to improve the future by changing the present, I plan on documenting the past, just in case civilisation is re-established in some distant future + its people are in a mood to learn from our past. Hence my archaeology. It’s a choice between archaeology or alcoholism, I reckon”.

Pleasure and sadness

Owen Wilkes was a fascinating and simultaneously infuriating man. He has been dead for 16 years and this quite unexpected package of material goes back more than 40 years. But that passage only reinforces for me what a loss he is, both to the progressive movement nationally and globally, but also as a person, an indomitable adventurer, and as a friend and colleague.

It was with both pleasure and sadness that I read through this material. It brought back so many memories.

As for the Oslo expat, he and I went on to have an extensive correspondence in late 2020 and on into 2021. And not just about Owen but about many other people and topics. He has permanently lived outside NZ since the 1960s but we still have people in common.

For example, in 1960s Christchurch he was involved with the Monthly Review and knew Wolfgang Rosenberg. I sent him my Watchdog obituary of Wolf (114, May 2007). The upshot of all this was that he insisted on sending CAFCA a donation.

Thank you, Owen, you’re the gift that keeps on giving.

Murray Horton is a political activist, advocate and researcher. He is organiser of the Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA) and has been an advocate of a range of progressive causes for the past five decades.