ANALYSIS: By Professor Derrick Armstrong

A traditional view of the tension between research and policy suggests that researchers are poor at communicating their research findings to policy-makers in clear and unambiguous ways.

I am arguing that this is an outdated view of the relationship between research and policy. Science, including social science, and policy come together in many interesting and creative ways.

This does not mean that tensions between the two are dissolved but the conversation between research and policy centre as much on ideological and pragmatic issues as it does upon the strength of the scientific evidence itself.

READ MORE: The DevNet 2018 conference

Researchers are increasingly “smart” in the ways that they seek to influence public debate while policy-makers genuinely value the insights that research can provide in supporting political and policy agendas that goes beyond simply legitimating pre-existing policy choices.

For example, in climate change debates science cannot be seen simply as an arbiter of “truth” that informs policy and political decision-making. Science also plays an advocacy role in alliance with some social interests against others.

Likewise, policy can draw on science but it can also reject the evidence of science where scientific evidence is weighed against the interests of other powerful voices in the policy-process.

Oceans research and policy provides a good example of this more sophisticated relationship between science and policy and suggests some of the significant disconnects and tensions that challenge the relationship as well as how creative tensions between the two operate in practice. Three areas of disconnect can be identified.

Practical disconnection

The first of these is practical disconnection of regulation with regard to the Oceans. An integrated legal framework for the ocean might be considered critical for progress towards meeting the objectives of SDG 14 (Life under the Sea) but complexity and fragmentation present many challenges which are both sectorial and geographical.

National laws lack coordination across different ocean-related productive sectors, conservation, and areas of human wellbeing. In addition, these laws are disconnected from the regulation of land-based activities that negatively impact upon the ocean – agriculture, industrial production and waste management (including ocean plastic).

These disconnections are compounded by limited understanding of the role of international human rights and economic law, as well as the norms of indigenous peoples, development partners and private companies.

Disconnected science is itself a problem in this area. Ocean science is still weak in most countries due to limited holistic approaches for understanding cumulative impacts of various threats to ocean health such as climate change, pollution, coastal erosion and overfishing.

Equally, scientific understanding of the effectiveness of conservation and management responses is poor, so that the productivity limits and recovery time of ecosystems cannot be easily predicted.

Even when science is making progress, effective science-policy interfaces are often poorly articulated at all levels. As a result, there are significant barriers to effectively measuring progress in reaching SDG14.

Oceans research policies rare

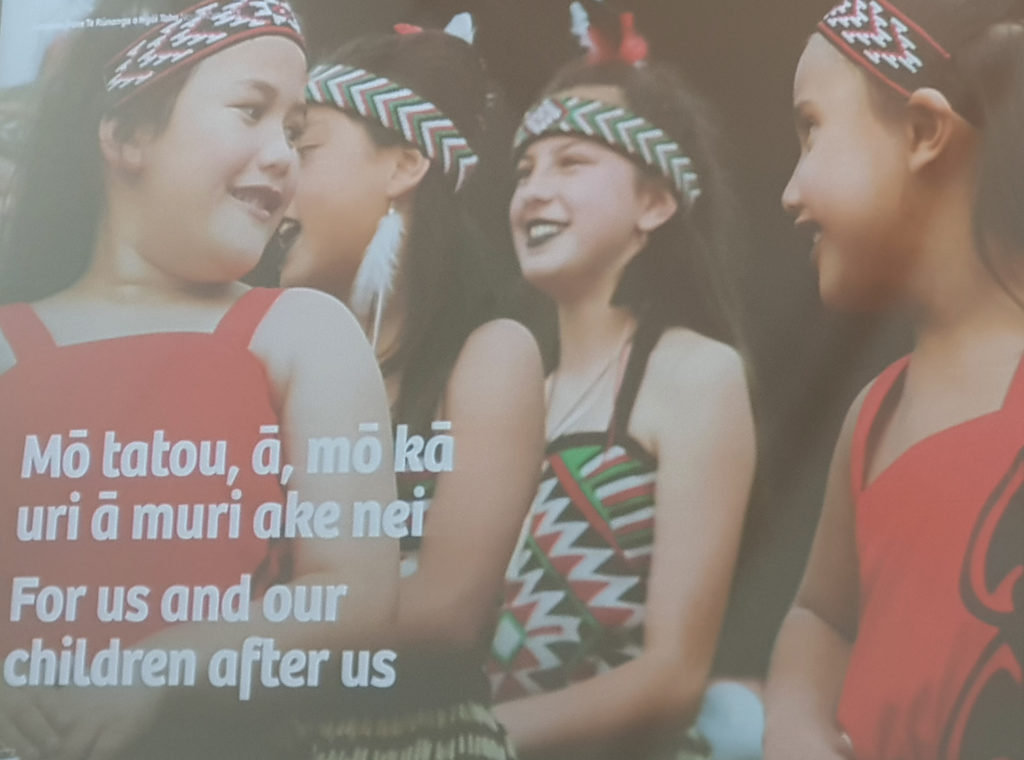

National oceans research policies to support sustainable development are rare. This is compounded by limited understanding of the role of different knowledge systems, notably the traditional knowledge of indigenous people.

Third, there is a disconnected dialogue. Key stakeholders, most notably the communities most dependent on ocean health, are not sufficiently involved in developing and implementing ocean management; yet, they are most disproportionately affected by their negative consequences.

More positively, there are some good examples of effective science-policy diplomacy collaborations and networks. For example, in the Pacific my own university (University of the South Pacific) has worked very effectively to support Pacific island countries, especially Fiji, Marshall Islands, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, to successfully lead arguments at the International Maritime Organisation for international commitments to reduced carbon emission targets for shipping.

Technical, scientific support has been critical to support the advocacy of Pacific leaders and their ability to mobilise wider political support.

Building the capacity to achieve such outcomes within the regions of the world that confront these problems most sharply is a significant challenge. Aid policy can play an Important role in this respect – for example, by supporting capacity building through investment in local institutions such as universities rather than funnelling aid money back into donor countries through consultancies.

The scientific dominance of the global north is every bit as disempowering and threatening as post-colonial political domination.

For countries in the developing world, capacity building in research is critical to supporting their own countries. Another good example of this is found in the High Ambition Pacific coalition led by the Marshall Islands which secured significant support from European countries and elsewhere, in their campaign for a 1.5 degrees emissions target at the COP21 meeting in Paris in 2015.

Science-policy-advocacy alliance

This coalition was a good example of a science-policy-advocacy alliance which did not come from the global north.

Scientific as well as policy collaborations between the global south and the global north are certainly possible but it also the case that scientific research and intervention in the countries of the south from the outside can very easily reinforce the political domination that politicians and policy-makers from the south so often experience in international forums and through the aid policies bestowed upon them from outside.

The aggressive assertion of the privileges of Western science to do research in developing countries at the expense of building local capacity demonstrates another side of this post-colonial experience. It is impossible to credibly talk of “giving voice to the ‘disadvantaged’ and ‘vulnerable’” where the research practices of outside researchers and their institutions cripple the ability of local researchers to speak.

Yet, researchers in the Pacific are more effectively operating at the cutting-edge of the science-policy interface than many outside the region may understand or recognise.

In our own case at USP, genuine collaboration across the boundaries of south and north have been possible but just as our leaders and our communities have had to fight against patronising notions of “vulnerability” our scientific need is to build our own capacity to effectively engage with the priorities of our own region and its people. We aim to build a scientific and research capacity that is neither dominated by or exploited from outside.

So, in summary, the tensions that have traditionally been used to characterise the science-policy interface greatly oversimplify the reality. They oversimplify it at an abstract level by whether by characterising science as disinterested or by characterising the aim of policy-makers to rational and evidence-based.

They also oversimplify the relationships within and between scientific communities, ignoring the social interests and power structures that serve the continuation, whether intentionally or not, of post-colonial domination, restricting opportunities to build scientific capacity which enables the achievement of locally determined priorities.

Professor Derrick Armstrong is deputy vice-chancellor (research, innovation and international) at the Suva-based University of the South Pacific. This was a presentation made at the concluding “creative tension” panel at the DevNet 2018 “Disruption and Renewal” conference in Christchurch, New Zealand, last week.