A trailer for the controversial Anas investigation into corruption by Ghana’s judiciary. Video: AnanseGH TV

BOOKS: By David Robie

The Ghanaian investigative journalist summed up the mood among some 1500 media people with the beaded face veil rather well—a facial security screen symbolising both the safety of the reporter and his sources. But this was no empty gesture. It is characteristic of the man who has captured judges on tape allegedly taking bribes.

As the result of his celebrated documentary, Ghana in the Eyes of God: Epic of Injustice, more than 30 judges and 170 judicial officers were implicated in Ghana’s biggest corruption scandal.

On the same day that investigator Anas Aremeyaw Anas took the stage in his trademark mask at the World Press Freedom Day conference in Jakarta on 3 May 2017, a new book was being launched with the spotlight on wide-ranging research into the safety of journalists after many years of reporters being killed with impunity.

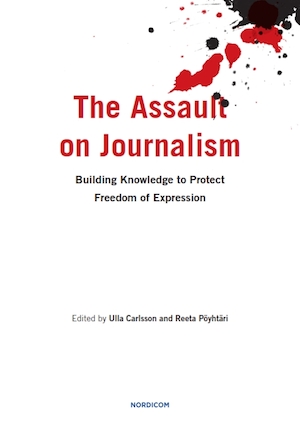

The Assault on Journalism: Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression is a diverse collection of empirical and theoretical papers presented at a parallel research conference at WPFD2016 in Helsinki, Finland.

The Assault on Journalism: Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression is a diverse collection of empirical and theoretical papers presented at a parallel research conference at WPFD2016 in Helsinki, Finland.

The book is divided into four main parts: 1. The Status of Safety of Journalists; 2. The Way Forward (this would have been better placed as the last section before the appendices); and 3. Research, concluding with three chapters on foreign correspondents and local journalists, Pakistani freedoms (or rather lack of them) and Nigerian digital safety.

It also republishes the UNESCO 2016 report Time to Break the Cycle of Violence Against Journalists and the UN safety action plan as the fourth part. However, there is a need for a “rounding off” chapter, which could actually have been Jackie Harrison’s “Setting a New Research Agenda”.

Keynote Helsinki address

Professor Simon Cottle’s introduction, “Journalist Killings and the Responsibility to Report”, was the keynote academic address in Helsinki. He cites figures compiled by the International News Safety Institute (INSI) indicating that around the world 111 media workers were killed in 2016 and 115 the following year. He also cites a Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) figure showing 2012 journalists being killed since 1992.

“Many of these deaths go largely unnoticed and unreported in the world’s media,” Cottle notes (p. 21). He also points to the deaths of American journalist Marie Colvin (wrongly named as Mary in the book)—described by many of her peers as ‘the greatest war correspondent of her generation’—and French photographer Rémi Ochlok in a bombardment of the Baba Amro district in the Syrian city of Homs on 22 February 2012 (Conroy, 2013).

Homs was earlier this year recaptured by the Assad regime. While admitting that high-profile deaths such these “remind us of the terrible price that can be paid by Western correspondents and photojournalists” when reporting conflict, they are not an accurate representation of journalist killings around the globe.

Data collected by world media freedom monitoring agencies show that most journalist killings and incidents of intimidation actually target local and “indigenous” journalists. The reason is simple, according to Cottle:

“Following the end of the Cold War, the world’s political tectonic plates moved and fragmented, creating a situation of multiple power plays and shifting political actors that no longer align in a predictable, bipolar world of allegiances.” (p. 22)

Cottle argues for a greater mandate for the safeguarding of journalists in their responsibilities to report from dangerous places. “In violent times, [the protection] cannot therefore be simply seen as a matter to do with ‘journalists’ or, even more broadly, as simply about ‘journalism’.”

Genesis of journalism safety

Guy Berger, director of UNESCO’s Freedom of Expression division in Paris, explores the genesis of journalism safety issues and why they have become critical to the global free media agenda. Acknowledging that the end of the Cold War enabled a fresh focus on safety issues, he says “it was the harsh reality that drove safety to the top of the agenda” (p. 36).

Outlining the objectives of the UN plan of action, especially against extrajudicial killings, Berger argues the need for strategic partnerships with a gender-sensitive approach. Berger, former head of journalism at Rhodes University in South Africa, also acknowledges the “growing positive response from academia” since 2014 with research programmes and initiatives on the topic of safety and impunity.

This academic response was reflected again at WPFD2017 in Jakarta, although the two days of research papers are more likely to be the basis of commentary and analytical pieces in social media and popular online outlets rather another book at this stage.

Two of the more interesting chapters are “Gendering War and Peace Journalism” by Berit von der Lippe and Rune Ottosen and “Collaboration is the Future” by Thomas Hanitzsch. While acknowledging that the storytelling domination of war and glory through the “masculinised memory” of males in powerful positions and male reporters has been challenged by a growing “women’s presence” among political leaders and war-reporting media, the hegemonic discourse largely remains intact.

“War reporting has been overrepresented by elite sources like politicians, high ranking military officers and state officials. These elite sources are collectively dominated by men and it will require more than more women journalists to change this male hegemony.” (p. 63)

Von der Lippe and Ottosen offer a useful encapsulation of Galtung’s model of “war journalism” and “peace journalism”: “War journalism is violence-oriented, propaganda-oriented, elite-oriented and victory-oriented; peace journalism is people oriented … focuses on the victims (often civilian casualties) and thus gives voice to the voiceless”.

It is also truth-oriented. However, the authors are critical of notions of liberal feminism being assumed to offer better or more peace journalism.

‘Coordinated cooperation’ model

As they note, women in general do not share some “gender-specific style of … journalistic philosophy”. Hanitzsch shares his “coordinated cooperation model” on international

collaborative research experience, particularly with the 10-year-old Worlds of Journalism Study involving 27,500 journalists in 67 countries. He makes a plea for wider adoption of this approach to collaborative research in the “network era”.

Overall, this is a very timely and valuable volume for journalism educators and researchers—and also for journalists and journalism safety advocates themselves. Nordicom, UNESCO and IAMCR deserve commendation for bringing this research collection to fruition.

The Assault on Journalism: Building Knowledge to Protect Freedom of Expression, edited by Ulla Carlsson and Reeta Pöyhtäri. Gothenburg, Sweden: Nordic Information Centre for Media and Communication Research (Nordicom). 2017. 363 pages. ISBN 9789187957505

This review was published originally in Pacific Journalism Review.

References

Anas Aremeyaw Anas (2015). Ghana in the Eyes of God; Epic of Injustice [Documentary]. Retrieved from www.youtube.com/watch?v=0S4rgAbYaZc

Conroy, P. (2013). Under the wire: Marie Colvin’s final assignment. New York: Weinstein Books.