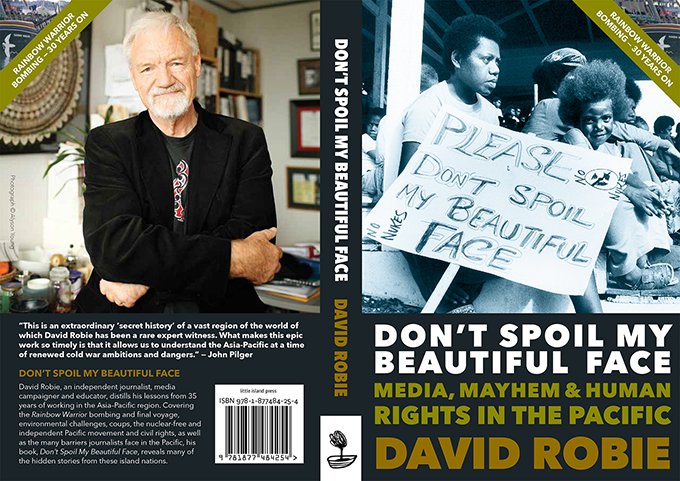

Dr Shailendra Singh reviews a new edition of Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face.

Above all, David Robie’s Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face: Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific is a damning indictment of the parlous state of affairs in parts of this region.

The book is also a telling account of the continuous failure of leadership on a fairly grand scale, with ordinary people bearing the brunt of it.

Dr Robie, professor of journalism at the Auckland University of Technology and director of the Pacific Media Centre, deals with the vital issues of environmental degradation, media censorship, social chaos and human suffering (largely caused by bad governance), various types of violent and nonviolent conflicts, and colonialism and neocolonialism.

Allegedly apathetic international and local media also attract some flak. Robie, who has a long record of service in the Pacific Islands, laments that a region with so much promise due to its relative tranquility, natural beauty, and richness of culture has been in such a prolonged state of decline, despite the postindependence optimisms.

That tranquility has been shattered by coups, civil uprisings, and corruption; the region’s pristine environments damaged by nuclear testing, wanton resource exploitation, and the spectre of climate change; and indigenous cultures threatened by the twin forces of neocolonialism and neoliberal economics.

These adversities are superimposed on growing incidences of human rights abuses and draconian media legislation in some countries.

The looming threats of global warming and sea-level rise only complicate matters.

Robie has been reporting these trends in the Asia-Pacific region since the 1980s, both as a journalist and as a media educator, covering self-determination for indigenous minorities in New Caledonia, the struggles in Timor-Leste and West Papua, the Bougainville rebellion, nuclear testing in French Polynesia and the Marshall Islands, and the ethnically motivated coups in Fiji.

Documented conflicts

Some of these conflicts are documented in his earlier books: Blood on the Banner (1980) highlighted indigenous Pacific Islanders’ struggle against the remnants of colonialism, while Tu Galala: Social Change in the Pacific (1992) depicted a continuing battle against environmental catastrophe, communal unrest, growing militarisation, ongoing poverty, colonialism, and neocolonialism.

In Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face, Robie reproduces some of his previous writings as a yardstick and a backdrop for deeper insights into the Pacific’s seemingly intractable problems. Reflecting on his two-and-a-half decades of Asia-Pacific coverage, Robie intones, “Sadly, not a lot has changed” (page 6).

He adds, “Political independence has not necessarily rid the Pacific of the problems that it faces, and in many cases, Pacific political leaders are themselves part of the problem” (27). One of the more startling statistics, at least for the uninitiated, is the deaths of an estimated 120,000 Pacific Islanders in various disputes over the past quarter-century, plus another 200,000 when Timor-Leste is included (311).

If the narrative sounds depressing, it is regrettably all too predictable: long-term ethnic and political tensions coupled with low growth rates and underdevelopment are usually fodder for violent conflict in fragile states (see Securing a Peaceful Pacific, by John Henderson and Greg Watson [2005]).

Robie is forthright in putting the blame for these serious issues squarely on various corrupt Pacific Island leaders, whom he views as having been part of the problem for far too long. But it is not only rogue Pacific Island leaders who are causing problems.

Robie also faults leaders from developed countries for their inaction in the face of what he describes as a litany of tortures, murders, exploitation, rapes, military raids, and arbitrary arrests. Most affected is West Papua, where the brutal repression of the native Melanesians by the Indonesian security services is well documented.

The book reminds us why the Pacific is still struggling despite copious amounts of bilateral aid over the decades. It is in the interest of nuclear powers France and the United States to keep their territories in a dependent state in order to further their own military, economic, and geopolitical ambitions.

Exploitation ‘normalised’?

The question is whether the exploitation of Island countries by economically and militarily powerful nations has become normalised. Recently, Australia and New Zealand remained unmoved in the face of Pacific Islander anger over the two countries’ apparent intransigence regarding a joint proposal by Pacific Island nations for a tougher global target on greenhouse gas emissions. Is the world resigned to the bullying and maltreatment of Pacific Island nations by the bigger powers?

Robie does not hide his disappointment with what he sees as the media’s failure to tackle these crucial issues.

He feels that the international media ignore or underreport major issues, such as Indonesian repression of West Papua and the assassination of journalists in the Philippines. In his eyes, Australian media failed to sufficiently probe their country’s 2006 security treaty with Indonesia. Robie insists that the treaty led to Australia’s overt repression of pro-independence Papuan activists.

To be fair to the media, the Indonesian government has banned foreign journalists from West Papua for years. However, Robie argues that the problem goes deeper. He links it to the media’s commercially driven priorities, which he feels supersede social, humanitarian, and public-interest obligations.

Under this journalistic framework, West Papua would be deemed too costly an assignment for sustained coverage, financially and politically.

Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face tries to prod the media’s conscience by highlighting the suffering in the region. Robie advocates a new, more thorough, considered, and inclusive reporting approach, which he describes as “critical development journalism.”

This proposed framework sources grassroots rather than just elite views, emphasises conflict resolution, promotes human rights, and supports development (325–330).

Empowered media

Robie’s views are consistent with a growing recognition among some policy makers that an empowered media could play an important role in regional development, especially in politically fragile Island societies. However, new ideas often face resistance.

As a result of challenging the orthodoxy, Robie has attracted criticism from some traditionalists, who believe that concepts such as “peace journalism” contravene media objectivity, what with Bainimarama’s military-backed government in Fiji touting its version of “journalism of hope,” fueling suspicions about government control of the media under the guises of stability and development.

Robie is adamant that critical development journalism is not soft journalism, and neither would it pander to political slogans such as “cultural sensitivity,” which he sees as a cover-up for abuse of power.

To the contrary, Robie envisions an approach based on a greater level of intensive journalism focused on exposing the truth, reporting on alternatives, and offering solutions. Robie’s central thesis is that the Pacific is caught in a vicious cycle of conflicts and underdevelopment.

Traditional subsistence lifestyles have been under sustained pressure from globalisation and other forces. The media are duty-bound to keep track of these trends and draw attention to them, but their response has largely been inadequate.

Robie is calling for a new media strategy, based on greater journalistic effort, commitment, and foresight. Some may question whether such a new direction is even possible, given media’s entrenched, deadline-driven, profit-focused economic model.

These ideological arguments aside, the post–Cold War trend of mayhem in the Pacific demands investigation into the media-politics-conflict nexus in the Pacific context. Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face seeks to fill this gap.

Dr Shailendra Singh is a senior lecturer and coordinator of journalism at the University of the South Pacific. This review was commissioned by The Contemporary Pacific journal and has been republished with permission.

- Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face: Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific, by David Robie. Auckland: Little Island Press. [Second edition.] ISBN 978-1-8774- 8425-4; 363 pages, maps, notes, bibliography, index. Paper, NZ$40.00.