As New Caledonia’s November 4 referendum on independence approaches, both pro and anti-independence groups are ramping up their campaigns. But, as Michael Andrew reports, some groups are choosing not to participate, arguing that the referendum is “unfair and dishonest”.

For many Kanaks, the upcoming independence referendum is a chance to reclaim control of New Caledonia, or “Kanaky”, and establish a new independent nation in the Pacific.

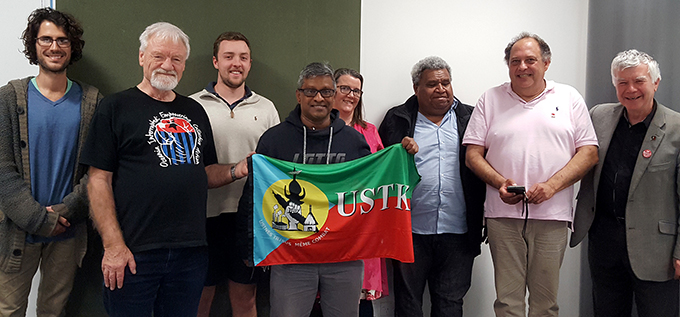

For pro-independence labour organisation USTKE (Union of Kanak and Exploited Workers), however, the November 4 referendum is undemocratic and should be treated as a non-event.

On a visit to New Zealand this week, Leonard Wahmetu, general secretary of the mines and metals section of the USTKE, said his organisation and its political arm, the Labour Party, would not be participating in the referendum as it had been tailored to favour an outcome of remaining with France.

READ MORE: Lee Duffield’s Asia Pacific Report series on New Caledonia and the referendum

Referring to the period preceding the 1988 Matignon accord – the first step in France’s promise of eventual sovereignty for the Kanaks – Wahmetu said that the demographics of Kanaky were significantly altered when the French government encouraged mass migration from mainland France, eroding the Kanak’s voting majority in subsequent referenda.

Although participation in the November 4 voting excludes anyone who came to live in the territory after 1998, Wahmetu argued that the referendum’s credibility had been comprised by those historical events.

“The vote is not sincere, it is not honest, it is not true,” he said.

Discrepancies in the roll

The referendum voting roll has also come under scrutiny, with the USTKE and other pro-independence parties claiming many Kanaks have not been included.

According to an RNZ Pacific report, pro-independence groups feel Kanaks should be automatically included on the roll, but the electoral law states that voters must register to cast a ballot.

Wahemtu argued that the vague and complex administrative process makes registration difficult for Kanaks, many of whom can’t access the documents to prove their eligibility.

According to Australian academic and journalist Dr Lee Duffield, a research associate of the Pacific Media Centre, this lack of familiarity with the Western democratic process may also be a reason why many Kanaks believe the referendum is stacked against them.

“French conservative parties and Caldoche interests are the most at home with persuasive negotiation, lobbying, campaigning and advertising. The Kanak system is more community based and not so at home with modern-day politicking,” he said.

However, he did stress that the French government had made access to the roll very open for Kanaks, citing an instance where a Kanak who had been living abroad for a long time was allowed to enrol.

Despite its stance of non-participation, the USTKE is staunchly pro-independence and has fought emphatically for Kanak workers’ rights since the early 1980s, when it was a key component of the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS).

1980s protest action

During that period, anti-colonial sentiment was high among Kanaks, mainly due to France’s harsh policies of military action and assassinations to repress the indépendentiste movement. Violent protest in response was not uncommon.

After the tragic 1988 massacre on Ouvéa Island where 19 FLNKS militants were killed after taking a group of gendarmes (district police) hostage, the French government was forced to seriously consider the Kanaks quest for independence and the negotiation of the Matignon Accord ensued. After having signed it with the FLNKS, the USTKE detached from the FLNKS in respect of the separation of trade unionism and politics.

It continued its campaigning for Kanak workers’ rights alongside the Confederation of Labour (CGT), the largest workers’ union in France.

While the CGT supports the indépendentiste movement, it respects the USTKE’s decision not to participate in the referendum.

CGT’s Asia Pacific director of the international department, Sylvain Goldstein, explained that regardless of the referendum, the aim of the USTKE was not to evict the French, but rather achieve a more inclusive and prosperous society.

“There is not a will to end relations with France, not at all. It’s more to rebalance the rights and consider everything that needs to be considered for a better situation and open up to Pacific neighbours,” Goldstein said.

For the USTKE, a better situation would also include fairer representation and employment for Kanaks, especially in the lucrative nickel mining industry.

Promises eroded

Despite the industry being one of the largest in the world, Kanaks are grossly under-represented; something that Leonard Wahmetu said went against promises laid out in the Matignon Accord.

“There was an agreement that a lot more Kanak people will be trained to have more responsibility. Now only 50 are involved in the mining because they give the training to the people from mainland France,” he said.

Yet even skills and expertise are often not enough to guarantee employment in an industry that Wahmetu claims, is rife with discrimination.

“Even if the young people are well trained they cannot find a job because they are Kanak,” he said.

Environmental protection is another key aim of the USTKE, which would see mining companies and other multinationals held to account for their impact on Kanaky’s natural resources.

According to Sylvain Goldstein, unauthorised expansion by mining companies can imperil the natural environment, leading to conflict with Kanak tribes who have a duty to protect the land.

Protester blockade

This has occurred most recently in the town of Kouaoua, where protesters have blockaded the SLN mining company in an effort to protect endemic oak trees. The mine has since been shut down, reports RNZ.

For Leonard Wahmetu, this kind of activism is exactly what’s needed to exact change in a system where the democratic processes are not fair or impartial.

While the USTKE and the Labour Party will still be working in the political arena for policy changes and fairer electoral rolls, he stresses the importance of strong action.

“Political pressure and protest go together. We can’t just talk in the office, we must protest out in the field,” he said.

“Without this we wouldn’t be heard.”

Michael Andrew is a student journalist on the Postgraduate Diploma in Communication Studies (Journalism) reporting on the Asia-Pacific Journalism course at AUT University.