By Rahul Bhattarai

Military forces on peacekeeping duties often face dilemmas that are difficult to resolve, says a retired colonel who is now an education consultant.

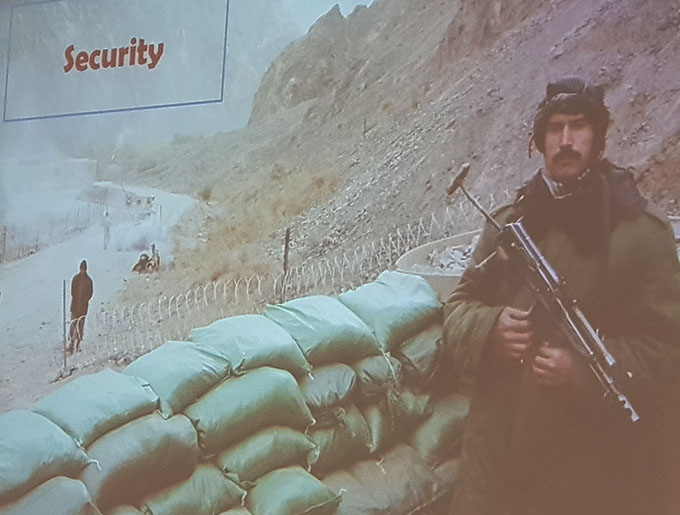

Colonel Richard Hall, who retired from the British Army after 25 years’ service, peacekeeping roles in several countries, and led a New Zealand mission to Afghanistan in 2008/9, told an audience at Auckland University of Technology he had faced a challenge when a local tribal chief asked for security for young schoolchildren.

The chief was running a small school where he was teaching young children, but he was getting death threats from the Taliban who wanted him to stop teaching.

Colonel Hall had to decline the request.

“Sadly, I couldn’t,” he said.

This kind of dilemma was rather common for military officers, especially when they were engaged in an operation with limited military resources or mandate that did not allow such activity, said Hall.

He was speaking at a public event organised by the Auckland branch of the United Nations Association of New Zealand on the theme “peacekeeping and the use of force”.

‘Victors’ peace’

Hall said World War 2 was a “victors’ peace” and the United Nations Charter was heavily influenced by the Allies who had won the war – China, France, United Kingdom, United States and the Soviet Union.

They “preserved” their power through enabling a veto in the Security Council. That gave them the ability to influence their “common interest”.

“It wasn’t long before the political divide between the East and West came out,” he said.

This was when the permanent members were often in complete disagreement with each other.

The common interest became difficult, and often it led to the creation of “mandates” by the UN.

“Those [mandates] were a compromise, they were weakly worded to avoid a veto,” Hall said.

This was a major concern as it caused lots of difficulties for the people on the ground, including confusion over the role of UN peacekeeping force.

The public generally confused the UN’s role with providing security to the host country, but that was incorrect.

Impartial role

The key aspect of peacekeeping operation was the UN being totally impartial.

It was not about taking sides – except for two exceptions; the Korean War in 1950 and the invasion of Iraq in 1990. However, these were examples of peace enforcement operations (under chapter 7 of the Charter) as distinct from peacekeeping operations.

The UN tried to bring various sides of a conflict together through a political process to reach a peace agreement – while the military worked in the background facilitating the process.

UN Charter’s chapter six is devoted to the peaceful settlements of disputes.

“Political negotiation between warring parties were the preeminent way of resolving conflicts”, Hall said.

Some roles for the military in peacekeeping tended to be completely unarmed or lightly armed troops doing a “couple of things”.

Hall said the UN military might be observers ensuring there was going to be a ceasefire agreement, or they might be creating a buffer zone between warring factions to prevent the conflict reigniting due to breach of a ceasefire.

Health impact

UN peacekeeping soldiers also suffered seriously from post-traumatic stress disorder as they were not allowed to intervene.

According to the United Nations (UN) Principles of Peacekeeping, there are three basic principles that set UN peacekeeping operations apart as a tool for maintaining international peace and security – consent of the parties, impartiality and non-use of force except in self-defence, and defence of the mandate.

UN peacekeeping forces were not allowed to engage in any kind of offensive, unless it is for self-defence which created a huge problem for their mental well-being, Hall said.

Soldiers witness “killing and raping” and they could not do anything about it and that caused more psychological distress.

Hall said that if the public did not support the mission, that was demoralising for soldiers.

“They feel they have been committed to an operation and there is no political, moral support from the government of the day and also the general population,” he said.

Responding to a question from the audience, Hall said: “Although not a peacekeeping operation, an example of a lack of support was the Vietnam War: the New Zealand soldiers experienced the trauma of war and on their return were badly let down by the government and public.

“It wasn’t their fault that they were there, they were fulfilling a commitment made the New Zealand government of the day.”

Hall has been decorated with the New Zealand Order of Merit and has had a distinguished military career with service in Bosnia, Cyprus, Kosovo, Middle East and Northern Ireland as well as Afghanistan.

He was seconded to the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office to establish regional peacekeeping centres in Africa, working extensively with local military, politicians and NGOs.

Hall’s book A Long Road to Progress: Dispatches from a Kiwi Commander in Afghanistan is an autobiographical account.

Currently he is a senior educational consultant in the deputy vice-chancellor’s office at Auckland University of Technology.