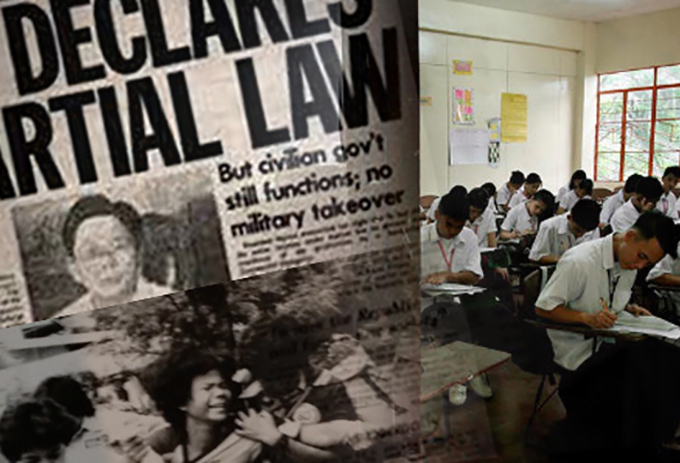

I give my column space today to my favorite communication man, Professor Crispin C. Maslog. A former journalist with Agence France-Presse, Cris was director of the Silliman School of Journalism and Communication when Martial Law was proclaimed in the Philippines 1972. He is now senior consultant, Asian Institute of Journalism and Communication, and chair of the board, Asian Media Information and Communication Center (AMIC) based in Manila.

While I was grappling with the horrible impositions of Martial Law when I was editor-in-chief of Philippine Panorama, I had to run to some safe, soul-restorative place on weekends outside the city. It was at the home of Cris and his wife scientist, Flor, on the University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB) campus that I found comfort and assurance that all will be well, that the tyrant Ferdinand Marcos and his family will be driven away from the land, and that democracy will be restored.

His article should remind us that Martial Law should never happen again – and the

perpetrators not be returned to seats of power. – Domini M. Torrevillas, The Philippine Star

By CRISPIN C. MASLOG in Manila

Somehow, today’s university student generation is not to blame for its Martial Law amnesia. These people were not yet born at the time Martial Law was proclaimed 44 years ago!

We, the older folks, are to blame. We did not teach them history properly – and I mean by we, mainly the Philippine government and the mass media who suffered the most under the Martial Law regime of Ferdinand Marcos.

Now that the surviving members of the Marcos family are active in politics again and pushing a revisionist version of Martial Law history, we are worried, to say the least.

So when I told students at Silliman’s College of Mass Communication recently about the abuses during Martial Law proclaimed by Marcos in 1972, they were aghast at what they heard. I told the group that before Martial Law was proclaimed in 1972, the Philippines went through hard times under Marcos’ two four-year terms from 1965 to 1973 – the years of discontent.

There was a dramatic increase in poverty during Marcos’ two elective terms, resulting in social unrest.

Yet Marcos wanted to extend his term, which he could not do legally because he was limited by the Constitution to two presidential terms ending in 1972. So he decided to suspend the Constitution and declare Martial Law on Sept. 21, 1972.

The first few years under Martial Law were peaceful and orderly. The average person liked that people were disciplined. But people were disciplined because they were afraid.

More corrupt

And soon after 1972, Marcos and his family became more corrupt because no one, especially the mass media, was free to criticise them. Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The next 14 years witnessed corruption unparalleled in Philippine history.

Instead of improving, the Philippine economy took a nosedive during the 14 years of Martial Law because of cronyism and economic plunder. Cronyism was an “economic system” where every major economic activity was controlled by the First Family, their relatives, or cronies.

This phenomenon was documented meticulously by Ricardo Manapat in his 615-page book, Some Are Smarter Than Others: The History of Marcos’ Crony Capitalism (Aletheia Publications, NY, 1991). The New York Times has reviewed the book as “impressively documented”.

Answering criticisms about relatives who became millionaires overnight during Martial Law, Madame Imelda is quoted to have replied: “My dear, there are always people who are just a little faster, more brilliant, more aggressive.”

The Manapat book is based on 11 years of research and writing and is the authoritative source of information on the economic plunder of the Philippines under Marcos. The title of the book is based on a famous quote from Madame Imelda.

The major cronies, as documented in Manapat’s book, were: Roberto Benedicto who controlled the sugar industry, Danding Cojuangco who monopolised the coconut industry, Antonio Floirendo who cornered the banana industry, and Hans Menzi who lorded over the mining and paper industries.

Cronyism meant giving loans to friends that had little or no collateral, whose corporations were undercapitalised. Marcos, family and his cronies used the national coffers, the resources of private banks, and even international loans from multinational banks for their business. Aid money from the US and Japan were placed at the disposal of Marcos’ money-making network.

Squandered loans

Until today we are still paying for these loans squandered by the Marcos regime.

The corruption reached such a massive scale that it took its toll on the Philippine economy and the lives of the average Filipino. By 1986, just before People Power I, the number of Filipinos living below the poverty line doubled from 18 million in 1965 to 35 million.

The history of this economic plunder is one of the blind spots in the minds of the Filipino millenials today. It worries me and my generation no end, that the son of Ferdinand Marcos is running for vice-president of the land, and be just a heartbeat away from the presidency.

If that happens, philosopher George Santayana may again be proven right when he said long ago that a people who do not remember their past are condemned to repeat it.

Domini M. Torrevillas is a columnist on The Philippine Star. One of her From The Stands columns this month was devoted to this article by Professor Maslog and is republished here with the permission of the author. The Philippines presidential election is due on Monday, May 9.