SPECIAL REPORT: Islands Business in Suva

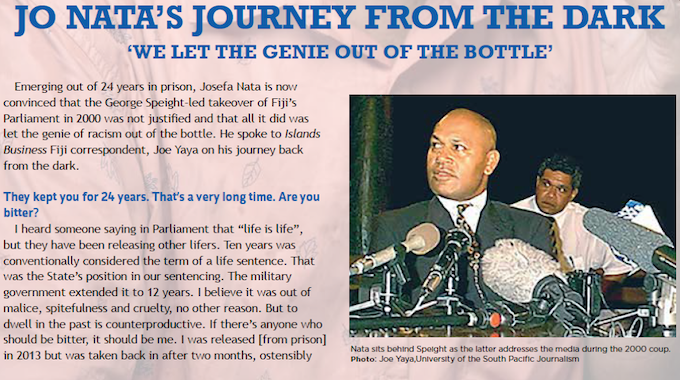

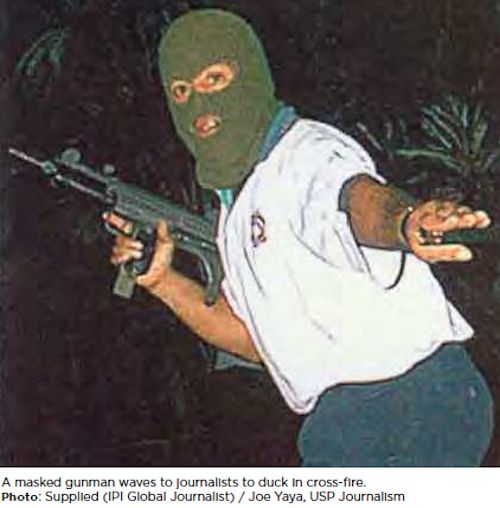

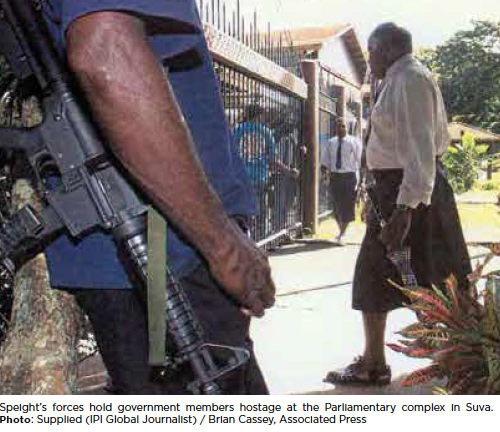

Today is the 24th anniversary of renegade and failed businessman George Speight’s coup in 2000 Fiji. The elected coalition government headed by Mahendra Chaudhry, the first and only Indo-Fijian prime minister of Fiji, was held hostage at gunpoint for 56 days in the country’s new Parliament by Speight’s rebel gunmen in a putsch that shook the Pacific and the world.

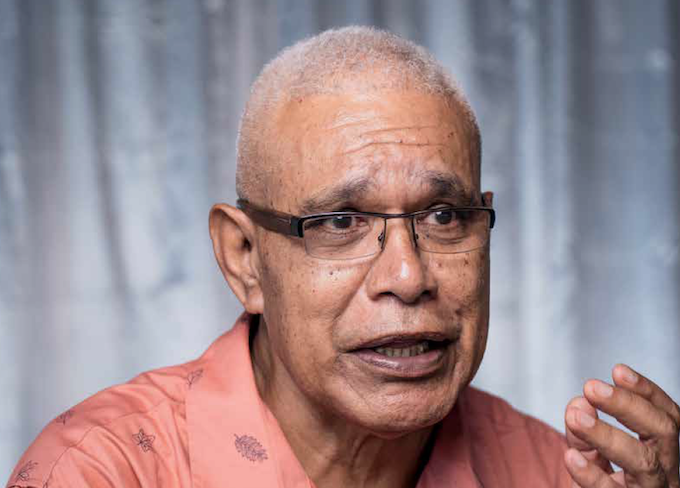

Emerging recently from almost 24 years in prison, former investigative journalist and publisher Josefa Nata — Speight’s “media minder” — is now convinced that the takeover of Fiji’s Parliament on 19 May 2000 was not justified.

He believes that all it did was let the “genie of racism” out of the bottle.

- READ MORE: Coup coup land: the press and the putsch in Fiji – David Robie

- FIJI: I was just PR consultant — Joe Nata

- USP 2000 coup student journalism archive

He spoke to Islands Business Fiji correspondent, Joe Yaya on his journey back from the dark.

The Fiji government kept you in jail for 24 years [for your media role in the coup]. That’s a very long time. Are you bitter?

I heard someone saying in Parliament that “life is life”, but they have been releasing other lifers. Ten years was conventionally considered the term of a life sentence. That was the State’s position in our sentencing. The military government extended it to 12 years. I believe it was out of malice, spitefulness and cruelty — no other reason. But to dwell in the past is counterproductive.

If there’s anyone who should be bitter, it should be me. I was released [from prison] in 2013 but was taken back in after two months, ostensibly to normalise my release papers. That government did not release me. I stayed in prison for another 10 years.

To be bitter is to allow those who hurt you to live rent free in your mind. They have moved on, probably still rejoicing in that we have suffered that long. I have forgiven them, so move on I must.

Time is not on my side. I have set myself a timeline and a to-do list for the next five years.

What are some of those things?

Since I came out, I have been busy laying the groundwork for a community rehabilitation project for ex-offenders, released prisoners, street kids and at-risk people in the law-and-order space. We are in the process of securing a piece of land, around 40 ha to set up a rehabilitation farm. A half-way house of a sort.

You can’t have it in the city. It would be like having the cat to watch over the fish. There is too much temptation. These are vulnerable people who will just relapse. They’re put in an environment where they are shielded from the lures of the world and be guided to be productive and contributing members of society.

It will be for a period of up to six months; in exceptional cases, 12 months where they will learn living off the land. With largely little education, the best opportunity for these people, and only real hope, is in the land.

Most of these at-risk people are [indigenous] Fijians. Although all native land are held by the mataqali, each family has a patch which is the “kanakana”. We will equip them and settle them in their villages. We will liaise with the family and the village.

Apart from farming, these young men and women will be taught basic life skills, social skills, savings, budgeting. When we settle them in the villages and communities, we will also use the opportunity to create the awareness that crime does not pay, that there is a better life than crime and prison, and that prison is a waste of a potentially productive life.

Are you comfortable with talking about how exactly you got involved with Speight?

The bulk of it will come out in the book that I’m working on, but it was not planned. It was something that happened on the day.

You said that when they saw you, they roped you in?

Yes. But there were communications with me the night prior. I basically said, “piss off”.

So then, what made you go to Parliament eventually? Curiosity?

No. I got a call from Parliament. You see, we were part of the government coalition at that time. We were part of the Fijian Association Party (led by the late Adi Kuini Speed). The Fiji Labour Party was our main coalition partner, and then there was the Christian Alliance. And you may recall or maybe not, there was a split in the Fijian Association [Party] and there were two factions. I was in the faction that thought that we should not go into coalition.

There was an ideological reason for the split [because the party had campaigned on behalf of iTaukei voters] but then again, there were some members who came with us only because they were not given seats in Cabinet.

Because your voters had given you a certain mandate?

Well, we were campaigning on the [indigenous] Fijian manifesto and to go into the [coalition] complicated things. Mine was more a principled position because we were a [indigenous] Fijian party and all those people went in on [indigenous] Fijian votes. And then, here we are, going into [a coalition with the Fiji Labour Party] and people probably

accused us of being opportunists.

But the Christian Alliance was a coalition partner with Labour before they went into the election in the same way that the People’s Alliance and National Federation Party were coalition partners before they got into [government], whereas with us, it was more like SODELPA (Social Democratic Liberal Party).

So, did you feel that the rights of indigenous Fijians were under threat from the Coalition government of then Prime Minister Mahendra Chaudhry?

Perhaps if Chaudhry was allowed to carry on, it could have been good for [indigenous] Fijians. I remember the late President and Tui Nayau [Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara] . . . in a few conversations I had with him, he said it [Labour Party] should be allowed to . . . [carry on].

Did you think at that time that the news media gave Chaudhry enough space for him to address the fears of the iTaukei people about what he was trying to do, especially for example, through the Land Use Commission?

I think the Fijians saw what he was doing and that probably exacerbated or heightened the concerns of [indigenous] Fijians and if you remember, he gave Indian cane farmers certain financial privileges.

The F$10,000 grants to move from Labasa, when the ALTA (Agricultural Landlord and Tenants Act) leases expired. Are you talking about that?

I can’t remember the exact details of the financial assistance but when they [Labour Party] were questioned, they said, “No, there were some Fijian farmers too”. There were also iTaukei farmers but if you read in between the lines, there were like 50 Indian farmers and one Fijian farmer.

Was there enough media coverage for the rural population to understand that it was not a one-sided ethnic policy?

Because there were also iTaukei farmers involved. Yes, and I think when you try and pull the wool over other people, that’s when they feel that they have been hoodwinked. But going back to your question of whether Chaudhry was given fair media coverage, I was no longer in the mainstream media at that time. I had moved on.

But the politicians have their views and they’ll feel that they have been done badly by the media. But that’s democracy. That’s the way things worked out.

Pacific journalism educator, David Robie, in a paper in 2001, made some observations about the way the local media reported the Speight takeover. He said, “In the early weeks of the insurrection, the media enjoyed an unusually close relationship with Speight and the hostage takers.”

He went on to say that at times, there was “strong sympathy among some journalists for the cause, even among senior editorial executives”.

David Robie is an incisive and perceptive old-school journalist who has a proper understanding of issues and I do not take issue with his opinion. And I think there is some validity. But you see, I was on the other [Speight’s] side. And it was part of my job at that time to swing that perception from the media.

Did you identify with “the cause” and did you think it was legitimate?

Let me tell you in hindsight, that the coup was not justified

and that is after a lot of reflection. It was not justified and

could never be justified.

When did you come to that conclusion?

It was after the period in Parliament and after things were resolved and then Parliament was vacated, I took a drive around town and I saw the devastation in Suva. This was a couple of months later. I didn’t realise the extent of the damage and I remember telling myself, “Oh my god, what have we done? What have we done?”

And I realised that we probably have let the genie out of the bottle and it scared me [that] it only takes a small thing like this to unleash this pentup emotion that is in the people. Of course, a lot of looting was [by] opportunists because at that time, the people who

were supporting the cause were all in Parliament. They had all marched to Parliament.

So, who did the looting in town? I’m not excusing that. I’m just trying to put some perspective. And of course, we saw pictures, which was really, very sad . . . of mothers, women, carrying trolleys [of loot] up the hill, past the [Colonial War Memorial] hospital.

So, what was Speight’s primary motivation?

Well, George will, I’m sure, have the opportunity at some point to tell the world what his position was. But he was never the main player. He was ditched with the baby on his laps.

So, there were people So, there were people behind him. He was the man of the moment. He was the one facing the cameras.

Given your education, training, experience in journalism, what kind of lens were you viewing this whole thing from?

Well, let’s put it this way. I got a call from Parliament. I said, “No, I’m not coming down.” And then they called again.

Basically, they did not know where they were going. I think what was supposed to have happened didn’t happen. So, I got another call, I got about three or four calls, maybe five. And then eventually, after two o’clock I went down to Parliament, because the person who called was a friend of mine and somebody who had shared our fortunes and misfortunes.

So, did you get swept away? What was going on inside your head?

I joined because at that point, I realised that these people needed help. I was not so much as for the cause, although there was this thing about what Chaudhry was doing. I also took that into account. But primarily because the call came [and] so I went.

And when I was finally called into the meeting, I walked in and I saw faces that I’d never seen before. And I started asking the questions, “Have you done this? Have you done that?”

And as I asked the questions, I was also suggesting solutions and then I just got dragged into it. The more I asked questions, the more I found out how much things were in disarray.

I just thought I’d do my bit [because] they were people who had taken over Parliament and they did not know where to go from there.

But you were driven by some nationalistic sentiments?

I am a [indigenous] Fijian. And everything that goes with that. I’m not infallible. But then again, I do not want to blow that trumpet.

Did the group see themselves as freedom fighters of some sort when you went into prison?

I’m not a freedom fighter. If they want to be called freedom fighters, that’s for them and I think some of them even portrayed themselves [that way]. But not me. I’m just an idiot who got sidetracked.

This personal journey that you’ve embarked on, what brought that about?

When I was in prison, I thought about this a lot. Because for me to come out of the bad place I was in — not physically, that I was in prison, but where my mind was — was to first accept the situation I was in and take responsibility. That’s when the healing started to take place.

And then I thought that I should write to people that I’ve hurt. I wrote about 200 letters from prison to anybody I thought I had hurt or harmed or betrayed. Groups, individuals, institutions, and families. I was surprised at the magnanimity of the people who received my letters.

I do not know where they all are now. I just sent it out. I was touched by a lot of the responses and I got a letter from the late [historian] Dr Brij Lal. l was so encouraged and I was so emotional when I read the letter. [It was] a very short letter and the kindness in the man to say that, “We will continue to talk when you come out of prison.”

There were also the mockers, the detractors, certain persons who said unkind things that, you know, “He’s been in prison and all of a sudden, he’s . . . “. That’s fine, I accepted all that as part of the package. You take the bad with the good.

I wrote to Mr Chaudhry and I had the opportunity to apologise to him personally when he came to visit in prison. And I want to continue this dialogue with Mr Chaudhry if he would like to.

Because if anything, I am among the reasons Fiji is in this current state of distrust and toxic political environment. If I can assist in bringing the nation together, it would be part of my atonement for my errors. For I have been an unprofitable, misguided individual who would like to do what I believe is my duty to put things right.

And I would work with anyone in the political spectrum, the communal leaders, the vanua and the faith organisations to bring that about.

I also did my traditional apology to my chiefly household of Vatuwaqa and the people of the vanua of Lau. I had invited the Lau Provincial Council to have its meeting at the Corrections Academy in Naboro. By that time, the arrangements had been confirmed for the Police Academy.

But the Roko gave us the farewell church service. I got my dear late sister, Pijila to organise the family. I presented the matanigasau to the then-Council Chairman, Ratu Tevita Uluilakeba (Roko Ului). It was a special moment, in front of all the delegates to the council meeting, the chiefly clan of the Vuanirewa, and Lauans who filled the two buses and

countless vehicles that made it to Naboro.

Our matanivanua (herald) was to make the tabua presentation. But I took it off him because I wanted Roko Ului and the people of Lau to hear my remorse from my mouth. It was very, very emotional. Very liberating. Cathartic.

Late last year, the Coalition government passed a motion in Parliament for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Do you support that?

Oh yes, I think everything I’ve been saying so far points that way.

Do you think it’ll help those that are still incarcerated to come out and speak about what happened in 2000?

Well, not only that but the important thing is [addressing] the general [racial] divide. If that’s where we should start, then we should start there. That’s how I’m looking at it — the bigger picture.

It’s not trying to manage the problems or issues of the last 24 years. People are still hurting from [the coups of] 1987. And what happened in 2006 — nothing has divided this country so much. Anybody who’s thought about this would want this to go beyond just solving the problem of 2000, excusing, and accusing and after that, there’s forgiveness and pardon.

That’s a small part. That too if it needs to happen. But after all that, I don’t want anybody to go to prison because of their participation or involvement in anything from 1987 to 2000. If they cooked the books later, while they were in government, then that’s a different

matter.

But I saw on TV, the weeping and the very public expression of pain of [the late, former Prime Minister, Laisenia] Qarase’s grandchildren when he was convicted and taken away [to prison]. It brought tears to my eyes. There is always a lump in my throat at the memory of my Heilala’s (elder of two daughters) last visit to [me in] Nukulau.

Hardly a word was spoken as we held each other, sobbing uncontrollably the whole time, except to say that Tiara (his sister) was not allowed by the officers at the naval base to come to say her goodbye.

That was very painful. I remember thinking that people can be cruel, especially when the girls explained that it was to be their last visit. Then the picture in my mind of Heilala sitting alone under the turret of the navy ship as she tried not to look back. I had asked her not to look back.

I deserved what I got. But not them. I would not wish the same things I went through on anyone else, not even those who were malicious towards me.

It is the family that suffers. The family are always the silent victims. It is the family that stands by you. They may not agree with what you did. Perhaps it is among the great gifts of God, that children forgive parents and love them still despite the betrayal, abandonment, and pain.

For I betrayed the two women I love most in the world. I betrayed ‘Ulukalala [son] who was born the same year I went to prison. I betrayed and brought shame to my family and my village of Waciwaci. I betrayed friends of all ethnicities and those who helped me in my chosen profession and later, in business.

I betrayed the people of Fiji. That betrayal was officially confirmed when the court judgment called me a traitor. I accepted that portrayal and have to live with it. The judges — at least one of them — even opined that I masterminded the whole thing. I have to decline that dubious honour. That belongs elsewhere.

This article by Joe Yaya is republished from last month’s Islands Business magazine cover story with the permission of editor Richard Naidu and Yaya. The photographs are from a 2000 edition of the International Press Institute’s Global Journalist magazine dedicated to the reporting of The University of the South Pacific’s student journalists. Joe Yaya was a member of the USP team at the time. The archive of the award-winning USP student coverage of the coup is here.