OBITUARY: By Giff Johnson, editor of the Marshall Islands Journal and RNZ Pacific correspondent

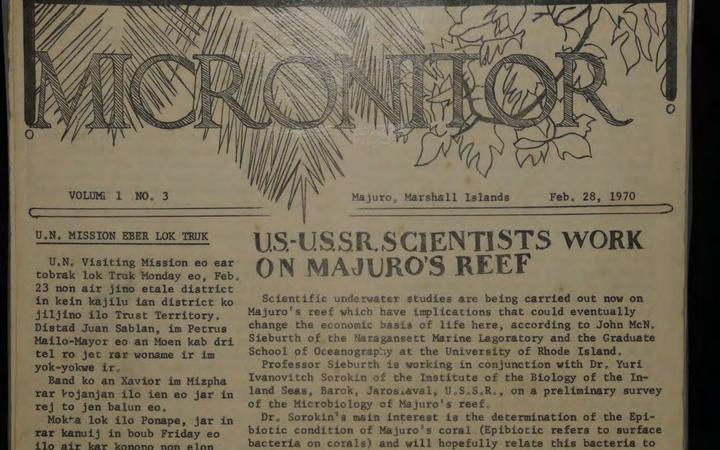

Micronitor News and Printing Company founder Joe Murphy moved the goal posts of freedom of press and freedom of expression in the Marshall Islands, a country that had virtually no tradition of either, by establishing an independent newspaper that today is the longest running weekly in the Micronesia region.

Murphy’s sharp intellect, fierce independence, vision for creating a community newspaper, bilingual language ability, and resilience in the face of adversity saw him navigate hurdles — including high tide waves that in 1979 washed printing presses out of the Micronitor building and into the street — to successfully establish a printing company and newspaper in the challenging business environment of 1970s Majuro.

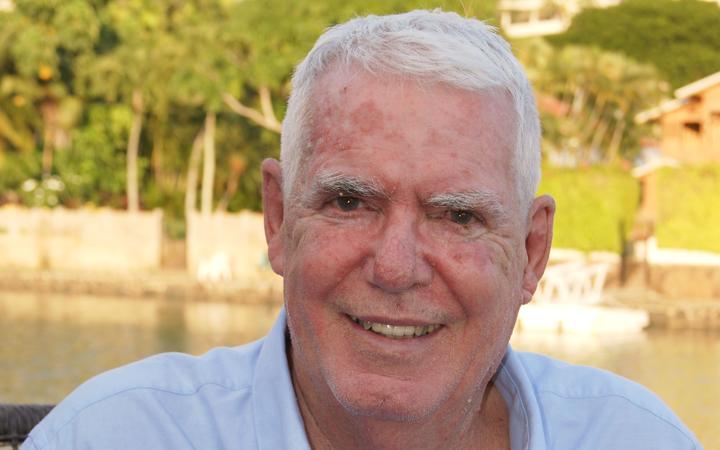

Murphy, who died at age 79 in the United States last week, was the original sceptic, who revelled in the politically incorrect.

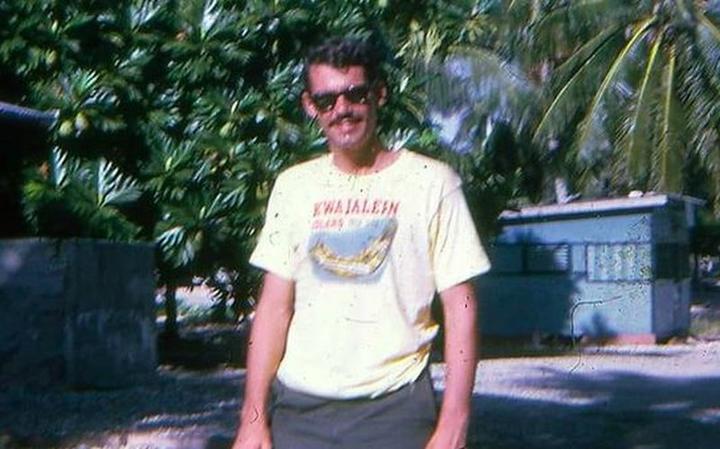

At 25, he arrived in the Marshall Islands capital Majuro in the mid-1960s and was dispatched by the Peace Corps to Ujelang, the atoll of the nuclear exiles from Enewetak bomb tests that was a textbook definition of the term “in the back of beyond.” A ship once a year, and no radio, TV, telephones or mail.

Still, Joe thrived as an elementary teacher, survived food shortages and hordes of rats, endearing him to a generation of Ujelang people as an honorary member of the exiled community.

After Ujelang, he wrapped up his two-year Peace Corps stint by taking over teaching an unruly urban centre public school class after the previous teacher walked out. He rewrote what he deemed boring curriculum and taught in military style, replete with chants in English.

These experiences in pre-1970s Marshall Islands fuelled his desire to return. After his Peace Corps tour, some time to travel the world, and a brief return to the US, Murphy headed back to Majuro.

No money, but a vision

He had no money to speak of, but he had a vision and he set out to make it happen.

“He was determined to start a newspaper written in both the English and Marshallese languages,” recalls fellow Peace Corps Volunteer Mike Malone, the co-founder with Murphy of what was initially known as Micronitor.

In late 1969, they began constructing a small newspaper building, mixing concrete and laying the foundation block-by-block with the help of a few friends.

Before the building was completed, however, they launched the Micronitor in 1970, printing from Malone’s house.

The Micronitor would be renamed later to the Micronesian Independent for a bit before finding its identity as the Marshall Islands Journal.

Writing in the Journal in 1999, Murphy commented: “The 30th anniversary of this publication is an event most of us who remember the humble beginnings of the Journal are surprised to see.

“February 13, 1970 was a Friday, an unlucky day to begin an enterprise by most reckonings, and the two guys who were spearheading the operation were Irish-extract alcohol aficionados with very little or no newspaper experience.

A worthy undertaking

“They also, between the two of them, had practically no money, and of course should never, had they any commonsense, even attempted such a worthy undertaking.

“But circumstances and time were on their side, and with all potential serious investors steering clear of such a dubious exercise they had the opportunity to make a great number of mistakes without an eager competitor ready and willing to capitalise on them.”

With Murphy at the helm, it wasn’t long before the Journal earned a reputation far beyond the shores of the tiny Pacific outpost of Majuro. Murphy encouraged local writers, and spiced the newspaper with pithy comment and attacks on US Trust Territory authorities and the Congress of Micronesia.

In the late 1980s and 1990s Murphy built two bars and restaurants, local-style places that appealed to Majuro residents as well as visitors. He also built the Backpacker Hotel, a modest cost accommodation that turned into a popular outpost for fisheries observers awaiting their next assignment at sea, low-budget journalists, environmentalists and assorted consultants.

“The first thing that people think about when it comes to my father is that he is a very successful businessman here in the Marshall Islands,” said his eldest daughter Rose Murphy, who manages the company today.

“But we need to remember him as someone who wanted to give the Republic of the Marshall Islands a voice.”

“To say Joe was a unique person is a large understatement,” said Health Secretary and former Peace Corps Volunteer Jack Niedenthal.

An icon with impact

“He was an icon and had a profound impact on our country because he fostered free speech and demanded that those in our government always be held publicly accountable for their actions.”

A plaque in his office defined his independent personality and his appreciation of the power of the press. It quoted the famous American journalist AJ Liebling: “Freedom of the press belongs to those who own one.” This was followed by a three-word comment: “I own one.” – Joe Murphy.

“He fought for freedom of speech and fought against discrimination,” said Rose Murphy. “Regardless of race, religion, and even status, he befriended people from all parts of the world and from all walks of life.”

In the mid-1990s, Joe Murphy created what became the justly famous motto of the Journal, the “world’s worst newspaper.” It was a reaction to the more politically correct mottos of other newspapers.

Those three words led to wide international media exposure. In 1994, the Boston Globe conducted a survey of the world’s worst newspapers, reviewing a batch of Journals Murphy mailed.

When the Globe reporter concluded that despite its claim, the Journal not only didn’t rank as the world’s worst newspaper it was “a first-class newspaper,” Murphy’s reaction was to say, “We must have sent you the wrong issues.”

Murphy knew the key to successful newspaper publishing was not how nicely or otherwise the newspaper was packaged, or if a photograph was in colour. The most important ingredient in any successful local newspaper is original content, intelligently and interestingly written.

‘Livened up’ the Journal

He did more than his fair share to liven up the Journal, from the time of its launch until poor health after 2019 prevented his engagement in the newspaper.

“My father experienced extreme hardships on Ujelang along with his adopted Marshallese family, the exiled people of Enewetak Atoll, who were moved to Ujelang to make way for US nuclear tests in the late 1940s,” said daughter Rose.

“He shared these hardships with his children to give them the perspective of being grateful for any little thing we had. If we had a broken shoe or little food, he shared with us this story.

“Our father, to us, is a symbol of resilience and gratitude. Be resilient in tough situations.”

From growing up among eight children of Irish immigrant parents in the United States to the austerity of Ujelang Atoll to the early days of establishing what would become the longest publishing weekly newspaper in the Micronesia region, Murphy was indeed a symbol of resilience and independence, able to navigate tough situations with alacrity.

“Democracy was able to establish a toehold, and then a firm grip, in the Western Pacific in part because of a handful of journalism pioneers who believed in the power of truth, particularly Joe Murphy on Majuro,” said veteran Pacific island journalist Floyd K Takeuchi.

“He had the courage to challenge the powers that be, including those of the chiefly kind, to be better, and to do better.

“People forget that for many years, the long-term future of the Marshall Islands Journal wasn’t a sure thing. With every issue of the weekly newspaper, Joe’s legacy is made firmer in the islands he so loved.”

Murphy is survived by his wife Thelma, by children Rose, Catherine “Katty,” John, Suzanne, Margaret “Peggy,” Molly, Fintan, Sam, Charles “Kainoa,” Colleen “Naki,” Patrick “Jojo”, Sean, Sylvia Zedkaia and Deardre Korean, and by 32 grandchildren.

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.