REVIEW: By Krishan Dutta

While the covid-19 pandemic’s relentless cyclone continues across the globe wreaking havoc on economies and social systems, this book sheds light on the adversarial reporting culture of the media, and how it impacts on racism and politicisation driving the coverage.

It explores the global response to the covid-19 pandemic, and the role of national and international media, and governments, in the initial coverage of the developing crisis.

With specific chapters written mostly by scholars living in these countries, Covid-19, Racism and Politicization: Media in the Midst of a Pandemic examines how the media in Australia, Bangladesh, China, India, New Zealand, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and the United States have responded to the pandemic, and highlights issues specific to these countries, such as racism, Sinophobia, media bias, stigmatisation of victims and conspiracy theories.

This book explores how the covid-19 coverage developed over the year 2020, with special focus given to the first six months of the year when the reporting trends were established.

The introductory chapter points out that the media deserve scrutiny for their role in the day-to-day coverage that often focused on adversarial issues and not on solutions to help address the biggest global health crisis the world has seen for more than a century.

In chapter 2, co-editor Dr Kalinga Seneviratne, former head of research at the Asian Media Information and Communication Centre (AMIC) takes a comprehensive look at how the blame game developed in the international media with a heavy dose of Sinophobia, and how between March and June 2020 a global propaganda war developed.

He documents how conspiracy theories from both the US and China developed after the virus started spreading in the US and points out some interesting episodes that happened in the US in 2019 that may have vital relevance for the investigation of the origins of the virus.

Attacks on WHO

The attacks on the World Health Organisation (WHO), particularly by the former Trump administration, are well documented with a timeline of how WHO worked on investigating the virus in its early stages with information provided from China.

The chapter also discusses the racism that underpinned the propaganda war, especially from the West, which led to the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s controversial call for an “independent” inquiry into the origins of the pandemic that riled China.

“The covid-19 pandemic has exposed the inadequacies and inequalities of the globalised world. In an information-saturated society, it has also laid bare many political economy issues especially credibility of news, dangers of misinformation, problems of politicisation, lack of media literacy, and misdirected government policy priorities,” argues co-editor Sundeep Muppidi, professor of communications at the University of Hartford in the US.

“This book explores the implications of some of these issues, and the government response, in different societies around the world in the initial periods of the pandemic.”

In chapter 3, Muppidi examines specifically the US media coverage of covid-19 and he explores the “othering” of the blame related to failures and non-performances from politicians, governments and media networks themselves.

Yun Xiao and Radika Mittal, writing about a study they have done on the coverage in The New York Times during the early months of the covid-19 pandemic, argue that unsubstantiated criticism of governance measures, lack of nuance and absence of alternative narratives is indicative of a media ideology that strengthens and embeds the process of “othering”.

Ankuran Dutta and Anupa Goswani from Gauhati University in Assam, India, analyse the coverage of the covid-19 crisis in five Indian newspapers using 10 key words. They argue that the Indian media coverage could be seen as what constitutes “Sinophobia” with some mainstream media even calling it the “Wuhan Virus”.

Historical background

They trace the historical background to India’s anti-China nationalism, and show how it has been reflected in the covid-19 coverage, especially after India became one of the world’s hotspots.

“This Sinophobia hasn’t much impacted on the government policy; rather it has tightened its nationalist sentiments promoting Indian vaccines over the Chinese.” They say the Indian media’s Sinophobia has abated after the delta variant hit India.

“The narrative concerning covid-19 has taken a sharp turn bringing out the loopholes of the government’s inability to sustain its vigilance against the virus,” he notes, adding, ‘considering the global phobia concerning the delta variant put India in a tight spot and India has to defend itself from its newfound identity of being the primary source of this seemingly untameable variant.”

Zhang Xiaoying from the Beijing Foreign Studies University and Martin Albrow from the University of Wales explain what they call the “Moral Foundation of the Cooperative Spirit” in chapter 4.

Drawing on Chinese philosophical traditions—Confucianism, Daoism and Mohism—they argue that the “cooperative spirit” enshrined in these philosophies is reflected in the Chinese media’s coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic in its early stages. Taking examples from the Chinese media—Xinhua, China Daily, Global Times and CGTN—they emphasise that the Chinese media has promoted international cooperation rather than indulge in blame games or politicising the issue.

This chapter provides a good insight into Chinese thinking when it comes to journalism.

Chapters on Sri Lanka and New Zealand examine how positive coverage in the local media of the governments’ initially successful handling of the covid-19 pandemic has contributed to emphatic election victories for the ruling parties.

Hit on NZ media industry

David Robie, founding director of Auckland University of Technology’s Pacific Media Centre, explains in his chapter how New Zealand’s magazine sector was devastated by the pandemic lockdowns and economic downturn, although enterprising buy-outs and start-ups contributed to a recovery.

He points out that a year later, in April 2021, Media Minister Kris Faafoi, himself a former journalist, announced a NZ$50 million plan to help the media industry deal with its huge drop in income, because, as he says, Facebook and Google were instrumental in drawing advertising revenue away from local media players.

The chapter from Bangladesh offers a depressing picture of the social issues that came up as the virus spread, such as the stigmatisation and rejection of returning migrant worker who have for years provided for families back home, and how old people were abandoned by their families when they were suspected of having contacted the virus.

The chapter gives a clear illustration of how the adversarial reporting culture of the media impacts negatively on the community and its social fabrics.

But, the chapter’s author, Shameem Reza, communications lecturer at Dhaka University, says that when the second outbreak started in March 2021, he observed a shift in the media coverage of covid-19 pandemic.

Now, the stories are more about harassment and discrimination, such as migrant workers facing hurdles to access vaccine; uncertainty over confirming air tickets and flights for their return; and facing risk of losing jobs and becoming unemployed. Thus, now the media coverage particularly includes ordinary peoples’ suffering.

Reza believes that the initial stigmatisation of victims, had influenced social media coverage of harassment, and “changed agendas in the public sphere”.

Lack of skills, knowledge

The authors argue in the chapter on the Philippines that the covid-19 coverage exposed the “lack of skills and knowledge in reporting on health issues”. Said a senior newspaper editor, “in the past, whenever there were training opportunities on science or health reporting, we’d send the young reporters to give them the chance to go out of the newsroom. Now we know we should have sent editors and senior reporters.”

In the concluding chapter, Seneviratne and Muppidi discuss various social and economic issues that should be the focus of the coverage as the world recovers from the covid-19 pandemic that reflects the inequalities around the world. These include not only vaccine rollouts, but also the vulnerability of migrant labour and their rights, the plight of casual labour in the so-called “gig economy”, priority for investments on health services, the power of Big Tech and many others.

This book is an attempt to raise the voices of the “Global South” in discussing the media’s role in the coverage of the covid-19 crisis, explain Seneviratne and Muppidi, pointing out that there cannot be a return to the “normal” when that is full of inequalities that have been exposed by the pandemic.

“There are many issues that the media should be mindful of in reporting the inevitable recovery from the covid-19 pandemic in 2021 and beyond.”

Krishan Dutta is a freelance journalist writing for IDN – News (In-Depth News). An earlier version of this review was first published by IDN-News under the title “New book explores how adversarial reporting culture drives politicised covid-19 coverage and this version is republished from Pacific Journalism Review.

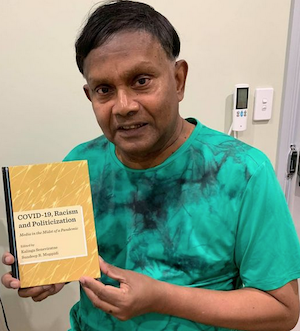

- Covid-19, Racism and Politicization: Media in the Midst of a Pandemic, edited by Kalinga Seneviratne and Sundeep R. Muppidi. Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2021. 230 pages. ISBN: 9781527570894