ANALYSIS: By Richard Shaw, Massey University; Bronwyn Hayward, University of Canterbury; Jack Vowles, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Jennifer Curtin, and Lindsey Te Ata o Tu MacDonald, University of Canterbury

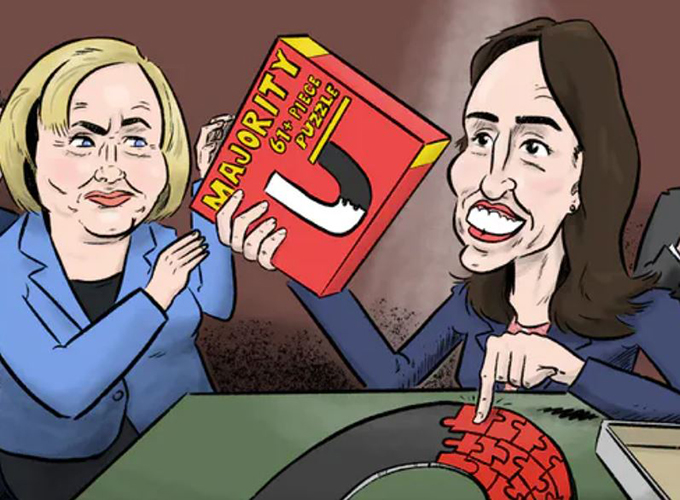

The pre-election polls suggested it might happen. But the fact that Labour and Jacinda Ardern have provisionally won an outright majority and the mandate to govern New Zealand alone is more than an electoral landslide — it is a tectonic shift.

You can see the full results and compare them with the 2017 election here.

This is also not a result the mixed member proportional (MMP) voting system was designed to deliver.

- READ MORE: ‘ We will … govern for every New Zealander’, says Ardern after Labour victory

- Jacinda Ardern promised ‘transformation’

- More NZ election stories

- Preliminary election results

The challenge for Ardern and Labour now will be to translate that mandate — and the fact that their natural coalition partner the Greens have performed strongly too — into the “transformational” agenda promised since 2017.

For now, there is much to digest in the sheer scale of the swing against National and the likely shape of the next Parliament.

The Conversation’s panel of political analysts deliver their initial responses and predictions.

Labour rewarded for its covid response

Dr Jack Vowles, professor of political science, Te Herenga Waka/Victoria University of Wellington:

It’s an historic MMP result, and that is down to one thing: covid-19. Labour and Ardern made the right calls. Comparative analysis of covid responses internationally shows it’s not just a matter of what you do, it’s a matter of whether you do it soon enough.

Labour did that and have been rewarded electorally.

The polls were largely in line with what looks like the final result will be — the Greens have done a bit better, as has Labour, and National appreciably worse. It’s unlikely they can claw that back to where earlier polls had them. Special votes will be roughly 15 percent of the total and they are likely to go more in Labour’s and the Green’s direction, as they did in 2017.

The swing away from National is pretty dramatic. If it is indeed the first single party majority under MMP and it is very unlikely to happen again for a long time. The big question is whether Labour wants to do a deal with the Greens when they don’t have to.

It might be in their interests to do so in the long run — in 2023 Labour probably will not be in such a strong position. If they have a good relationship with the Greens it might stand them in better stead, but it’s a tough strategic call.

As for New Zealand First, according to analysis of the Reid Research polls over the past months, most of their vote has gone to Labour. And that is simply another reflection of this being a covid election.

Labour was rewarded for protecting New Zealanders, particularly the most vulnerable — and that is in the traditions of the Labour Party.

Labour win masks smaller victories

Dr Bronwyn Hayward, professor of politics, University of Canterbury:

With a record 1.9 million people casting an early vote, this was always going to be an election with a difference. Younger voters also enrolled in historic numbers, with a significant increase in those aged 18 to 29 enrolling across the country.

A generation’s hopes and aspirations now hang in the balance.

Labour’s victory offers the party command of the house, an unprecedented situation in an MMP government. But it masks some other remarkable achievements. The Māori Party’s fortunes have risen, with very little national media coverage.

ACT has been transformed from a tiny grouping of 13,075 party votes in 2017 to win an astonishing 185,723 party votes this year.

The Greens defied a dominant mantra that small parties who enter governance arrangements are eclipsed in the next election. They maintained their distinctive brand and should bring ten MPs into the House.

The epic struggle for Auckland Central by Chlöe Swarbrick (Green) and Helen White (Labour) has pushed up both the Green and the Labour vote — a microcosm of the wider shift to a progressive left electorate bloc.

The challenge now is for Labour to decide to open this victory to support parties. What happens next matters as much as the election itself.

Will a Labour government led by the most popular prime minister in New Zealand’s history be incrementalist or transformative in tackling the biggest challenges any government has faced in peacetime?

The Māori Party returns

Dr Lindsey Te Ata o Tau MacDonald, senior lecturer in politics, University of Canterbury:

Last night demonstrated that Māori voters continue to waver between the Māori Party via its electorate MPs and Labour via the party vote.

On one side there is the legacy of Tariana Turia and Pita Sharples, and the founding generation of “by Māori, for Māori, with Māori” in the post-settlement era. Rawiri Waititi, who may well take Tamiti Coffey’s seat in Waiariki, is the living embodiment of the success of that struggle.

The other side is exemplified by Koro Wetere’s triumph in 1975 in creating the Waitangi Tribunal. These two stories — struggle via protest and gradual legislative change — were deeply intertwined in Labour’s grip on the Māori seats until 2003.

Then, in one grand racist gesture, Labour proved itself a colonial government by taking the last Māori land, the foreshore and seabed, by statute.

Māori voters have not forgotten the deep betrayal of that removal of their property rights. Hence the close races tonight for those who truly inherit the mantle of the Māori party’s founders, such as Waititi and Debbie Ngarewa-Packer.

John Tamihere’s close run in Tāmaki Makaurau is more just politics, Auckland style, as usual. He may be wondering why he didn’t go with ACT, which has brought in interesting new Māori talent.

What happened to the ‘shy Tories’?

Dr Jennifer Curtin, professor of politics and policy, University of Auckland:

Two aspects are interesting in this post-MMP history-making election. The first is that Labour has made significant gains in the regions. It is now not solely a party of the cities — it looks to have claimed seats that have long been forgotten as bellwethers (Hamilton East and West), as well as those provincial hubs in Taranaki, Canterbury, Hawkes Bay and Northland.

This suggests that while New Zealand First had been gifted the Provincial Growth Fund to deliver regional economic growth to the regions, it was Labour that reaped the rewards of this largesse.

While covid-19 is definitely part of the reason for Labour’s success, the support is likely to have come from across the political spectrum, bringing its own challenges.

This leads into the second interesting point. Judith Collins reportedly did not share internal polling with her caucus, but public polls suggested National support was in the 30% region. Collins argued the result would be higher, that there were shy Tories who would turn out for National.

In fact, this result suggests it was “shy lefties” the polls had failed to capture. And it appears undecided voters decided National was not for them this time.

With such a mandate, Ardern must deliver

Dr Richard Shaw, professor of politics, Massey University:

The Prime Minister asked for a mandate and she got it. Final numbers won’t be known for a couple of weeks, but the headline result was one last seen in New Zealand in 1993: a political party in possession of a clear parliamentary majority.

All the same, Jacinda Ardern will be chatting with Green Party leaders Marama Davidson and James Shaw (and perhaps the Māori Party, depending on events in Waiariki) about how Labour and the Greens might work together in the 53rd Parliament. Perhaps a formal coalition, but more likely a compact of some sort.

She doesn’t need the Greens to govern and their leverage is limited. But a lot of people who voted for Labour would not have done so under other circumstances (no Ardern, no covid). At some point they will return home to National.

Labour will already be thinking about 2023 and Ardern knows she will need parliamentary friends in the future.

But right now Ardern has a chance to consign the centre-right to the opposition benches for the next couple of electoral cycles. There is a chasm between the combined Labour/Green vote (57 percent) and National/ACT (35 percent).

ACT had a good night but the centre-right had a shocker. National now has a real problem with rejuvenation. With a low party vote, and having lost so many electorates, their ranks will look old and threadbare in 2023.

This election is tectonic. Ardern has led Labour to its biggest victory since Norman Kirk, and enters the Labour pantheon with Savage, Lange and Clarke.

Once special votes are counted, Labour could be the first party since 1951 to win a clear majority of the popular vote.

It has won in the towns and in the country. It won the party vote in virtually every single electorate. Labour candidates, many of them women (look for a large influx of new women MPs), have won seats long held by National.

Last night Labour was looking like the natural party of government in Aotearoa New Zealand. Ardern has her mandate — now she needs to deliver.![]()

Dr Richard Shaw, professor of politics, Massey University; Dr Bronwyn Hayward, professor of politics, University of Canterbury; Dr Jack Vowles, professor of political science, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Dr Jennifer Curtin, professor of politics and policy, and Dr Lindsey Te Ata o Tu MacDonald, senior lecturer in politics, University of Canterbury. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.