ANALYSIS: By Sally Young of the University of Melbourne

Many newspapers betrayed their readers during the Great Depression and now some are doing so again during the coronavirus pandemic.

During the Depression, Australia’s major daily newspapers loudly resisted calls for economic stimulus to revive the economy. Even the tabloids – whose working class audiences were feeling the full brunt of unemployment – campaigned instead for government spending cuts that hit their readers hard.

Self-interest was behind this. The companies and individuals behind Australia’s most popular daily newspapers in the early 1930s were bondholders who had lent enormous sums of money to Australian governments before the Depression.

READ MORE: A matter of trust: coronavirus shows again why we value expertise when it comes to our health

So had banks, trustee and life insurance companies that were allied with newspaper owners, and also major newspaper advertisers.

If Australian governments had not made severe cuts to spending and instead injected money into the economy through welfare and job creation projects, they would not have been able to pay back their debts. Domestic bondholders would have lost millions in interest payments.

Now, we see some news outlets again betraying their readers by prioritising business over public health.

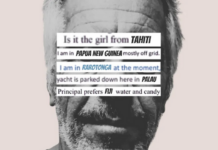

In the Murdoch News Corp/Fox Corporation stable in the US, Fox News downplayed the spread of the virus for as long as it could.

Its presenters ridiculed predictions about its impact as coming from “panic pushers” and liberals out to damage Trump, while the Wall Street Journal editorialised that shutdowns might be safeguarding public health but “at the cost of its economic health”.

Trump jumped on cue and began spouting the same shameful rhetoric that the cure might be worse than the disease because of its economic impact. He wanted Americans back to work by Easter.

Murdoch’s Sun in the UK represented shutdowns there with a bleak front page calling them “HOUSE ARREST” and showing a padlock over the Union Jack.

In the Murdoch outlets in Australia, these views are being faithfully reproduced by Andrew Bolt of the Herald Sun and Sky News. Bolt’s column on March 30 was headed “Aussies should be back at work in two weeks”.

During the Great Depression, the mainstream press strongly reflected the economic conservatism of bankers, economists and business leaders. The most vehement outlets were the Argus and the Herald in Melbourne, The Sydney Morning Herald and the Daily Telegraph in Sydney, the Mercury in Hobart, and the Brisbane Telegraph and Brisbane Courier. They attacked the Scullin Labor government’s plan to reflate the economy through government stimulus as “economic insanity”, “a dangerous experiment”, “grotesque and menacing”.

But in a turn of phrase that even those papers might have found too hysterical, Bolt recently described economic stimulus packages during coronavirus as “Marxism”. This is despite the fact that economic stimulus is now so widely accepted as part of a mainstream economic toolkit that conservative politicians are using it in Australia, the UK and the US.

Sky News host Alan Jones has also downplayed the virus, saying “we are living in the age of hysteria” and that he wants to see the emphasis placed on protecting people “in nursing homes and hospitals instead of schools and football stadiums”.

Sky News video: ‘We are living in the age of hysteria.’

Right-wing commentators – presumably working from home themselves – are keen to get everyone back to work in the midst of a pandemic, even though the medical advice says otherwise.

The usual pretence that they are on the side of their audience falls away at a time of crisis. They are representing the interests of business – particularly their own.

Media companies that were already financially fragile are extremely worried about coronavirus. The sudden halt to business has meant the loss of advertising revenue, possibly for a long period, but also the loss of reader income. This means people have less to spend on media and on buying advertisers’ products.

Combined with this is the dramatic loss of sport (of vital importance to the struggling Foxtel, Kayo Sports and tabloid newspapers) and also the end of house auctions when real estate sections and real estate websites were one of the few remaining bright spots for the newspaper groups. The bread-and-butter events that newspapers cover, from entertainment and leisure to restaurant and movies, have stopped, and nobody knows for how long.

These are unprecedented and menacing threats to commercial media groups. At News Corp, there is the added pressure of a transition in leadership from the 89-year-old Rupert Murdoch to his son, Lachlan Murdoch, a less tested – and less trusted – leader who is unlikely to have the business nous of his father or even his grandfather, Keith Murdoch.

As a journalist and editor, Keith Murdoch was one of those who promoted business interests during the Depression. Rupert’s father was also a vehement conscriptionist during the first and second world wars. Although Keith never signed up for military service himself, he propagandised, almost obsessively, for conscription and called on other men to make a sacrifice for a greater cause.

We need to beware the media commentators of today, anti-science and anti-expertise armchair generals, who likewise call on their fellow citizens to do things they won’t do themselves.

By Sally Young, professor of the University of Melbourne. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.