The trailer for Will Watson’s documentary on Bougainville peacemaking, Soldiers Without Guns.

FILM REVIEW: By David Robie

While a gripping film about the apocalyptic Bougainville war, or more accurately the peace that ended the decade-long conflict, opened in cinemas across New Zealand last week, an island roadshow has been taking place back in the Pacific.

Initiated by the United Nations, the roadshow – featuring Bougainville President Father John Momis, many of his cabinet members and UN Resident Coordinator Gianluca Rampolla – is designed to help prepare the Bougainvillean voters to decide on their future.

This future is due to be put to the test in a referendum on October 17 in the crucial political outcome of an extraordinary peace process that began in chilly mid-winter talks at Burnham Military Camp near Christchurch in July 1997.

The vote is already four months delayed, partly due to spoiling tactics of Peter O’Neill’s Papua New Guinean government which would avoid the vote if it could.

In any case, the vote is not binding and the O’Neill government may not even honour it, even if there is an overwhelming vote for independence in the island with a population of 250,000.

The choice is simple: Voters will be asked to choose between greater autonomy and full independence. The vote is expected to favour independence.

Also at stake is the future of the Panguna – once the mainstay of Papua New Guinea’s economy and now abandoned because of the environmental devastation caused by the huge Australian-owned copper mine – and the right of a people to choose their own destiny free from rapacious foreign extraction industries.

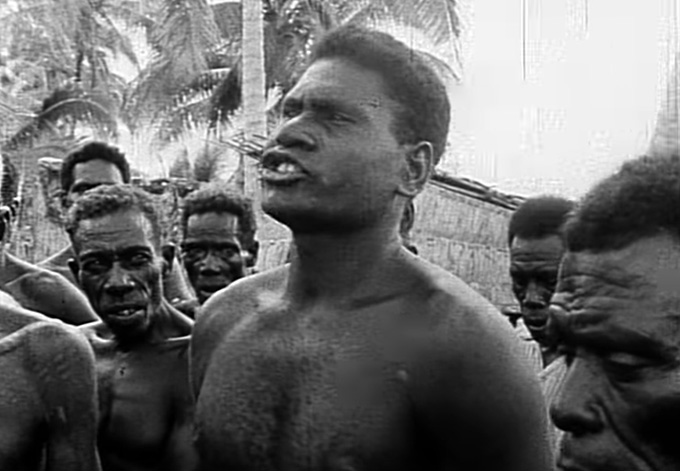

After almost 10 years of civil war when an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people lost their lives through the actual fighting between the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) and other armed groups and the Papua New Guinean military, and through deaths from lack of medical treatment and starvation as a result of a military blockade around the island state, a breakthrough was achieved in New Zealand.

Exhausted by the deadlock, the deprivations of the war and 14 failed attempts at negotiating a peace, talks in the bitter cold at Burnham sparked off the long journey for a lasting peace. As former North Solomons provincial government official and a peace process officer Robert Tapi recalls:

The silent majority of Bougainvilleans were tired of war and longed to return to normal village life. Women’s groups, church groups and chiefs increased the pressure on both the BRA and the PNG-backed Bougainville Transitional Government to negotiate for peace.

On all sides, the likely cost of victory was proving too high. The moderate revolutionary leaders realised that even if they did “win”, they “would inherit a hopelessly divided society”.

The first meeting resulted in the Burnham Declaration of July 18, 1997, which urged the leaders to call a ceasefire and for the establishment of an international peacekeeping force with the withdrawal of the PNG Defence Force.

Following the Burnham Truce and the endorsement of a Truce Monitoring Group (TMG) in Cairns in November 1997, a further Burnham meeting in January 1998 produced the Lincoln Agreement and paved the way for the Ceasefire Agreement in Arawa on April 30, 1998.

The success of the breakthrough in Burnham and the following meetings was thanks to the inclusion of women’s groups, churches and local chiefs as well as the political opponents, meeting on neutral territory and with New Zealand not intervening in the talks. Also helpful was then Foreign Minister Don McKinnon’s friendly and chatty style with the delegates, which boosted Bougainvillean morale.

Filmmaker Will Watson stepped up to tell the extraordinary New Zealand peacekeeping story initially through an award-winning 2018 documentary for Māori Television, Hakas And Guitars, following up with this year’s feature film Soldiers Without Guns.

He had been monitoring the war and aftermath while a journalism student and began to put together a project team in 2005. Ironically, due to funding and other obstacles, it took him 13 years to complete the feature film – longer than the actual war.

A couple of years later, in 2007, he had a film crew on the ground in Bougainville to carry out interviews and gain invaluable footage. His documentary is an inspiring and fitting tribute to the innovative “guitars, waiata and wahine” approach of the NZ-led peacekeeping force.

By concentrating on a strategy of winning the hearts and minds through hundreds of kilometres of foot slogging treks to villages and communicating directly and honestly with ordinary people, the soldiers gained the trust of Bougainvilleans from all sides.

It was a courageous and insightful decision by the first mission commander, Brigadier Roger Mortlock, now retired, to go to Bougainville without weapons and guarantee the peace. He had experienced a UN peacekeeping failure in Angola and was determined this mission would succeed.

Another key factor in the success was Major Fiona Cassidy, an Army public relations manager at the time, and her ability to communicate in a meaningful way with the Bougainvillean women in what is a matriarchal society.

In a recent RNZ Pacific interview, she admitted finding the challenge a bit “scary”:

“When you looked at the country brief, you knew that you were not going into a benign environment. It actually was hostile. So it was a little bit scary thinking, ‘Okay, we’re going to a country which has been at war for so long, it still isn’t stable, and we’re going in unarmed.'”

During the start of the Bougainville war, I was head of the journalism programme at the University of Papua New Guinea and reported the first year of the conflict in a cover story for Pacific Islands Monthly. As part of this, I revealed how a New Zealand environmental consultancy unwittingly became a catalyst for fuelling the conflict.

I wrote in my 2014 book Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face: Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific:

Apart from convoys with soldiers riding shotgun and yellow ochre Bougainville Copper Limited trucks packed with security forces sporting M16s, you would hardly guess that a guerrilla war was in progress near the Bougainville provincial capital of Arawa. But once you reached the sandbagged machinegun nest in Birempa village at the foot of the rugged mountain jungles of the Crown Prince Range, the tension started to rise.

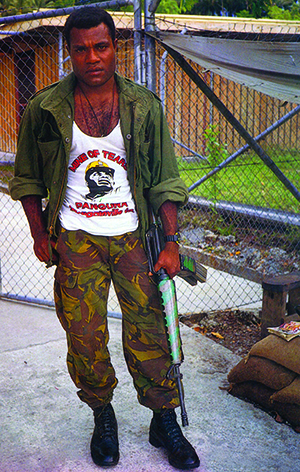

Scanning the dense vegetation for a sign of the militants of the Bougainville Republican Army (BRA)—known as Rambos in the first year of the decade-long civil war – the Papua New Guinea Defence Force soldier manning the machinegun didn’t notice the irony of the T-shirt he was wearing.

Scrawled across his chest were the words MINE OF TEARS, a word play on the title of Richard West’s 1972 book River of Tears: The rise of Rio Tinto-Zinc Mining Corporation. The book was an expose of the mining operations by BCL’s parent company CRA Limited of Australia—a subsidiary of Britain’s Conzinc-Riotinto—and it had already become the “Bible” of the many of the militants.

At the time I was reporting on the fledgling war for a cover story featured by Pacific Islands Monthly in its November 1989 edition entitled MINE OF TEARS: BOUGAINVILLE ONE YEAR LATER. No other journalists were on the ground at the time, and the only other people staying at the small hotel in the port town of Kieta were soldiers, some cradling guns on their knees when having dinner. The atmosphere was surreal and ghostly in those early days.

The problems of Bougainville cannot be divorced from the rest of the country, or even from the rest of the Pacific. At stake are the crucial issues of a conflict between Western concepts of land ownership and indigenous land values, the equity between the national government, provincial administration and the traditional landowners, and a choice between genuine sovereignty over resource development projects or dependence on foreign control.

For those of us who have had some involvement in the Bougainville war bearing witness, Will Watson and his crew deserve huge praise for bringing this story to the big screen, and honouring New Zealand’s contribution to peace – Australia couldn’t have done it – and providing hope for Bougainville’s future.

With luck, the island will become independent and bring some meaning to all that terrible loss of life and deprivation.

- Soldiers Without Guns, documentary, 92min. Director Will Watson. Narrated by Lucy Lawless.

Professor David Robie is director of the Pacific Media Centre. This review is republished from Pacific Journalism Review with permission.

“Australia Couldn’t have done it.” – certainly not in that way. As someone who served there in the initial Truce Monitoring Group, I was deeply impressed by New Zealand’s leadership. That said, I also recall the enormous value of service personnel from Vanuatu and other much smaller nations. Phil Smith SQNLDR retd. RAAF

Comments are closed.