IN-DEPTH: By Dr Lee Duffield, recently in Kanaky/New Caledonia

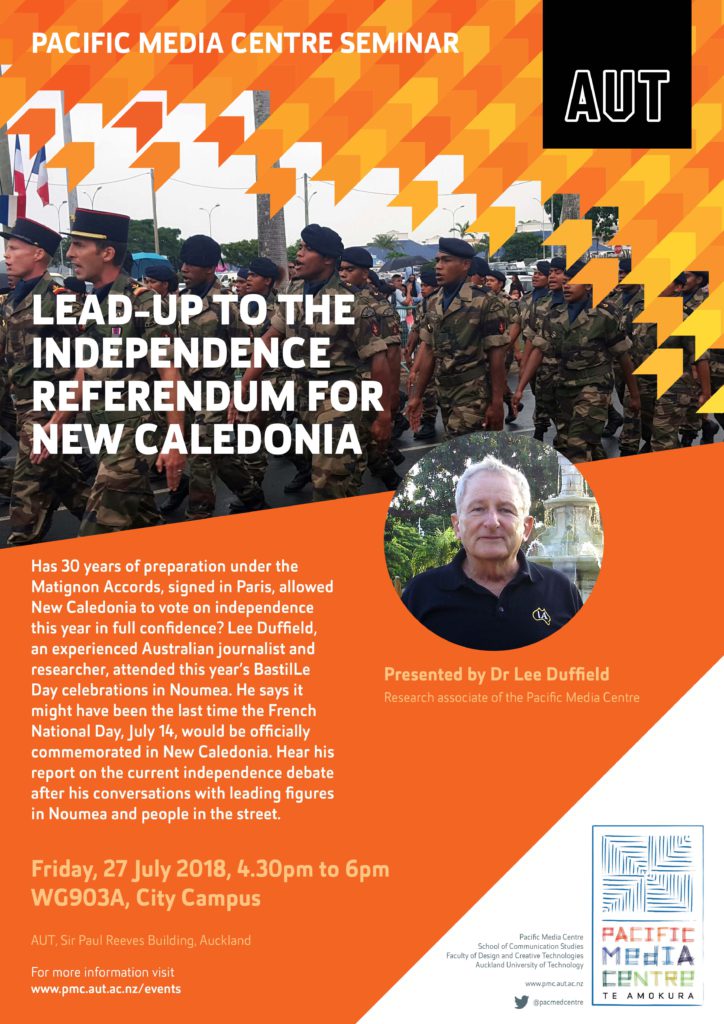

The Quatorze Juillet (14 July) events in Noumea this month, as in any small French city, reflected the grand military parade down the Champs Elysees in Paris – ranks of soldiers and a senior officer taking the salute.

It was like a refrain from colonial times, kepis under the coconut palms, as if no breath of a wind of change was anywhere being felt.

The impression of total normality was strong also the evening before at the informal public celebrations concentrated on Noumea’s town square, the Place des Cocotiers.

READ MORE: Part 1 of a series of three articles on Kanaky/New Caledonia

This was patriotic enough, red-white-and-blue everywhere, (even with a can-can, and a visiting Army band from Australia), anticipating the joy of France’s victory in the World Cup football a few nights later. Mostly a big fete being enjoyed by a highly multicultural community.

Signs of the future

A taste of the inter-communal character of New Caledonia was given at the tail-end of the day’s parade, by a local cadet platoon slow-marching to a Melanesian chant.

It was not in the tradition of the Grande Armee of Napolean; it was imaginably the young officer corps of an independent country.

Not that a full independence is greatly expected from the coming vote, mandated under agreements made by the country’s political groups with the French government – the Matignon Accord (1988) and Noumea Accord (1998).

Opinion polls have been running strongly against it and even many in the indigenous Kanak community can be heard to say it is “not yet the time”.

Voices from other times

Certainly the weekend events of Bastille Day and then the World Cup made it “France Week”, not the best time to talk change.

“People realise the independence idea is not practical”, said “Jacques”, a fifth-generation member of the European settler society, the Caldoches.

A well-established and prominent business owner, he was uneasy about speaking under his own name on the divisive issue of the referendum – exposure would create difficulties of one kind or another.

But he was prepared to recite the standard analysis of the anti-indépendentiste cause, beginning with the observation that French investment and a high standard of living had won a lot of hearts.

“Even in the Loyalty Islands province, which is a big Kanak area, the opinion polls which always showed a strong ‘yes’ vote for independence – as much as 70 percent, are now showing 50/50 or even a slight ‘no’,” he says.

“Things have been slowly improving with the circumstances of life for most people, and I would agree some change and reform is a good thing, but slowly — it needs to be long-term.

“Women are helping. In the tribus, the villages, they do so much of the work providing for the household and raising children, and they are the practical ones.”

Keeping watch on the future

Jacques admits to being worried about what the future may hold, “only a little worried” over the idea of violence or revolt affecting his family.

He does take some comfort being able to tell of a precautionary doubling of the paramilitary Gendarmerie and National Police forces, reinforced from France with the approach of referendum day on November 4 – together with the availability of an extra intervention force in Tahiti.

Yet his most serious concern is about what can be agreed on next among the different parties.

“We don’t know what will take place after November 4, or what it will be like here in another 10 or 20 years.

“We definitely need a road map, and we should manage all this together.”

That is a common position of the Caldoche and the general settler community, which began falling back on prepared positions after the violent confrontations of the 1980s that brought new Caledonia close to civil war.

Even the most strongly “French loyalist” anti-indépendentiste parties, barring a few on the margins, want just the status quo – no fast forward but no winding back the clock.

They have committed to abiding by decisions of the referendum and have not talked of any attempts at stamping out the independence movement.

Gone are the days when the local European gentry had the ear of French ministers who were themselves brought up in the colonial era, and could hold off change.

New order

Instead the territory has been through 30 years of managed change, including ingenious and effective reforms, all falling short of a full independence, but all focused on the referendum process now about to start.

The changes:

- Power sharing in an elected territory parliament and executive Council, with both indépendentiste and anti-indépendentiste members.

- The formation of a consultative Senate for customary or traditional Kanak leadership (not unlike the body envisaged by Indigenous Australians in their Uluru proposals – struck down unexpectedly this year by Prime Ministerial decree). It gives additional representation to people from the Tribus, tribes or clans, who have a special customary legal status as well as their full French citizenship, and are subject to customary laws.

- Major funding of the government from France.

- A safety valve provision that says, independence will follow a “yes” vote, but after a “no” indépendentistes in the parliament can still get it reconvened, to have a second, or even third referendum.

- Three provinces with extensive powers and sustainable budgets set up after 1988, one of which (South province on the main island, Grande Terre) is predominantly “French”, the other two (North province and the Loyalty Islands) are Kanak territory and mostly run by local Kanak politicians.

Experience in government, money and Big Nickel

It all amounts to actual experience in governing a modern democratic state, more than just practising, with the idea that over the three decades the whole society would be “ready” for the decision to be taken at the referendum.

Money is important in setting up the lines of argument and conditioning people’s views about what they hope to obtain in their future.

Three big nickel mines with refining plants and modern ports produce more than 10 percent of the territory’s wealth but crucially well over 80 percent of its export earnings. All arguments come back to the importance of the industry to the economy and ways to get good returns that will benefit the local population.

The point is made everywhere on the anti-indépendentiste side and among neutral observers that actual independence would prompt likely reductions in French government support, over time, and a fall in investor confidence in France or countries like Australia.

Investment from China would almost certainly fill the gap – there is much worry about Chinese interest and ambitions in the Pacific region. Would a newly independent government, strapped for cash to provide benefits to its people, use its powers over immigration and economic policy to admit more participation from China?

What is the direct French financial commitment at this time?

Future security

France has already handed over all powers to the autonomous government in New Caledonia, except for military and foreign policy, immigration, police and currency – and the specific issue in this year’s referendum is whether those will be passed on as well.

The bulk of French national spending on the territory is to pay the soldiers, police and public servants including teachers – bringing up again the sound of marching boots on July 14.

Also various grants come to the local treasury through Paris, like $80 million over 4-5 years for economic development and professional development of personnel, from the European Union.

France is partnered with Australia and New Zealand in guaranteeing security in the South Pacific region. These have a protective role for the 278,000 French citizens in New Caledonia, but the regional connections are strong, so their decision-making this year is being watched closely far and wide.

Dr Lee Duffield is an independent Australian journalist and media academic. He is also a research associate of the Pacific Media Centre and on the Pacific Journalism Review editorial board. This article was first published by EU Australia, and the next two articles will be published by Asia Pacific Report over the weekend.