ANALYSIS: By Selwyn Manning

There is an overlooked aspect of the New Zealand Defence Force’s account of Operation Burnham that when scrutinised suggests a possible breach of international humanitarian law and laws relating to war and armed conflict occurred on 22 August 2010 in the Tirgiran Valley, Baghlan province, Afghanistan.

For the purpose of this analysis, we examine the statements and claims of the Chief of New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF), Lieutenant-General Tim Keating, made before journalists during his press conference on Monday, 27 March 2017. We also understand, that the claims put by the general form the basis of a briefing by NZDF’s top ranking officer to the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Bill English.

It appears the official account , if true, underscores a probable breach of legal obligations – not necessarily placing culpability solely on the New Zealand Special Air Service (NZSAS) commandos on the ground, but rather on the officers who commanded their actions, ordered their movements, their tasks and priorities prior to, during, and after Operation Burnham.

READ MORE: No inquiry – ‘It is the next step in the seven-year cover-up’

*******

According to the New Zealand Defence Force’s official statement, Operation Burnham “aimed to detain Taliban insurgent leaders who were threatening the security and stability of Bamyan Province and to disrupt their operational network”. (ref. NZDF rebuttal)

We are to understand Operation Burnham’s objective was to identify, capture, or kill (should this be justified under NZDF rules of engagement), those insurgents who were named on a Joint Prioritized Effects List (JPEL) that NZDF intelligence suggested were responsible for the death of NZDF soldier Lieutenant Tim O’Donnell.

When delivering NZDF’s official account of Operation Burnham before media, Lieutenant General Tim Keating said:

“After the attack on the New Zealand Provincial Reconstruction Team (NZPRT), which killed Lieutenant Tim O’Donnell, the NZPRT operating in Bamyan Province did everything it could to reduce the target profile of our people operating up the Shakera Valley and into the north-east of Bamyan Province.

“We adjusted our routine, reduced movements to an absolute minimum, maximised night driving, and minimised time on site in threat areas.

“The one thing the PRT [NZPRT] couldn’t do was to have an effect on the individuals that attacked Lieutenant O’Donnell’s patrol. For the first time, the insurgents had a major success — and they were well positioned to do so again.”

For the purpose of a counter-strike, intelligence was sought and Lieutenant-General Keating said: “We knew in a matter of days from local and International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) intelligence who had attacked our patrol [where and when Lt. O’Donnell was killed].”

The intelligence specified the villages where the alleged insurgents were suspected of coming from and Leutenant-General Keating said: “This group had previously attacked Afghan Security Forces and elements of the German and Hungarian PRTs.”

The New Zealand government authorised permission for the Kabul-based NZSAS troops to be used in Operation Burnham.

“What followed was 14 days of reliable and corroborated intelligence collection that provided confirmation and justification for subsequent actions. Based on the intelligence, deliberate and detailed planning was conducted,” Lieutenant-General Keating said.

Revenge, Keating said, was never a motivation. Rather, according to him, the concern was for the security of New Zealand’s reconstruction and security efforts in Bamyan province.

As stated above, Operation Burnham’s primary objective was to identify, capture or kill Taliban insurgent leaders named in the intelligence data.

We know, from the New Zealand Defence Force’s own account, Operation Burnham failed to achieve that goal.

Analysis of the NZDF official account

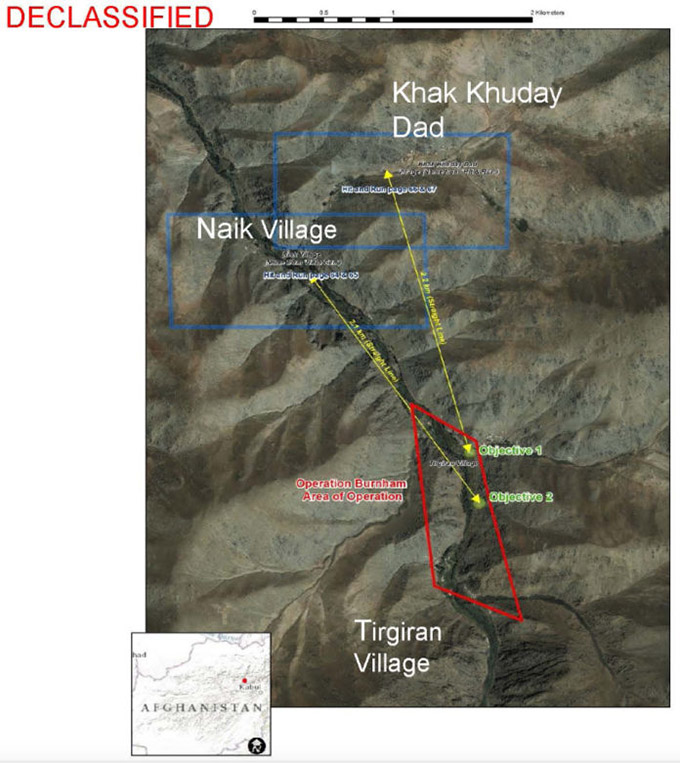

The official account of events that occurred in the early hours of 22 August 2010, describe how Taliban insurgents, realising coalition forces were preparing to raid the area (marked as “Operation Burnham Area of Operation” in a map (slide 3) declasified and released to media on 27 March 2017), formed a tactical maneuver using civilians (women, children and elderly) as a human shield.

Despite the official account placing this group within a building, within a small hamlet, within the area of operation, within Tirgiran Valley, there is no clear definitive official account yet given of what happened to either the civilians or the insurgents.

This appears to be an obvious void in the official record, but one that has failed so far to be scrutinised.

To follow the logic of Lieutenant-General Tim Keating’s account (detailed below), is to discover our defence personnel, who were in charge of the ground and air operation during Operation Burnham, failed to identify what had become of those civilians (women, children, and the elderly), and also importantly the suspected insurgents who Lt. General Keating said during his briefing used the villagers as a human shield.

We know from the Chief of Defence Force’s notes as provided on 27 March 2017, that as Operation Burnham began, NZDF was in command of United States manned aircraft (including helicopters and possibly a AC-130). The aircraft were swarming above the Tirgiran Valley.

From the NZDF account, an NZDF joint terminal air controller was in charge of the air attack against those NZDF had defined as insurgents.

Lieutenant-General Keating stated the alleged insurgents were armed and a NZDF commander authorised the US manned aircraft to commence firing. Weapons-fire then began to rain down on the valley from above.

Meanwhile, NZSAS ground force soldiers prepared to secure their positions and to defend themselves against any potential enemy counter-attack.

Lieutenant-General Keating stated the insurgents responded: “The insurgents, the guerrilla force, the tactic is mixed in with the civilian population, if you like, the term used is a human shield. So they use civilians as a shield.”

He added: “What occurred, is a helicopter was engaging a group of insurgents outside the village, on the outskirts of the village. During that engagement, it was noted by the ground forces there – the SAS ground forces – that some of the rounds [from the US manned aircraft] were falling short, and went into a building where it was believed there were civilians as well as armed insurgents.”

To be clear, from this account, Lieutenant-General Keating stated a group of insurgents were being tracked, targeted, and fired upon by the US manned aircraft and under the command of a New Zealand Defence Force terminal air controller.

Meanwhile, according to the NZDF record, one of the airborne helicopter’s weapon’s sights were not calibrated correctly, and, according to Lieutenant-General Keating, 30mm projectiles went into a building where it was believed there were civilians as well as armed insurgents – remember these 30mm projectiles are capable of penetrating the side of a tank.

For accuracy, Lieutenant-General Keating restated his account: “It is noted, the building, there were armed insurgents in there, but it is believed that there may have been civilians in the building.”

He then added: “There’s no confirmation that any casualties occurred, but there may have been.”

He restated again: “There were civilians in that building.”

Now, this is where the Chief of Defence Force’s account fails to further explain what occurred after that point.

To summarise, the official position of the New Zealand Defence Force is:

- There were civilians in a building within the village that was fired upon by an armor piercing aircraft weapon

- That it was believed insurgents were also in that building

- That civilian casualties or deaths “may have been” or occurred inside the building.

At this juncture, we must consider whether the New Zealand Defence Force ground commanders had a responsibility to determine whether there were Taliban insurgents in the building? And if so, whether they were the individuals listed on the JPEL list, those deemed responsible for the death of Lieutenant Tim O’Donnell? And what of the ground commanders’ legal requirements, the duty of care with respect to civilians, were NZDF commanders on the ground or back in Kabul compelled by law to confirm the status of the civilians, whether they were injured or killed?

When asked by a journalist at the 27 March 2017 press conference: “If there may have been civilian casualties, why not have an inquiry to find out?”

Lieutenant-General Keating replied: “Even if there was, as far as the New Zealand Defence Force has heard, the coalition investigation has, um, said that uh, if there were casualties, the fault of those casualties was a mechanical failure of a piece of equipment.”

This reply does not appear to consider the legal requirements under:

- Second Protocol to the Geneva Convention Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, Article 7: the obligation to provide medical assistance to all wounded, whether or not they have taken part in the armed conflict

- Second Protocol to the Geneva Convention Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, Article 8: the obligation to search for and collect the wounded and to ensure their adequate care

- Second Protocol to the Geneva Convention Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, Article 13: the obligation to protect the civilian population against dangers arising from military operations

- Armed Forces Discipline Act 1971, section 102. This section provides that the commanding officer of a person alleged to have committed an offence under that Act must initiate proceedings in the form of a charge or refer the allegation to civil authorities, unless the commanding officer considers the allegation is not well-founded. While little legal guidance is provided, it cannot be accepted that preliminary inquiries to determine whether an allegation is well-founded can be considered adequate where they fail to obtain evidence from the injured parties, determine their identities or even verify that they exist

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Article 28

- The NZDF Manual of Armed Forces Law provides that there are three types of inquiry in the NZDF: a preliminary inquiry, a court of inquiry and a command investigation. (It appears however the ISAF investigation cited by the Chief of Defence Force was not any of the above forms of inquiry).

Specifically, if you analyse Lieutenant-General Keating’s account, the New Zealand Defence Force commanders failed to identify whether any insurgents were inside the building and whether there were dead or wounded civilians.

Why was this the case? It seems reasonable to suggest, this is an abandonment of logic. It does not make sense.

We know from official NZDF documents the soldiers arrived at the scene of Operation Burnham at 0030 hours on 22 August 2010 and left at 0345 hours, that’s the official record.

To clarify, the NZSAS commandos were in the area of operation for 3 hours 15 minutes. Lieutenant-General Keating stated, near the conclusion of the raid: “The ground force commander chose at that time that there was no longer a threat and they were leaving.”

How could that rationally be the case unless the suspected insurgents inside that building had been checked? Was it not suspected that there were insurgents in that building?

Surely the ground force commanders would be compelled to seek and identify the inhabitants of that building to see if they matched the names/descriptions on the JPEL list? After all, the manhunt for Taliban leadership was the purpose of the raid that night.

Also, logic would suggest, the people inside the building were in part civilians including women and probably children – by Lieutenant-General Keating’s account the group likely included wounded civilians and probably a dead child.

Also, it is reasonable to suggest, considering the events over those 3 hours 15 minutes, the survivors would have been crying, weeping, even howling, and the wounded would likely have been in agony.

It defies belief that the ground force commanders, and their counterparts back in Kabul, were not aware of this building, that the NZDF account states was housing suspected Taliban, and included a group of civilian victims that had been used as a human shield.

The entire area of operation specific to Operation Burnham is a skewed rectangle approximately 500 metres wide by 1 kilometre long, with an intensified operation plan focusing on two small hamlets, each approximately 50×200 metres in area [based on the scale measures of the NZDF map] – named Objective 1 and Objective 2 in the NZDF released material.

To state it simply, the official silence surrounding the above-mentioned building, and the fate of the people inside, speaks volumes. It leaves one to consider at worst whether a crime was committed by New Zealand Defence Force commanders that night – whether by failing in their duty to care for the injured they were in breach of Articles 8, 9 and 13 of the Second Protocol to the Geneva Conventions.

Additional note:

- The Statute of the International Criminal Court defines war crimes as, inter alia, “serious violations of the laws and customs applicable in international armed conflict” and “serious violations of the laws and customs applicable in an armed conflict not of an international character”. (Ref. IHL Definition of war crimes, page 1 (pdf) – ICC Statute, Article 8 (cited in Vol. II, Ch. 44, § 3))

- “The Statute defines as within the scope of the law, the “launching an attack without attempting to aim properly at a military target or in such a manner as to hit civilians without any thought or care as to the likely extent of death or injury amounts to an indiscriminate attack”.

- War crimes can consist of acts or omissions. Examples of the latter include failure to provide a fair trial and failure to provide food or necessary medical care to persons in the power of the adversary.’

At best, if NZDF’s official account is to be relied upon, we are to believe the NZSAS ground commanders failed to ensure the Taliban insurgents they sought were not holed up in a building that had sustained damage from coalition force aircraft. If this assumption is incorrect, at what point had the suspected insurgents left the building? And what had become of the civilians that had been allegedly used as a human shield? Again, the vacuum of information specific to this aspect of the official account needs to be explained, including an explanation as to why NZDF’s account remains vague after six years since Operation Burnham was conducted.

It appears reasonable to assert that this single issue, notwithstanding the irregularities of official NZDF stated “facts”, warrants further official and independent investigation.

As it is, at this juncture, we are left to consider a series of unanswered questions that to date the New Zealand Chief of Defence Force has failed to satisfy. Here are some of them.

Key unanswered questions:

- What were the specific definitions of an insurgent that were used by NZDF for the purposes of evaluation during Operation Burnham and for the purpose of post-operation official analysis? For example; was it deemed that anyone who was male and of a fighting age was defined to be an insurgent?

- Were NZDF soldiers fired upon by individuals (villagers or insurgents) located within the confines of the villages or surrounding area during Operation Burnham?

- Was the individual who was killed by a NZSAS soldier or NZDF personnel carrying a weapon at the time of this shooting? If so, had he fired or attempted to fire his weapon in an attempt to kill or wound NZDF personnel?

- How long in minutes were the coalition forces’ helicopters, and any other airborne craft, firing their weapons on the villages and surrounding region during Operation Burnham?

How long in minutes were NZSAS soldiers involved in securing the operational area from real or potential insurgent attack? - Did NZDF personnel at anytime seek to identify individuals (and their status, injured, killed, or otherwise) who were located inside or near the building that Lt. General Keating said had suffered damage from an alleged mis-aimed firing from an airborne coalition aircraft?

- Were those who were injured or killed within sight of NZDF personnel before, during, and/or after the alleged mis-aimed firing?

- How many individuals did the NZDF personnel suspect were inside the building?

- How many of these people did the NZDF personnel suspect were civilians?

- How many were suspected of being women?

- How many were suspected of being children?

- Lieutenant-General Keating suggested that one of the individuals that may have been killed during Operation Burnham was a six year-old child. What was the gender of this child?

- Was their any attempt to identify this six year-old victim?

- Was this child Fatima, the three year-old child identified in the Hit & Run [ISBN 978 0 947503 39 0] book? If not, then who was this child?

- What actions did NZDF personnel do to exercise their duty of care obligations to the injured and to civilians?

- What reports, cautions, evaluations were written and/or submitted regarding Operation Burnham to NZDF by the NZDF legal officer who was on the ground during Operation Burnham?

The twisting turning official account – is this smoke and mirrors?

As a consequence of the Hit & Run book [ISBN 978 0 947503 39 0] being published, New Zealand Defence Force’s top ranking soldier, Lieutenant-General Tim Keating admitted civilians “may have been” killed during the operation.

Up until 27 March 2017, for the past six years, New Zealand Defence Force has insisted that no civilians were killed during Operation Burnham on 22 August 2010.

But on Monday, under questioning from the media, at the March 27 press conference, Lietenant-General Keating stated that the NZDF’s new “official line” regarding civilian deaths was “there may have been”.

He then attempted to suggest that NZDF’s previously stated position – that claims of civilian deaths were “unfounded” – was basically the same thing.

“I’m not going to get cute here and say it’s a twist on words, it’s the same thing, ‘unfounded’, ‘there may have been’. The official line is that there may have been casualties,” Lieutenant-General Keating said.

A journalist then challenged him further suggesting: “They’re different things, one means they didn’t happen and one mean might’ve done.”

Lieutenant-General Keating then replied: “You’re right…the, the, the official line is that civilian casualties may have occurred, but not corroborated.”

When asked how many insurgents were killed, Lieutenant-General Keating replied: “A significant number of insurgents, identified insurgents, were killed during Operation Burnham.”

When asked again how many were killed, Lt. General Keating stated: “Nine.”

When asked if NZDF had the names of the insurgents that were killed, he replied: “No, we do not have names of insurgents.”

This trajectory, inching toward a truth, occurred under tight questioning by a journalist, over just a few minutes.

What further truths will become relevant to understanding what occurred that night in Khak Khuday Dad and Naik villages should a commission of inquiry be established?

The inconsistencies – a summary

In evaluation, it is reasonable to assert the official government inconsistencies observed along a six-year timeline offer the appearance of a military hierarchy that has being dragged, by degrees, (mainly by the work of Jon Stephenson, an investigative journalist specialising in war and conflict reportage) into an arena where the floodlight of public interest ought to shed light on secrets long since filed into a dark place.

However, considering the above, rather than responding openly to the challenge of meeting its responsibilities to the New Zealand Minister of Defence and public, the New Zealand Defence Force appears resistant to its obligations toward open and accurate disclosure of non-classified fact.

In conclusion, if this is true, this conduct exhibited by the officials of New Zealand Defence Force and its Chief Lieutenant-General Tim Keating is hardly a defining benchmark of “exemplary” standards.

Actually, the admissions of relevant information, that is forthcoming only when lanced from the New Zealand Defence Force under questioning, offers the impression of a smoke and mirrors operation – it may appear churlish to suggest, but perhaps the post-Operation Burnham aftermath ought to be referred to as Operation Desert Road (bleak, cold, inhospitable, proceed with caution).

The public deserves to know the whole truth, not spin or part-truths – both the public interest and the national interest depends on it.

By the New Zealand Defence Force’s own account, it appears reasonable to suggest that the commanders overseeing Operation Burnham had legal obligations to civilians; that they were potentially negligent when considered against their stated rules of engagement, rules of conduct, obligations to international human rights law and international humanitarian law – negligent of their obligations to laws covering war and armed conflict, notwithstanding their obligations as representatives of the people and government of New Zealand to observe the Bill of Rights Act.

It is also reasonable to suggest; there are significant established facts as mentioned above, as put by the New Zealand Defence Force, that require an official investigative response from the New Zealand government.

It is also reasonable to insist that the matter of an absence of consistent fact emitting from the New Zealand Defence Force upon which a reliable opinion can be draw, adds weight to the burden on the Government to establish an inquiry into this matter.

If the New Zealand Prime Minister Bill English elects not to act then it will likely become a matter of political leadership or lack thereof.

If Bill English does not care to act on his office’s public interest obligations, then, it is reasonable to suggest he consider the empirical facts underlying this matter and the impact the matter has on New Zealand’s national interest. Should he fail to do so, this matter potentially could be argued before the International Criminal Court.

*****

Background relevancies

Were NZDF officials and Hit & Run authors describing the same raid? Let’s compare.

“It seems to me,” Lieutenant-General Tim Keating stressed, “that one of the fundamentals, a start point if you like, of any investigation into a crime is to tie the alleged perpetrators of a crime to the scene. Then we would examine the motive and means, and other scene evidence.” – Lieutenant General Tim Keating, 27 March 2017.

On Monday, 27 March 2017 both the Prime Minister Bill English and the Chief of New Zealand Defence Force Lieutenant-General Tim Keating countered details revealed in the book Hit & Run and argued facts stated in the work could not be relied upon because the authors “incorrectly” alleged Operation Burnham took place in Khak Khuday Dad Village and Naik Village deep in the mountainous Baghlan province of Afghanistan – two locations the Defence Force chief insisted his soldiers had never been to.

Lieutenant-General Keating asserted that the New Zealand Defence Force had never been to the two villages (Khak Khuday Dad and Naik) and insisted Operation Burnham took place 2.2 kilometres to the south of where the authors Nicky Hager and Jon Stephenson had marked the location of the villages (specifically on a map published in the book Hit & Run).

Lieutenant-General Keating said: “As you will note from the book, the authors have been precise in locating these villages with geo reference points — so I have no doubt they are very accurate in the villages they are taking their allegations from.

“The villages lie in the Tirgiran Valley some 2 kilometres north from Tirgiran Village. In straight distance this is like comparing the distance from Te Papa to Wellington Hospital. However, if you overlay the elevated terrain, you will see we are talking about two very separated, distinct settlements,” Lieutenant-General Keating said.

Beyond the obvious, it was a staggering claim, especially for those aware the New Zealand Defence Force had insisted one week prior, that its official position remained the same as stated in a media release dated 20 April 2011 that: “On 22 August 2010 New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) elements, operating as part of a Coalition Force in Bamyan province, Afghanistan, conducted an operation against an insurgent group.”

NZDF’s earlier position asserted New Zealand soldiers had not been in Baghlan province on or near 22 August 2010 the night of Operation Burnham. Now, the chief of New Zealand’s armed forces was admitting that they had.

At the press conference on Monday, 27 March 2017, the Chief of New Zealand Defence Force prepared to stake his claim that the book could not be relied on as a factual reference.

Before around 30 journalists, Lieutenant-General Tim Keating pointed to four relevant bullet-points underlying key claims of fact in the book:

- Helicopter landing sites

- Location of houses that were destroyed

- Locations of where civilians were allegedly killed

- Presumed location of an SAS sniper with evidence presented of SAS ammunition and water bottles which were found at the site.

A relationship was drawn between the sniper location and the alleged killing of the individual Islamuddin, the school teacher.

He acknowledged that the book contained a detailed list of those alleged to have been killed or wounded during a military operation in Khak Khuday Dad and Naik villages and a detailed list of the houses destroyed at the two locations.

Lieutenant-General Keating then drove his point home that: “The underlying premise of the book is that New Zealand’s SAS soldiers conducted an operation on Khak Khuday Dad Village and Naik Village…”

“It seems to me,” he stressed, “that one of the fundamentals, a start point if you like, of any investigation into a crime is to tie the alleged perpetrators of a crime to the scene. Then we would examine the motive and means, and other scene evidence.”

Lieutenant-General Keating pivoted. “Let me now talk about the ISAF Operation Burnham in Tirgiran Village.”

The premise of the Chief of Defence Force’s position was; the book Hit & Run described events that may or may not have occurred in Khak Khuday Dad and Naik villages, but that these alleged events had nothing to do with New Zealand Defence Force soldiers as they had never been to the two locations as marked in the book.

Likewise, the Prime Minister, Bill English, said the book got it wrong, that the New Zealand Defence Force had never been to either Khak Khuday Dad Village and Naik Village.

The Prime Minister added: “We believe in the integrity of the Defence Force more than a book that picks the wrong villages.”

For some, it appeared the raid that night as described by the authors could have been committed by another force. For others, it seemed the authors had got a major fact wrong so therefore the remaining claims in the book were moot.

By mid-Wednesday morning, the government and the public found out there was more to it, that the Chief of New Zealand Defence Force was also wrong with regard to his geography.

Unpicking the official line began in earnest late on Tuesday night (28 March 2017) when the lawyers representing the alleged victims of Operation Burnham contacted their clients back in Afghanistan. The purpose of the contact was to identify the exact location of Khak Khuday Dad Village and Naik Village; to confirm or otherwise disprove the existence of “Tirgiran Village” (the NZDF stated official location of Operation Burnham), and to identify and confirm what village or villages are located at the exact co-ordinates as provided by Lieutenant-General Tim Keating in his briefing to New Zealand media.

The lawyers’ clients, represented by a doctor from the region, stated categorically that “Tirgiran Village” (as stated by Lieutenant-General Keating) does not exist. That the region is known as Tirgiran Valley.

The lawyers evaluated from the new information, that to refer to the location of Operation Burnham as Tirgiran Village is like insisting an operation had occurred in Otago City (obviously Otago is a region and a city of that name does not exist, and as such would fail to offer an exact point of reference on a map).

Importantly, the lawyers confirmed, New Zealand Defence Force co-ordinates of where Operation Burnham took place were correct – but that the location was not as the NZDF had stated as “Tirgiran Village” (an incorrect reference to a village that does not exist) but rather marks the geo-locations of where Khak Khuday Dad Village and Naik Village are located.

Specifically, the villagers confirmed the red-rectangle as marked on the NZDF map provided by the Lt. General on Monday, March 27, and referred to as the area specific to Operation Burnham, frames the exact positions of where Khak Khuday Dad and Naik villages are located.

So simply, the book contained a map that placed Khak Khuday Dad and Naik 2.2 kilometres north of their specific real locations. And, the NZDF got it wrong by stating that those two villages were located where the book suggested, and that the village at the centre of Operation Burnham was a different village called Tirgiran Village (again, a place-name that does not exist).

So it turns out, according to those that live in the Tirgiran Valley, the Chief of Defence Force’s statement is incorrect or false; that when NZDF stated as a categorical fact that the New Zealand SAS commandos had never been to Khak Khuday Dad Village nor Naik Village, that that information was false.

At this point politically, it is inescapable that the Prime Minister’s stated position ought to have taken a hit.

Remember back to the Prime Minister’s statement to media on Monday, March 27, 2017 where he pitched his rationale: “We believe in the integrity of the Defence Force more than a book that picks the wrong villages.”

Surely, the same measure that was applied to the authors of Hit & Run now ought to be applied in equal measure to the New Zealand Defence Force chief and his officials. After all, they also got their geography wrong.

Since then, there has been stated unease about the whole issue by Internal Affairs Minister Peter Dunne (the minister who would have to sign off and authorise the costs of an inquiry should the Prime Minister order an inquiry be established). By Thursday, 30 March 201,7 Dunne, through media, called for an inquiry into the whole affair. (ref. Stuff.co.nz )

Also on Thursday, the Minister of Defence at the time of the raid, Dr Wayne Mapp, wrote of his unease about Operation Burnham in a piece published on the Pundit website. (ref. Pundit )

Dr Mapp argued that the government’s position, and that of the New Zealand Defence Force, cannot be the end of it.

“Part of protecting their [the SAS’] reputation is also finding out what happened, particularly if there is an allegation that civilian casualties may have been accidentally caused. In that way we both honour the soldiers, and also demonstrate to the Afghans that we hold ourselves to the highest ideals of respect of life, even in circumstances of military conflict,” wrote Dr Mapp.

Common statements of fact

The descriptions of Operation Burnham, in both the book, and, as stated by the New Zealand Defence Force, do mirror each account with precision on numerous vital points, including:

- The time of night Operation Burnham took place

- That New Zealand Defence Force was commanding and leading the operation (both on the ground and in the air)

- That the helicopters were manned by United States military personnel under New Zealand’s command

- That the purpose of the operation was to kill or capture those named as having been part of a Taliban insurgent raid that killed Lieutenant Tim O’Donnell

- That buildings were destroyed during the operation

- That people were killed at the villages.

However, anyone who has reasonably assessed the issue can see there is much more information to be revealed.

Conclusion

In concluding this analysis, it is an imperative that due to the highest levels of public and national interest concerning the alleged conduct, the seriousness of allegations, and the variables relating to the official account, that the matter be subjected to an independent commission of inquiry.

Selwyn Manning is editor of EveningReport.nz. This analysis was first published on Kiwipolitico.com and on Evening Report and is republished on the sister website Asia Pacific Report with the permission of the author.