By Linawati Sidarto in Amsterdam

A unique photographic exhibition in Amsterdam shows what the Dutch state tried to hide from its people about the grueling war it fought against Indonesia, its former colony.

An Indonesian girl playing a tiny banjo sits among smiling Dutch soldiers on a military vehicle, surrounded by locals. This jovial image belies the fact that the streets of Surakarta, Central Java, on December 21, 1948 the day the photo was shot were deserted as the Dutch had just renewed its military offensive on Java.

“The official image of the war on Java and Sumatra aimed at manipulating public opinion,” said the opening text of the exhibition “Colonial War 1945–1949: Desired and Undesired Images” at Amsterdam’s Dutch Resistance Museum.

“Without images of violence there seemed to be no war.”

During World War II, the Netherlands was occupied by Germany on their home soil and by Japan in their colony of the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch barely had time to savour their freedom after Germany’s surrender in May 1945 when it was jolted by its colony’s independence proclamation on August 17, 1945.

In the next four years, close to 100,000 Dutch soldiers out of a population of just under 10 million were sent off to Indonesia in what the exhibition calls “the biggest war the Dutch had ever fought”. Most of the soldiers were drafted. Almost 6,000 Dutch soldiers lost their lives, while 150,000 Indonesians military and civilian died during the clashes.

The Dutch government, however, did its best to hide the intensity of that war, calling it a politionele actie, police action.

‘Serving the people’

“The government wanted to present the image that their soldiers were serving the people in the colony,” said historian Erik Somers of the Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies NIOD, one of the exhibition’s initiators.

During that war the Dutch military information service DLC, the exhibition explains, “basically decided what could be reported”.

“There were barely any Dutch journalists and photographers in the country [Indonesia] at the time and many areas were extremely dangerous […] people in the Netherlands saw very little pictorial evidence of the violence.”

The exhibition lets the images tell the story: it chronologically goes through the four years of war, with “desired” and “undesired” images put side by side.

One corner, for example, shows photos of Dutch soldiers distributing food to villagers, while the next panel shows unpublished photos of terrified Indonesian prisoners. Or corpses in a ditch.

The censorship went as far as staging pictures, said exhibition co-initiator Louis Zweers.

“There is one photo of a supposedly jubilant local crowd welcoming Dutch soldiers in Malang [East Java]. If you look closely, however, you can see a soldier on the sidelines directing the crowd,” historian Zweers said during a seminar in January at Amsterdam’s Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences KNAW.

Photos that did not pass the censor include one from August 1946, which still had the original caption written by photographer H. Wilmar: “An extremist who fired on our marines from a ditch tried to escape, but was captured by a marine. The marines would possibly take the man as a prisoner to extract information about the enemy”.

“I’d be surprised if this man made it out alive,” commented a visitor at the exhibition, Klaas Westrene, as he scrutinised the photograph. “It’s good that this exhibition sheds some light on this episode.”

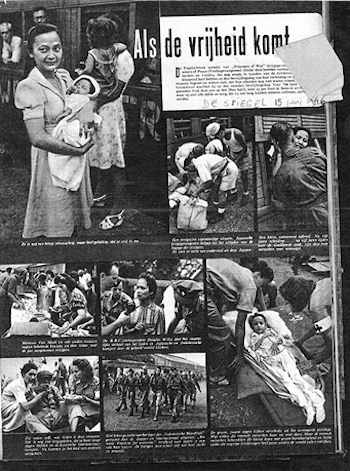

Also on display are illustrated magazines, such as Panorama and De Spiegel,which “showed little of the military operations”, and instead presented “soldiers on patrol, distributing clothes and providing medical care to the native population”.

Somers points out that “there was hardly any reporting in the Dutch press on the euphoric mood among Indonesians regarding their independence [in August 1945]”.

The most stirring part comes at the end of the exposition, where ageing photo albums belonging to soldiers are displayed.

One yellowed page shows small black-and-white photos: first of Indonesian prisoners marching, while the next are of their corpses. The neat hand-written captions read: “There were prisoners being held, but when we’re being fired upon things get nasty, and then some people die”.

Linawati Sidarto is a Jakarta Post contributor in Amsterdam.