ANALYSIS: By Michael Belgrave, Massey University

Australian Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price’s recent claim that New Zealand’s Waitangi Tribunal has veto powers over Parliament was met with surprise in New Zealand, especially by the members of the tribunal itself.

That’s because it is just plain wrong.

As the debate around the Voice to Parliament ramps up, we can probably expect similar claims to be made ahead of this year’s referendum. But the issue is so important to Australia’s future that such misinformation should not go unchallenged.

- READ MORE: What Australia could learn from New Zealand about Indigenous representation

- Solicitor-general confirms Voice model is legally sound, will not ‘fetter or impede’ Parliament

- Explainer: the significance of the Treaty of Waitangi

- What actually is a treaty? What could it mean for Indigenous people?

From an Australian perspective, New Zealand may appear ahead of the game in recognising Indigenous voices constitutionally. But that has certainly not extended to granting a parliamentary power of veto to Māori.

The Waitangi Tribunal was originally established as a commission of inquiry in 1975, given the power only to make recommendations to government. And so it remains. The Crown alone appoints tribunal members and many are non-Māori.

As with all commissions of inquiry, it is up to the government of the day to make a political decision about whether or not to implement those recommendations.

Deceptive and wrong

Price’s claim echoed a February article and paper published by the Institute of Public Affairs, aimed at influencing the Voice referendum. Titled “The New Zealand Māori voice to Parliament and what we can expect from Australia”, it was written by the director of the institute’s legal rights program, John Storey.

The paper makes a number of assertions: the Waitangi Tribunal has a veto over the New Zealand parliament’s power to pass certain legislation; the Waitangi Tribunal was established to hear land claims but its brief has expanded to include all aspects of public policy; and the Waitangi Tribunal “shows the Voice will create new Indigenous rights”.

The last of the statements is deceptive and the others are completely wrong. The Waitangi Tribunal’s jurisdiction was largely set in stone by the New Zealand parliament in 1975 when it was established.

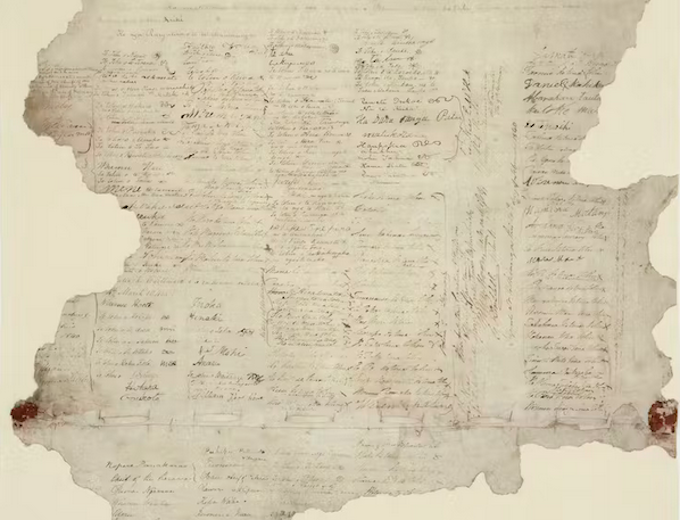

Far from investigating land claims, it initially wasn’t able to examine any claims dating from before 1975. Parliament changed the tribunal’s jurisdiction in 1985, giving it retrospective powers back to 1840 (when the Treaty of Waitangi/te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed).

The tribunal then started hearing land claims. But in its first decade, it focused on fisheries, planning issues, the loss of Māori language, government decisions being made at the time and general issues of public policy.

Historic grievances

Over the past 38 years, the tribunal has focused on what are called “historical Treaty claims”, covering the period 1840 to 1992. In 1992 a major settlement of fishing claims began an era of negotiation and settlement of these claims, quite separate from the tribunal itself.

With the majority of significant historic claims now settled or in negotiation, that aspect of the tribunal’s work is coming to an end. It has returned to hearing claims about social issues and other more contemporary issues.

Far from expanding its jurisdiction, the tribunal’s powers have been steadily reduced in recent decades. In 1993, it lost the power to make recommendations involving private land — that is, land not owned by the Crown.

In 2008, it lost the power to investigate new historical claims, as the government looked to close off new claims that could undermine current settlements.

There is one area where the tribunal was given the power to force the Crown to return land. The 1984-1990 Labour government set a policy to rid itself of what were seen as surplus Crown assets.

A deal was struck between Māori claimants and the Crown to allow the tribunal to make binding recommendations to return land in very special cases.

This compromise was not created by the tribunal but through ambiguity in legislation, which was resolved in favour of Māori claimants in the Court of Appeal. The ability to return land has almost never been used and is being progressively repealed across the country as Treaty settlements are implemented in legislation.

Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price made the erroneous comments while appearing at a debate on the Voice to Parliament referendum in Australia. https://t.co/XGBfteJDaM

— Stuff (@NZStuff) April 27, 2023

Wide political support

Storey quotes a number of tribunal reports, which make findings about the Crown’s responsibilities, as if these findings are binding on the Crown or even on Parliament. This is not the case. The Waitangi Tribunal investigates claims that the Crown has acted contrary to the “principles of the Treaty”.

The Waitangi Tribunal establishes what those principles are, but they are binding on neither the courts nor Parliament. Having made findings, the tribunal makes recommendations — not to Parliament, as Storey suggests, but to ministers of the Crown.

Some recommendations are implemented, others are not.

Where there is a dispute between the Crown and Māori, the tribunal has often recommended negotiation rather than make specific recommendations for redress.

Storey has elsewhere referred to the tribunal as a “so-called advisory, now binding, Māori Voice to Parliament” that has “decreed” certain things. In the longer paper he does admit the “tribunal cannot dictate the exact form any redress offered by government must take”.

But he then falls back on the notion of a “moral veto” — that its status is so elevated that parliament is forced, however reluctantly, to do its bidding.

Yet not only does the Crown ignore tribunal recommendations as it chooses, it refuses even to be bound by the tribunal’s expert findings on history in negotiating settlements.

The Waitangi Tribunal will remain a permanent commission of inquiry because there is wide political support for its work. Nor can be it held solely responsible for increasing Māori assertiveness or political engagement with government, even if this was in any way a bad thing.

A larger social shift has taken place in Aotearoa New Zealand over the past few decades. No fiat from the Waitangi Tribunal has eliminated the cultural misappropriation of Māori faces and imagery — something Storey warns could mean “tea towels with a depiction of Uluru/Ayers Rock, or boomerang fridge magnets, would become problematic”.

The Waitangi Tribunal has often done no more than make Māori histories, Māori perspectives and Māori values accessible to a non-Māori majority. It has certainly had no power to control where debates on Indigenous issues fall.![]()

Dr Michael Belgrave is professor of history, Massey University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.