A new book about one of New Zealand’s foremost peace activists offers insight into Owen Wilkes, the man described as the intellect behind New Zealand’s anti-nuclear stance.

REVIEW: By Pat Baskett

In the days before mobile phones and emails, there were telephone trees. They grew and spread messages like leaves, thriving on the fertile ground of common beliefs and support for a particular cause.

It worked like this: one member of a group phoned 10 others who phoned another 10, each of whom phoned 10 more. On and on . . . The caller was never anonymous, relationships were established — or you simply said, “no thanks”.

The task of spreading information, before the internet, was time-consuming and labour intensive. Photocopiers, which became widely used only in the late 1970s, replaced an invaluable machine called a duplicator. You cranked the handle, one turn for each page, hoping the paper wouldn’t stick. How long did it take to do a thousand?

Next came the mail-out — folding, stuffing envelopes, sticking on stamps if funds allowed, or delivering them by hand into letterboxes.

The process was convivial, the days were busy but there was always time. There needed to be, because the issue was urgent.

The Cold War, that period of perilous mistrust between the communist Soviet Union and the “free” West, led by the United States, engulfed us in fear of a nuclear holocaust. Barely a generation separated us from the end of World War II when nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan.

The mutually assured destruction (MAD) these weapons promised was a fragile pseudo peace. In our neighbourhood peace groups, we understood the devastation a nuclear winter would bring and we worked out the radius of death and damage from a bomb dropped on our own cities.

An essential step

Yet more than nuclear weapons was, and still is, at stake. The movement was called the Peace Movement because banning nukes was considered the essential step in ensuring world peace.

The stockpile of nuclear weapons held by each side was more than enough to eradicate all, or most, life on earth — and it still is.

Those existential threats have a familiar ring, though the cause we face today adds another dimension. So far, the benefits of almost instant communication and dissemination of information haven’t enabled the world to devise for climate disruption what activists, uniquely in New Zealand, achieved — the 1986 nuclear weapons-free legislation.

Passed by the Labour government of David Lange, it prohibits not just weapons but nuclear-powered warships — including those of our former ANZUS allies, namely the United States.

There has never been any question of rescinding this act. It remains in safe obscurity — to such an extent that I wonder how many of our Gen X contemporaries are aware of its existence.

Yet more than nuclear weapons was, and still is, at stake. The movement was called the Peace Movement because banning nukes was considered the essential step in ensuring world peace.

In 1984, 61 percent of the population were living in 86 locally declared nuclear-weapons-free zones. Academic activists came together to form Scientists Against Nuclear Arms (SANA) and Engineers for Social Responsibility (ESR – this group now focuses on the climate disruption).

The medical fraternity formed a local branch of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW).

#PacificMediaWatch ‘Lots of information isn’t secret, it’s just hard to find’ – Nicky Hager on one of #NZ’s most famous #whistleblowers #AsiaPacificReport #Stuff #OwenWilkes #NickyHager #peaceresearch #investigations #militarism #opensource #newbooks https://t.co/7bvE7tR5Qo pic.twitter.com/eCGyH9BKjy

— David Robie (@DavidRobie) January 1, 2023

Extraordinary sleuthing talent

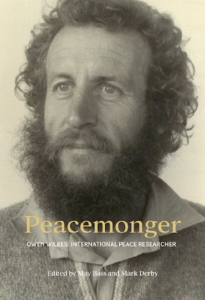

Much of the information which fuelled the work of all these groups was brought to light by the extraordinary sleuthing talent of one man. Owen Wilkes is described as ” . . . the intellect behind New Zealand’s anti-nuclear stance” in a recent book, Peacemonger: Owen Wilkes international peace researcher, published by Raekaihau Press in association with Steele Roberts Aotearoa.

The book consists of 12 essays by friends and collaborators, themselves experts in their individual fields and who leave their own legacies of contribution to the knowledge that led to the anti-nuclear legislation.

They include physicist Dr Peter Wills who was instrumental in setting up SANA and Auckland University’s Centre for Peace Studies; investigative journalist and researcher Nicky Hager; and veteran peace and human rights activist Maire Leadbeater. Two contributions are by Wilkes’s colleagues at the Peace Research Institute in Oslo Norway, Dr Ingvar Botnen and Dr Nils Petter Gleditsch.

Wilkes spent six years from 1976 working in Oslo and also at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

The work is edited by Mark Derby and Wilkes’s partner May Bass. While a traditional biography with a single author may have avoided the repetition of information, the various personal anecdotes and responses result in the portrayal of an unconventional, highly talented individual.

In his introduction, Derby sums up Wilkes’s life: “Although invariably non-violent, politically non-aligned and generally law-abiding, Owen encountered official opposition, harassment and intimidation in various forms as he became internationally known for the quality and impact of his peace research.”

Wilkes was born in Christchurch in 1940 and died in Kawhia in 2005. In his early adult years he worked as an entomologist on various projects supported by the US military, including at McMurdo base in the Antarctic. These, he discovered, were connected with a US military germ warfare project.

Using official information laws

His gift was to see through, and behind, the information government made public about our relationship to our official allies, essentially the US. To do this he used our own official information laws and the American equivalent, plus any public reports to congress and US budget reports he could lay hands on.

Rubbish bags also feature in a couple of accounts.

What now may be stored as megabytes of information consists of boxes and folders of carefully catalogued material, the bulk of which is lodged at the Alexander Turnbull Library (with information also at the university libraries of Auckland and Canterbury).

The truth Wilkes was committed to appears, in retrospect, somehow simpler than that of the struggle towards a fossil-free future and a liveable planet for all. Peace is a part of this and the nukes are still there.

Wilkes documented how in many cases what was billed as civilian also had profound military implications. This was nowhere more clear than in the anti-bases campaign which Murray Horton chronicles — bases being sites in remote locations for monitoring or receiving satellite information, some of which new technology has rendered obsolete.

These include Mt St John near Lake Tekapo and Black Birch near Blenheim, and those still operating at Tangimoana in the Manawatu and at Waihopai, also near Blenheim.

Wilkes’s unconventional appearance and lifestyle — he famously wore shorts in sub-zero temperatures when skiing in Norway — made him a target for accusations of being a communist, a not uncommon slander of the peace movement.

Having sharp eyes

Maire Leadbeater, in her account of his long investigation by the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, suggests his only “crime” was “to have sharp eyes and the ability to put two and two together”.

Yet there were more conventional sides to his interests. One was archaeology, beginning in his 1962 when he worked as a field archaeologist for the Canterbury Museum. This continued after he left the peace movement in the early 1990s and worked for the Waikato Department of Conservation in a variety of jobs including filing archaeological and historical records.

The truth Wilkes was committed to appears, in retrospect, somehow simpler than that of the struggle towards a fossil-free future and a liveable planet for all. Peace is a part of this and the nukes are still there.

- Peacemonger – Owen Wilkes: International Peace Researcher, edited by May Bass and Mark Derby. Published by Raekaihau Press in association with Steele Roberts Aotearoa (2022). This article was first published by Newsroom is republished with the author’s and Newsroom’s permission. Asia Pacific Report editor David Robie is one of the contributing authors.