By Jodesz Gavilan in Manila

A birth of a child usually draws out changes from people. Parents, and even grandparents, recreate themselves in a bid to better address the demands of the new addition to the family.

Julio* knew this all too well. He first became a father at the young age of 17, and went on to work odd jobs to fulfill his responsibilities. But along the way, due to mounting pressure and the vicious cycle of poverty, Julio turned to illegal drugs.

“Sabi niya sa akin hindi ko siya maintindihan kasi ako raw may maayos na trabaho at madali makahanap ng panibagong trabaho kung sakali, samantalang siya, walang ganoong oportunidad para sa kanya,” Cristina, his younger sister, told Rappler in an interview.

(He told me I won’t be able to understand him because I have a stable job and can get another job if I want to, while he doesn’t have that opportunity.)

Julio eventually separated from his first wife, and met a new woman who then got pregnant. With a new baby on the way, 39-year-old Julio was determined more than ever to change.

He planned to start a sari-sari store, buy a refrigerator to sell frozen goods, just about anything to start anew.

“Gusto niya na iyong iyong nagawa niyang pagkukulang sa unang pamilya niya, hindi na ulit mangyari doon sa ipinagbubuntis ng kanyang kinakasama,” Cristina recalled. (He wanted to avoid repeating the same shortcomings he had with his first family.)

But President Rodrigo Duterte had other plans for Julio and thousands of others who came from the poorest communities in the Philippines. Drug dependents, for the country’s chief executive, are hopeless and useless to society.

Enemy out of drug users

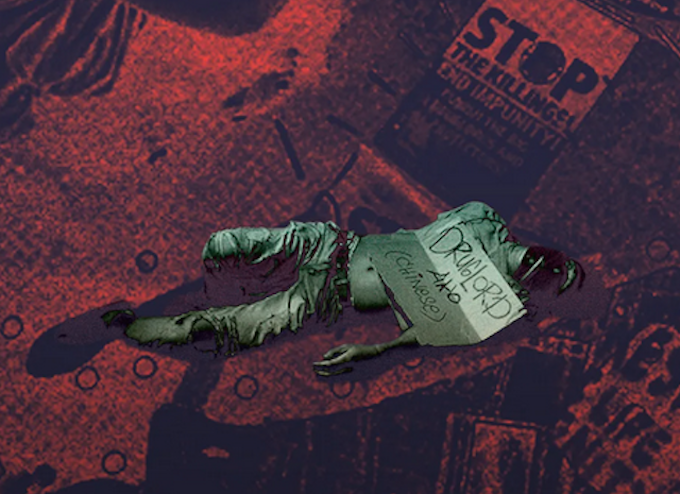

Duterte made an enemy out of drug users and waged a “war” that smudged gutters, roads, and narrow alleys all over the country with blood.

RealNumberPH, the government’s unitary report on the drug war, shows that at least 6248 people have died at the hands of police during anti-illegal drug operations between July 2016 and April 30, 2022, while human rights groups estimate the total death toll to reach 30,000 to include victims of vigilante-style killings.

But figures obtained by Rappler show that the Philippine National Police (PNP) had already recorded 7884 deaths from July 1, 2016 to August 31, 2020.

On December 11, 2018, Julio became one of the thousands slain. One person told his family that their son was standing outside when he and a companion were abducted by men riding a white van.

Their lifeless bodies were found not long after.

Cristina was sure it was the police who killed his brother, but they feared going public with this allegation. It didn’t help that the sole witness, who talked to them during his brother’s funeral, was also eventually killed.

“Masakit ang pagkamatay niya pero iniisip ko na lang na at least nakita at naiburol namin siya, hindi tulad sa iba na nakikita na putol na ang kamay, wala na balita na bigla na lang nawawala,” she said.

(It hurts that he died but at least we were able to find his body and do a proper burial, unlike others who were dismembered or just disappeared completely.)

Duterte’s war on drugs

This is Duterte’s war on drugs, a key policy in his administration that has been scrutinised by both local and international bodies, including the International Criminal Court.

For Gloria Lai, regional director for Asia of the International Drug Policy Consortium, the bloody trail Duterte will leave behind once his presidential term ends on June 30 was highly unnecessary and preventable.

“[Killing people] is not a solution,” she told Rappler.

“What does success look like for the Duterte administration? It kept changing over time [and] there is no way you can say there is success,” Lai added.

The President and his allies’ rhetoric in the past six years would make one think that the Philippines has become a narcostate where drug users are behind the most violent crimes. For Duterte, they steal, they kill, they take innocent lives.

The Philippines indeed has issues with the proliferation of illegal drugs, but determining how widespread it is has been hard under the Duterte administration, given the overall lack of transparency and accurate data.

Duterte himself has been dropping different figures over the years. But a report released in February 2020 by Vice-President Leni Robredo following her short stint as co-chairperson of the Inter-Agency Committee on Anti-Illegal Drugs stated that there “is no common and reliable baseline data on the number of drug dependents in the country.”

‘Keeping their grip on power’

“It really just seemed to serve the administration well… to obtain power, to keep their grip on power, because it creates fear, it creates enemies, it creates scapegoats that justify really brutal and violent actions,” Lai said, adding that the drug issue was “exploited for political gain”.

Six years into the administration, the Duterte government remains tight-lipped, if not vague, about what it deemed key performance indicators of the bloody war on drugs.

PNP spokesperson Colonel Jean Fajardo said the police used two approaches in addressing the drug problem in the country. For the last six years, it had focused on reducing supplies and targeting their so-called pushers, up to high-value individuals.

“Dalawa po ang lagi nating ginagamit na approach dito po sa ating kampanya laban sa ilegal na droga. Ito po ‘yong tinatawag natin na supply reduction strategy and demand reduction strategy,” Fajardo told Rappler.

(We use two approaches in our campaign against illegal drugs. We call them supply reduction and demand reduction strategies.)

But despite this, the PNP and its partner Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) only managed to clear 25,061 out of 35,471 barangays it identified as being involved in illegal drugs. As of April 30, 2022, there are still 10,410 drug-affected barangays yet to be cleared by the PNP and PDEA.

Spike after start of bloody operations

This means, 29.34 percent of drug-affected barangays are yet to be cleared by drug enforcement authorities. Based on data on drug-affected barangays from 2016 to 2022, the Philippines saw a spike in 2017, a year after the start of bloody operations.

From 19,717 drug-affected villages in 2016, the number rose to 24,424 the following year. The number of drug-affected barangays then significantly dropped between 2020 and 2022 — the pandemic years.

In terms of collected illegal drugs, the authorities were able to seize P89.29-billion worth of illegal drugs from July 1, 2016 until April 30, 2022. PDEA, one of the lead agencies for Duterte’s drug war, boasted that they were able to seize 11,843.41 kilograms or P76.55-billion worth of shabu or crystalline methamphetamine.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has yet to release its 2022 report on synthetic drugs in Southeast Asia. But in their 2021 report, the UNODC reported that shabu was the cause of the majority of drug-related arrests and treatment admissions in the Philippines.

For six years, authorities were able to arrest a total of 341,494 individuals. Of this number, only 15,096 are considered high-value targets.

Based on the PNP’s classification, individuals who are considered high-value targets are those who run drug dens, are on the wanted list, and leaders and members of drug groups, among others.

This means that of the total number of arrested individuals due to illegal drug offences, only 4.42 percent or around four in every 100 people arrested are high-value targets.

Dehumanizing rhetoric, actions

Drug users bacame pawns

Duterte used drug users as pawns in his bid to make violence a norm in state policy and actions, Philippine Human Rights Information Center (PhilRights) executive director Nymia Pimentel-Simbulan said.

“The legacy that he will be leaving behind would be institutionalization of state violence, this particular government has a proclivity towards addressing societal problems using a war framework,” she told Rappler in an interview on Monday, June 13.

Staying true to his violent rhetoric, the President has effectively mobilised state resources to use violence and other punitive measures to address issues. Beyond the problem of illegal drugs, this approach can also be seen in the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

If the Duterte government was serious about eradicating drugs in the Philippines, Lai said that it should’ve aimed for programs that better suit this intended outcome instead of focusing on killings.

For one, the state should’ve highlighted how drug addiction is a health problem, therefore producing better health programs. For people who use illegal drugs like shabu to stay awake to work long hours, the government should invest in programs that will keep families out of the vicious cycle of poverty.

But as it is, Duterte’s rhetoric and actions further dehumanize drug dependents, lumping them together with those who are part of the illegal drug syndicates.

“If you forced them and placed them into a list where they could be hunted down and randomly interrogated by police, or even just prevent them from getting a job or going to a certain school, you just drastically diminished their life prospects,” Lai said.

Gap in social response

PNP spokesperson Fajardo admitted that there is still really a gap when it comes to social response, as well as rehabilitation facilities to cater to drug personalities.

“Sinasabi natin, we agree on the fact na ito pong drug problem natin ay health problem. Hindi lang social problem. So ‘yong mga pasilidad kulang, ‘yong ating mga livelihood na pupuwede po nating i-offer dito sa mga sumurrender pati na rin po ‘yong mga nagtutulak, ‘yong mga pusher. Hindi po sa wala, pero kulang po talaga ‘yong efforts,” Fajardo said.

(We say that we agree on the fact that this drug problem is a health problem. Not only social problems. So our facilities are lacking, the livelihood that we can offer for the surrenderees, to pushers. It’s not that we don’t have anything, but the efforts are not enough.)

There are 64 drug rehabilitation centers in the Philippines as of 2021 — 16 under the Department of Health, nine with the local government units, and 39 privately-owned. Together, these facilities have 4840 bed capacity.

In a forum in June 2021, DOH’s Dangerous Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment Programme manager Jose Leabres said there was a need for 11,911 additional in-patient beds for 2021 and 10,629 for 2022.

Data from the Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) shows an increasing number of admissions to care facilities across the country. In 2021, there were at least 2344 new admissions.

A trail of blood

Duterte is leaving Malacañang on June 30 with a trail of blood from people killed in the name of his violent war on drugs. He also leaves behind thousands of orphaned children in the poorest communities, as well as a much more stigmatised issue of drug dependency in the Philippines.

It now falls on president-elect Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. to “address all the harms done by the Duterte administration” on the issue of illegal drugs in the country, according to Lai, as well as giving justice to thousands of victims.

During the campaign season, Marcos said he will continue Duterte’s drug war, but would focus on its being a health issue. He also hinted about shielding it from the International Criminal Court.

Meanwhile, just this June, during courtesy calls with foreign ambassadors, Swedish Ambassador Annika Thunborg said there was a discussion to continue the drug war within the framework of the law and respect for human rights, among others.

PNP spokesperson Fajardo said the incoming administration should put focus on demand reduction.

“Pero ‘yong isa pa pong approach natin na tinatawag po nating demand reduction program, hangga’t may bumibili po, hangga’t may market po ay talagang meron at meron pong sisibol na panibagong players,” she said.

(But the other approach that we call the demand reduction program, until there are people who purchase drugs, until there is a market for them, there will always be new players.)

DRUG WAR DEATHS. Families of victims of drug-related extrajudicial killings and human rights advocates join a Mass at the Commission on Human Rights headquarters in Quezon City.

Not holding her breath

But Simbulan, whose group PhilRights has documented the victims of Duterte’s war on drugs, is not holding her breath, knowing the Marcos family’s track record and his alliance with Duterte.

“I am not that optimistic that it will adopt a different method or approach,” she said. “Chances are, it will adopt the same punitive violent approach in addressing the drug problem in the Philippines.”

IDPC’s Lai, meanwhile, said it’s going to be a massive turnaround if Marcos decides to do away with what Duterte has done. There is nothing preventing the incoming administration from focusing on drug issues, but it has to make sure to alter government response based on evidence and what communities really need, instead of a blanket campaign that puts a premium on killings.

Most importantly, the new administration should focus their resources on areas that would make a difference on people’s lives for the better.

“[They should] consider that in a lot of cases, the drug policies and the drug laws themselves have caused a lot more harm to people and communities than the actual drugs themselves,” Lai said.

* Names have been changed for their protection

Jodesz Gavilan is a Rappler reporter. Republished with permission.