ANALYSIS: By Robert McLachlan, Massey University

As the Glasgow climate summits gets underway, New Zealand’s government has announced a revised pledge, with a headline figure of a 50 percent reduction on gross 2005 emissions by the end of this decade.

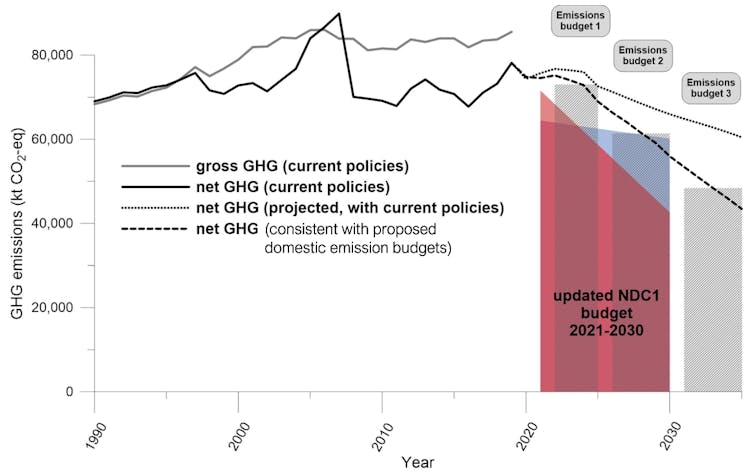

This looks good on the surface, but the substance of this new commitment, known as a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), is best assessed in emissions across decades.

New Zealand’s actual emissions in the 2010s were 701 million tonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent. The carbon budget for the 2020s is 675Mt. The old pledge for the 2020s was 623Mt.

- READ MORE: COP26: time for New Zealand to show regional leadership on climate change

- Electrifying transport: why New Zealand can’t rely on battery-powered cars alone

- Other COP26 climate reports

The Climate Change Commission’s advice was for “much less than” 593Mt, and the new NDC is 571Mt. So yes, the new pledge meets the commission’s advice and is a step up on the old, but it does not meet our fair share under the Paris Agreement.

It is also a stretch to call the new NDC consistent with the goal of keeping global temperature rise under 1.5℃.

True 1.5℃ compliance would require halving fossil fuel burning over the next decade, while the current plan is for cuts of a quarter.

Emissions need to halve this decade

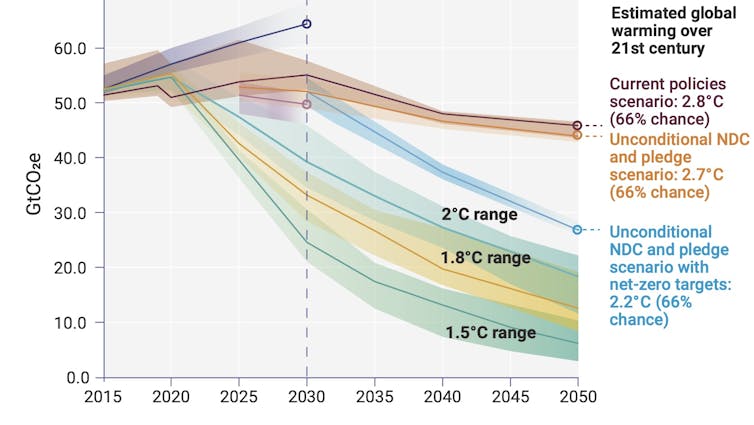

Countries’ climate pledges are at the heart of the Paris Agreement. The initial round of pledges in 2016 added up to global warming of 3.5℃, but it was always intended they would be ratcheted up over time.

In the run-up to COP26, a flurry of new announcements brought that figure down to 2.7℃ — better, but still a significant miss on 1.5℃.

As this graph from the UN’s Emissions Gap Report 2021 shows, the world will need to halve emissions this decade to keep on track for 1.5℃.

New Zealand’s first NDC, for net 2030 emissions to be 30 percent below gross 2005 emissions, was widely seen as inadequate. An update, reflecting the ambition of the 2019 Zero Carbon Act to keep warming below 1.5℃, has been awaited eagerly.

But several factors have combined to make a truly ambitious NDC particularly difficult.

First, New Zealand’s old climate strategy was based on tree planting and the purchase of offshore carbon credits. The tree planting came to and end in the early 2010s and is only now resuming, while the Emissions Trading Scheme was closed to international markets in 2015. The Paris Agreement was intended to allow a restart of international carbon trading, but this has not yet been possible.

Second, New Zealand has a terrible record in cutting emissions so far. Burning of fossil fuels actually increased by 9 percent from 2016 to 2019. It’s a challenge to turn around our high-emissions economy.

Third, our new climate strategy, involving carbon budgets and pathways under advice from the Climate Change Commission, is only just kicking in. The government has made an in-principle agreement on carbon budgets out to 2030, and has begun consultation on how to meet them. The full emissions-reduction plan will not be ready until May 2022.

Regarding a revised NDC, the government passed the buck and asked the commission for advice. The commission declined to give specific recommendations, but advised:

We recommend that to make the NDC more likely to be compatible with contributing to global efforts under the Paris Agreement to limit warming to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels, the contribution Aotearoa makes over the NDC period should reflect a reduction to net emissions of much more than 36 percent below 2005 gross levels by 2030, with the likelihood of compatibility increasing as the NDC is strengthened further.

The government then received advice on what would be a fair target for New Zealand. However, any consideration of historic or economic responsibility points to vastly increased cuts, essentially leading to net-zero emissions by 2030.

Announcing the new NDC, Climate Change Minister James Shaw admitted it wasn’t enough, saying:

I think we should be doing a whole lot more. But, the alternative is committing to something that we can’t deliver on.

What proper climate action could look like

Only about a third of New Zealand’s pledged emissions cuts will come from within the country. The rest will have to be purchased as carbon credits from offshore mitigation.

That’s the same amount (100Mt) that Japan, with an economy 25 times larger than New Zealand’s, is planning to include in its NDC. There is no system for doing this yet, or for ensuring these cuts are genuine. And there’s a price tag, possibly running into many billions of dollars.

New Zealand has an impressive climate framework in place. Unfortunately, just as its institutions are beginning to bite, they are starting to falter against the scale of the challenge.

The commission’s advice to the minister was disappointing. It’s being challenged in court by Lawyers For Climate Action New Zealand, whose judicial review in relation to both the NDC and the domestic emissions budgets will be heard in February 2022.

With only two months to go until 2022 and the official start of the carbon budgets, there is no plan how to meet them. The suggestions in the consultation document add up to only half the cuts needed for the first budget period.

Thinking in the transport area is the furthest advanced, with a solid approach to fuel efficiency already approved, and an acknowledgement total driving must decrease, active and public transport must increase, and new roads may not be compatible with climate targets.

But industry needs to step up massively. The proposed 2037 end date for coal burning is far too late, while the milk cooperative Fonterra — poised to announce a record payout to farmers — intends to begin phasing out natural gas for milk drying only after that date.

The potentially most far-reaching suggestion is to set a renewable energy target. A clear path to 100 percent renewable energy would provide a significant counterweight to the endless debates about trees and agricultural emissions, but it is still barely on the radar.

Perhaps one outcome of the new NDC will be that, faced with the prospect of a NZ$5 billion bill for offshore mitigation, we might decide to spend the money on emissions cuts in Aotearoa instead.![]()

Dr Robert McLachlan is professor in applied mathematics at Massey University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.