By Matthew Scott, reporting for the Pacific Media Centre

The day began with a video, showing a disparate collection of arresting images – the drowned Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira, camera in hand and a huge smile on his face.

Mugshots of two captured French DGSE secret agents – a fake honeymooning pair jailed for manslaughter, but later spirited off to Hao atoll and freedom.

Sun-drenched tropical beaches and a ship with a gaping hull, sinking into the frigid Auckland Harbour on a winter’s night.

READ MORE: 35 years on, Tahiti’s Oscar Temaru guest in Rainbow Warrior rewind

Newspaper headlines expressing disbelief that something like this could happen in peaceful New Zealand.

It is fitting that the discussion began with such an array of images. The bombing of the Rainbow Warrior on 10 July 1985 is one episode in a large and complex geopolitical story – a story that isn’t over yet.

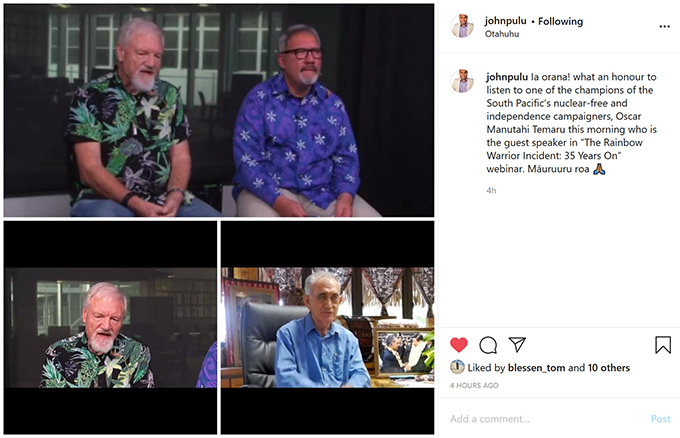

A panel of academics, journalists and activists, each with a connection to the bombing, met via webinar this morning to discuss and mark the 35th anniversary this month.

Suing French government

Organised by H-France, the panel featured figured such as Oscar Temaru, five times president of French Polynesia who is in the process of suing the French government, and Dr David Robie, a New Zealand journalist who was on board the Rainbow Warrior on its final 11 week Pacific voyage to the Marshall Islands and then to New Zealand.

Other speakers were Ena Manuireva, an Auckland University of Technology academic and PhD candidate who is from Mangareva, one of the French Polynesian islands most affected by the French nuclear tests where the Rainbow Warrior intended to protest before its sinking; Stephanie Mills, a former Greenpeace Pacific nuclear test ban campaigner and NZ board chair; and Rebecca Priestley, a history associate professor from Victoria University in Wellington who has specialised in New Zealand’s relationship to nuclear issues.

The webinar was moderated by Dr Roxanne Panchasi, an associate history professor from Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, who specialises in French studies.

The event was preceded by a mihi in Te Reo Māori by Dr Hirini Kaa of the University of Auckland, and a karakia in Tahitian by Ena Manuireva.

In keeping with the discussion’s examination of the effects of colonialism, moderator Dr Panchasi acknowledged the colonised nature of British Columbia, where she was speaking from.

“I am a settler and an uninvited guest on this territory,” she said.

The relevance of the Rainbow Warrior and its connected issues to the current age was a common touchstone among the speakers. Although the sinking of the ship occurred 35 years ago, it still represents issues that have significant impacts on the peoples and nations of the Pacific.

Not least of these are the effects of nuclear testing in French Polynesia.

Nuclear health troubles

Oscar Temaru spoke on how French testing of atomic weapons in his country doesn’t feel so long ago.

“That was 35 years ago?” he said, speaking from his office in Faa’a. “Time flies!”

France conducted 193 tests in French Polynesia between 1966 and 1996, resulting in the contamination of the food and water sources of many people across the islands. Birth defects were common and families were forced to move islands in the hope of providing a healthier future for their children.

To this day, rates of thyroid cancer are disproportionately high, and the disfiguring scars of thyroid removal surgery can be seen on many women.

“I bury people nearly every day, dying from different types of cancer,” Temaru said. “I just wonder sometimes what sin we did to the French.”

Temaru said that nuclear issues and those of French Polynesian sovereignty are interlinked. “The two issues are tied – nuclear testing and our freedom.”

In 2018, he took the French government to the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity, seeking justice for “all the people who died from the consequences of nuclear colonialism”.

Legal troubles

Since then, he has been embroiled in a number of legal troubles leveled at him by the French government, such as a six-month suspended jail sentence and a US$50,000 fine for alleged corruption.

Last month, he embarked on a two-week hunger strike after a French prosecutor ordered the seizure of US$108,000 from him.

Despite these difficulties, Temaru remained upbeat about the future during the webinar. “We need the new generation to take up the flag and go forward,” he said. “Māohi lives matter!”

When the Rainbow Warrior, a 40m trawler owned by Greenpeace, was bombed by French DGSE agents in Auckland Harbour, causing the death of photographer Fernando Pereira, it had set its sights on French Polynesia.

The crew were planning to sail to Moruroa Atoll to protest continued tests.

“The campaign against nuclear testing was in Greenpeace’s DNA,” said former Greenpeace campaigner Stephanie Mills. At the time of the attack, Mills was a reporter for The New Zealand Herald.

But she stressed that the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior was not a discrete, encapsulated event. “People are still dying. They need assistance. There’s still a job to do.”

Birth defects, cancers

Auckland-based researcher Ena Manuireva was born on Mangareva, one of the islands most affected by French testing on Moruroa Atoll. He spoke about how his family was affected by the tests, with a sister born with birth defects and other relatives developing cancer. His mother saw the mushroom cloud from the first blast, in 1967.

“My mum was poisoned,” said Manuireva. “She had her lips bleeding from the fallout.”

Manuireva said that the story was not over for the people of Mangareva, and that they needed to be aware of the ongoing effects of the nuclear blasts.

“People are still dying,” he said. “You see a lot of babies in the cemetery. Mothers and grandmothers feel the effects of chemo and having to take their pills.”

Manuireva said that the people of his island were unwilling to recognise the effects of the tests.

“They feel like they were duped,” he said. Authorities on the island such as the Catholic Church and the French administration assured the locals that the tests would be clean and that there was nothing to worry about, and Manuireva believes that the shame of believing the lies dissuades Mangarevans from talking about these issues.

“We need to make them aware of what’s happened because it’s their history.”

Humanitarian story

New Zealand journalist and academic Dr David Robie, a journalism professor and director of the Pacific Media Centre at AUT, said that media coverage of the attack in New Zealand often neglected to mention the broader issues at play, focusing instead on the espionage intrigue of the DGSE agents.

“I wanted to tell the story from a humanitarian view,” he told the panel.

Dr Robie was onboard the Rainbow Warrior for 11 weeks prior to the bombing, accompanying the crew as they helped residents of the US nuclear test-affected Rongelap Atoll in the Marshall Islands find refuge on Mejato and travelling to New Zealand via Kiribati and Vanuatu.

Helping move the Rongelap refugees was “one of the most momentous and moving experiences I’ve had in my life as a journalist”, he said. He wrote about the experience in his environmental book Eyes of Fire, published in several countries.

Victoria University of Wellington history professor Dr Rebecca Priestley spoke of the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior as confirming New Zealand’s nuclear-free stance.

“The bombing was really the last straw,” she said. In 1984, the Lange-lead Labour government had won on a platform of establishing a nuclear-free zone in the South Pacific.

After tensions with the United States for barring entry of potentially nuclear warships to New Zealand harbours, New Zealand was already in a tense position. The attack caused public outrage and people doubled down on the decision to back nuclear-free.

Evidence-based approach

Priestley spoke about how New Zealand led the world by using an evidence-based decision making approach, and that 2020 and the world-changing crises of covid-19 may ask a similar commitment.

“It was a crazy time in New Zealand and the Pacific’s history,” she said, “and it’s a crazy time now.”

French testing on Moruroa Atoll ended in 1996. Stephanie Mills was at the island with Greenpeace during some of the last tests in 1995. She said that she felt no fear because she knew she had public support behind her, evidenced by a recent petition against the tests that had gathered five million signatures.

“We were tear gassed and boarded. A few of us were taken and disappeared for several days. I wasn’t afraid, because I knew about the five million signatures.”

The change to the regime of nuclear tests in the Pacific was a victory for the people of the region, and Mills said that Greenpeace did not claim credit.

“It was a million acts of courage – an example of change from the bottom up.” She said that remembering the Rainbow Warrior was not just about nuclear issues – “It’s about people having the agency to make change.”

However, new issues assail the Pacific as people living on low-lying islands are some of the first to be affected by the ever-increasing effects of global climate change. This, along with the fact that thousands of people in the Pacific are still affected by the effects of the fallout, means that the Rainbow Warrior remains an important symbol.

Independence a fundamental issue

“The fundamental issue is the self-determination of indigenous peoples across the Pacific,” said Dr Robie. The Rainbow Warrior and its Greenpeace crew, along with their solidarity with independence movements across the Pacific, are inextricable from the issue of indigenous sovereignty.

He invoked the memory of Vanuatu’s founding prime minister Father Walter Lini who said the Pacific could not be truly free until the Māohi people of Tahiti, Kanaks of New Caledonia and West Papuans were also free.

Dr Robie reported that he had noticed a “gap in history” in his students in a “living history” journalism project in 2015, wherein they were not aware of the geopolitical backdrop of the Rainbow Warrior attack. He and Manuireva expressed the desire that this retrospective is the beginning of a series to discuss and raise awareness of related Pacific issues.

While the webinar was concerned with how the event will be remembered into the future, there was also an air of memorial to it. Several of the speakers paid tribute to fallen figures connected to the Rainbow Warrior story.

Chief among these was Fernando Pereira, the sole casualty of the 1985 bombing. “I’d like to acknowledge Fernando Pereira,” said Mills. “He wasn’t just a crew member and photographer. He was a friend to many people.”

Steve Sawyer, the Greenpeace campaigner for the Rongelap mission, was also remembered. Sawyer died almost exactly a year ago, on July 31, 2019, of lung cancer.

Matthew Scott is a student journalist on the Postgraduate Diploma in Communication Studies programme at Auckland University of Technology. He also reports at Te Waha Nui.

This is the second of a series of articles by the Pacific Media Centre’s Pacific Media Watch as part of an environmental project funded by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network (EJN) Asia-Pacific initiative.