Warming beyond 1.5C will unleash a frightening set of consequences and scientists say only a global transformation, beginning now, can avoid it. Climate Home News reviews the warnings in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change research report released yesterday.

Only the remaking of the human world in a generation can now prevent serious, far reaching and once-avoidable climate change impacts, according to the global scientific community.

In a major report released yesterday, the UN’s climate science body found limiting warming to 1.5C, compared to 2C, would spare a vast sweep of people and life on earth from devastating impacts.

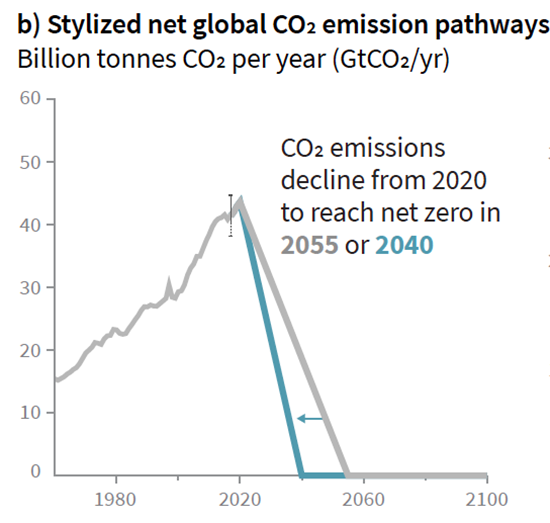

To hold warming to this limit, the scientists said unequivocally that carbon pollution must fall to “net zero” in around three decades: a huge and immediate transformation, for which governments have shown little inclination so far.

READ MORE: Global warming of 1.5C summary for policymakers

“The next few years are probably the most important in our history,” said Debra Roberts, co-chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) research into the impacts of warming.

The report from the IPCC is a compilation of existing scientific knowledge, distilled into a 33-page summary presented to governments. If and how policymakers respond to it will decide the future of vulnerable communities around the world.

“I have no doubt that historians will look back at these findings as one of the defining moments in the course of human affairs,” the lead climate negotiator for small island states Amjad Abdulla said. “I urge all civilised nations to take responsibility for it by dramatically increasing our efforts to cut the emissions responsible for the crisis.”

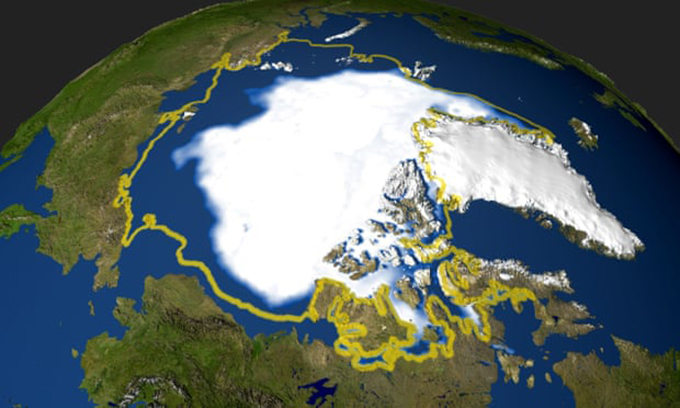

Abdulla is from the Maldives. It is estimated that half a billion people in countries like his rely on coral ecosystems for food and tourism. The difference between 1.5C and 2C is the difference between losing 70-90 percent of coral by 2100 and reefs disappearing completely, the report found.

Small island states

Small island states were part of a coalition that forced the Paris Agreement to consider both a 1.5C and 2C target. Monday’s report is a response to that dual goal. Science had not clearly defined what would happen at each mark, nor what measures would be necessary to stay at 1.5C.

As the report was finalised, the UN Secretary-General’s special representative on sustainable energy Rachel Kyte praised those governments. “They had the sense of urgency and moral clarity,” she said, adding that they knew “the lives that would hang in the balance between 2[C] and 1.5[C]”.

At 2C, stresses on water supplies and agricultural land, as well as increased exposure to extreme heat and floods, will increase, risking poverty for hundreds of millions, the authors said.

Thousands of plant and animal species would see their liveable habitat cut by more than half. Tropical storms will dump more rain from the Philippines to the Caribbean.

“Everybody heard of what happened to Dominica last year,” Ruenna Hayes, a delegate to the IPCC from St Kitts and Nevis, told Climate Home News. “I cannot describe the level of absolute alarm that this caused not only me personally, but everybody I know.”

Around 65 people died when Hurricane Maria hit the Caribbean island in September 2017, destroying much of it.

In laying out what needs to be done, the report described a transformed world that will have to be built before babies born today are middle aged. In that world 70-85 percent of electricity will be produced by renewables.

More nuclear power

There will be more nuclear power than today. Gas, burned with carbon capture technology, will still decline steeply to supply just supply 8 percent of power. Coal plants will be no more. Electric cars will dominate and 35-65 percent of all transport will be low or no-emissions.

To pay for this transformation, the world will have invested almost a trillion dollars a year, every year to 2050.

Our relationship to land will be transformed. To stabilise the climate, governments will have deployed vast programmes for sucking carbon from the air. That will include protecting forests and planting new ones.

It may also include growing fuel to be burned, captured and buried beneath the earth. Farms will be the new oil fields. Food production will be squeezed. Profoundly difficult choices will be made between feeding the world and fuelling it.

The report is clear that this world avoids risks compared to one that warms to 2C, but swerves judgement on the likelihood of bringing it into being. That will be for governments, citizens and businesses, not scientists, to decide.

During the next 12 months, two meetings will be held at which governments will be asked to confront the challenge in this report: this year’s UN climate talks in Poland and at a special summit held by UN secretary general Antonio Guterres in September 2019.

The report’s authors were non-committal about the prospects. Jim Skea, a co-chair at the IPCC, said: “Limiting warming to 1.5C is possible within the laws of chemistry and physics but doing so would require unprecedented changes.”

‘Monumental goal’

Peter Frumhoff, director of science and policy at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) and a former lead author of the IPCC, said: “If this report doesn’t convince each and every nation that their prosperity and security requires making transformational scientific, technological, political, social and economic changes to reach this monumental goal of staving off some of the worst climate change impacts, then I don’t know what will.”

The scientist have offered a clear prescription: the only way to avoid breaching the 1.5C limit is for humanity to cut its CO2 emissions by 45 percent below 2010 levels by 2030 and reach “net-zero” by around 2050.

But global emissions are currently increasing, not falling.

The EU, one of the most climate progressive of all major economies, aims for a cut of around 30 percent by 2030 compared to its own 2010 pollution and 77-94 percent by 2050. It is currently reviewing both targets and says this report will inform the decisions.

If the EU sets a carbon neutral goal for 2050 it will join a growing group of governments seemingly in line with a mid-century end to carbon – including California (2045), Sweden (2045), UK (2050 target under consideration) and New Zealand (2050).

But a fundamental tenet of climate politics is that expectations on nations are defined by their development. If the richest, most progressive economies on earth set the bar at 2045-2050, where will China, India and Latin America end up? If the EU aims for 2050, the report concludes that Africa will need to have the same goal.

Some of the tools needed are available, they just need scaling up. Renewable deployment would need to be six times faster than it is today, said Adnan Z Amin, the director-general of the International Renewable Energy Agency. That was “technically feasible and economically attractive”, he added.

Innovation, social change

Other aspects of the challenge require innovation and social change.

But just when the world needs to go faster, the political headwinds in some nations are growing. Brazil, home to the world’s largest rainforest, looks increasingly likely to elect the climate sceptic Jair Bolsonaro as president.

The world’s second-largest emitter – the US – immediately distanced itself from the report, issuing a statement that said its approval of the summary “should not be understood as US endorsement of all of the findings and key messages”.

It said it still it intended to withdraw from the Paris Agreement.

The summary was adopted by all governments at a closed-door meeting between officials and scientists in Incheon, South Korea that finished on Saturday. The US sought and was granted various changes to the text. Sources said the interventions mostly helped to refine the report. But they also tracked key US interests – for example, a mention of nuclear energy was included.

Sources told CHN that Saudi Arabia fought hard to amend a passage that said investment in fossil fuel extraction would need to fall by 60 percent between 2015 and 2050. The clause does not appear in the final summary.

But still, according to three sources, the country has lodged a disclaimer with the report, which will not be made public for months. One delegate said it rejected “a very long list of paragraphs in the underlying report and the [summary]”.

Republished under a Creative Commons licence.