ANALYSIS: By Pat Walsh

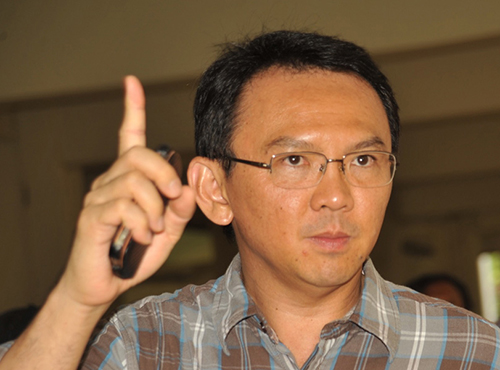

The recent sentencing of Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama, the Christian Chinese-Indonesian Governor of Jakarta, to two years in jail for blasphemy will leave many people in the Asia-Pacific region confounded if not, sadly, further averse to Indonesia.

The court’s decision is not a small thing. Jakarta alone has a population roughly that of New South Wales and Victoria in Australia combined – and more than double the entire population of New Zealand.

Jailing its governor is the equivalent of putting an Australian state premier or the New Zealand prime minister behind bars, conceivable only for the most egregious of crimes.

When the official in question is also widely admired for his competency, opposition to corruption, and drive to reform the massive mess which is Jakarta, one could be forgiven for assuming his blasphemy must have been of medieval proportions.

Did he denounce Islam as “evil’ like the American evangelist Franklin Graham? Did he publicly denounce God as ‘stupid’ like Stephen Fry, now the subject of investigation for blasphemy by the Irish police?

On the contrary. Ahok is deeply respectful of Islam and has many Muslim supporters. Though a Christian, he is also impressively Islam-literate and can quote the Koran, an unusual ability for a Christian.

Ironically, it is this knowledge that worked against him. He asked an Indonesian audience not to be persuaded to vote against him by opponents who claimed the Koran prohibits Muslims from voting for non-Muslims. The implication that leaders should be chosen for their competence not their religion or ethnic background will sound like common sense rather than blasphemy to most people.

Huge numbers mobilised

But extreme Muslims claimed his comment vilified the Koran and that voting for an infidel is apostasy. Their campaign mobilised huge numbers, mainly from outside Jakarta, and resulted in Ahok losing the recent election for the governorship — and his freedom.

Unless his appeal to the Supreme Court succeeds, the blasphemy finding also means he will be banned for life from running for public office.

The affair has already done a serious disservice to Indonesia. It presents Indonesia as fanatical, racist and sectarian. While these perceptions are patently unfair, the affair also reveals some aspects of contemporary Indonesia that are obscured by Canberra’s often lavish praise of our important neighbour.

Radical Islam is increasing in strength and confidence in Indonesia. “Be careful what you wish for,” an Indonesian academic said to me during the anti-democratic Suharto years.

He went on to observe that democracy would allow Muslim organisations sidelined during the Suharto years to operate freely and accept generous funding from benefactors like the Saudi regime whose King Salman recently made a historic visit to Indonesia. The majority of Muslims are moderate and disagree with the hard right but the Ahok case shows that, in a country of 240 million people, a minority can comprise millions and exercise significant political influence.

This influence extends to the nominally independent judiciary whose pronouncement on Ahok is widely considered to have been dictated by the protesters. In effect Ahok was “lynched”.

Aggressive sectional politics

Most fair-minded people in Indonesia and beyond, not least in places like England and Wales where blasphemy laws have been abolished, would struggle to see what was blasphemous about Ahok’s reference to the Koran. The court put aggressive sectional politics ahead of its duty to comply with the rule of law and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to which post-Suharto Indonesia is a signatory.

As with Indonesia’s mock trials on human rights violations in East Timor when the court absolved the powerful military, the court has compromised its independence and bowed to external pressure.

The sidelining of Ahok also demonstrates the continuing power of entrenched political and economic interests in Indonesia. Ahok stood for clean government. He is a vigorous opponent of corruption, a vice roundly condemned in the Koran. Arguably Ahok’s opposition to this Indonesian curse should have earned the admiration of all Muslims, not jail.

Ahok’s removal is also a victory for Prabowo Subianto, recently headlined by The Age as Indonesia’s possible next president. The ex-general’s candidate beat Ahok in the governship elections, thereby delivering Prabowo a major platform from which to conduct his assault on the presidency, currently held by Joko Widodo, himself a former governor of Jakarta.

The Age reported that Prabowo forbids the killing of insects on his ranch. Timorese would laugh in disbelief. Their truth commission report lists him as having command responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the many years he was active in East Timor.

The Catholic archbishop of Jakarta has publicly condemned growing fundamentalism and intolerance in Indonesia and the Protestant Council of Churches has called for Ahok’s release and the revocation of the blasphemy law.

Nuns, priests, seminarians and laity have rallied in support of Ahok. One sincerely hopes that the Supreme Court will overrule in Ahok’s favour and that the campaign to scrap the blasphemy law will succeed.

Both measures would do much to restore faith in Indonesia and its future.

Pat Walsh is a human rights activist and former adviser to the Timor-Leste Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation. He co-founded Inside Indonesia magazine.