SPECIAL REPORT: By Jason Brown

Fast-paced electronic music pumps in the background as a rapid montage of moving images flash across the screen.

In a 20 second video, French sailors hunker down in an inflatable speeding over swells.

Another sailor, in bright red shorts, is lowered from a helicopter onto the vessel’s back deck. Captured crew with faces blurred are held in a galley, as bags full of drugs are pulled from below deck and loaded onto pallets for lift-off.

- READ MORE: Lack of investigation into cocaine vessel could hamper regional drug mapping, expert warns

- Other Pacific drug reports

“Throwback to the latest drug seizure at sea by the French Navy, as if you were part of it,” reads the social media caption from French armed forces, documenting last month’s drug seizure by the frigate Prairial.

What the video does not show

French sailors dropping 4.87 tonnes of cocaine into the ocean near the Tuamotu group, north-east of Tahiti. Tossing drugs overboard may be a time-honoured tactic for drug smugglers at sea — but a new one for authorities.

“This record seizure is a successful outcome of the new territorial plan to combat narcotics developed by the High Commissioner of the Republic in French Polynesia,” reads a statement on their website.

Record seizure — worth at least US$150 million — and record disposal, in record time.

One raising questions worldwide.

Why?

“Why won’t France open an investigation after the seizure of these 5 tons of cocaine?” reads the January 20 headline in the French edition of Huffington Post.

Prosecutors in Tahiti emphasised the costs faced by French Polynesia if it were to prosecute all drug traffickers.

“Our primary mission is to prevent drugs from entering the country and to combat trafficking in Polynesia,” said Public Prosecutor Solène Belaouar. As “more and more traffickers transit through our waters we must address the issue of managing this new flow.”

Belaouar told French media that prosecuting drug cases locally costs 12,000 French Pacific Francs a day, or about US$120 per person.

This new concern about costs came as the French territory winds up another drug trafficking case. Under those estimates, the conviction of 14 Ecuador sailors caught smuggling in December 2024 would represent around US$600,000.

Last Thursday, they had their appeal against trafficking 524 kilos on the MV Raymi dismissed, meaning their jail sentences of six to eight years are confirmed. Costs of this case compare with the US$93 million spent between 2013 and 2017 constructing a new prison, Tatutu de Papeari, with a capacity of 410 inmates in Tahiti.

A question sent via social media about the drug dump went unanswered by ALPACI, Amiral commandant la zone maritime de l’océan Pacifique.

Overall, drug seizures by French forces worldwide have increased dramatically.

A total of 87.6 tons of drugs were seized in 2025 in cooperation with state services, including local police, customs and the French Anti-Drug and Smuggling Office (OFAST), nearing twice the previous record of 48.3 tons set the year before, in 2024.

Those statistics seem unlikely to quieten concerns about the new cost-cutting strategy.

Sunny day

Boarded on a sunny day on January 16, the MV Raider carried a crew of 10 Honduran citizens, with one from Ecuador. All faced lengthy jail terms if convicted.

Instead, French authorities let all 11 go, allowing the crew to resume their journey on the offshore supply ship. That decision contrasts with the high-profile approach sometimes taken when it comes to illegal fishing boats, with many captured and resold or set on fire and sunk at sea.

Dozens of public social media comments in French Polynesia and the Cook Islands questioned the disposal of the drugs at sea, with some calling for the ship’s seizure. Tahiti news media were the first to question the decision to catch and release.

“4.87 tonnes of cocaine . . . but no legal action taken,” Tahiti Nui Television noted as the news broke a few days later.

At first, French authorities claimed the seizure took place in international waters or the “high seas”.

Lead prosecutor Belaouar told TNTV that “Article 17 of the Vienna Convention stipulates that the navy can intercept a vessel on the high seas, check its flag of origin, ask the Public Prosecutor, and the High Commissioner is involved in the decision, if they agree that the procedure should not be pursued through the courts, and that it should therefore be handled solely administratively.”

However, TNTV also quoted legal sources as stating the drug seizure of 96 bales took place within the “maritime zone” of French Polynesia.

Ten days after first reports of the seizure, Belaouar was no longer talking about the “high seas”, instead claiming the need for a new strategy to handle drug flows.

Drug ‘superhighway’

“The Pacific has become a superhighway for drugs”, Belaouar asserted, adding that “70 percent of cocaine trafficking passes through this route.”

Those differing claims raised questions in Tahiti, and 1100 km to the south-west, when the briefly seized vessel, the MV Raider, turned up off Rarotonga broadcasting a distress signal.

Customs officials told daily Cook Islands News the vessel was reporting engine trouble, and confirmed MV Raider was the same vessel that had been intercepted by French naval forces with the drugs on board.

Live maritime records also show the tug supply boat as “anchored” at Rarotonga.

Aptly named, the Raider caught official attention before passing through the Panama Canal, with a listed destination of Sydney Australia.

Anonymous company

Sending a small coastal boat some 14,000 km across the world’s largest ocean drew attention on a route more usually plied by container ships up to nine times longer.

Also raising questions — the identity of the ship owners.

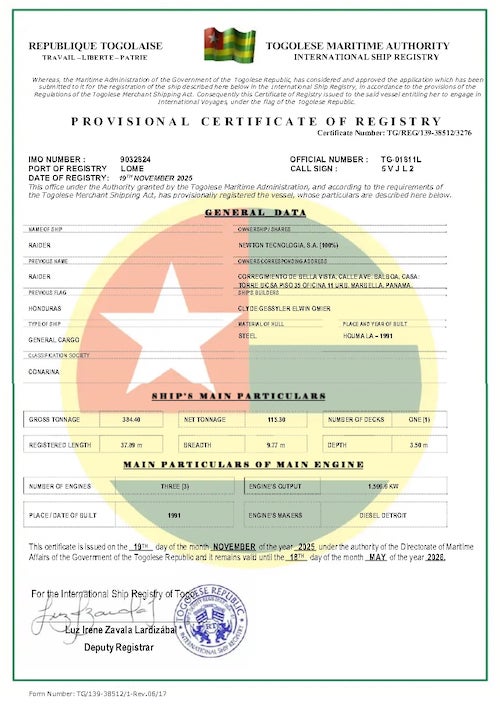

A signed certificate uploaded online by an unofficial source appears to show that the last known ownership traces to an anonymous Panama company named Newton Tecnologia SA.

That name also appears in a customer ranking report from the Panama Canal Authority, with Newton Tecnologia appearing at 541 of 550 listed companies.

Under Panama law, Sociedad Anonomi — anonymous “societies” or companies — do not need to reveal shareholders, and can be 100 percent foreign owned.

A review of various databroker services show one of the company directors as Jacinto Gonzalez Rodriguez.

A person of the same name is listed on OpenCorporates in a variety of leadership roles with 22 other companies in Panama, including engineering, marketing, a “bike messenger” venture, and as treasurer and director for an entity called “Mistic La Madam Gift Shop.”

However, Newton Tecnologia SA does does not show up in the same database, or searches of the country’s official business registry.

A similarly named company is registered in Brazil but is focused on educational equipment, not shipping, with one director showing up in search results at community art events.

‘Dark fleet’

Registered with the International Marine Organisation under call sign 5VJL2, the MV Raider is described as a “Multi Purpose Offshore Vessel” with IMO number: 9032824.

Online records indicate that the ship was built in 1991 in the United States, with a “Provisional Certificate of Registry” from the Togo Maritime Authority dated only two months ago, on 19 November 2025. With a declared destination of Sydney, Australia, the Raider and its Togo certificate are valid until 18 May 2026.

According to maritime experts, provisional certification is a red flag that allows what industry sources term the “dark fleet” to exploit open registries. This “allows entry on a temporary basis (typically three to six months) with minimal due diligence pending submission of all documentation,” according to a 2025 review from Windward, a marine risk consultancy.

“Vessels then ‘hop’ to another flag before the provisional period expires.”

Where there’s smoke

Windward listed Togo as being among ship registries that flagged ships with little to no oversight, along with Antigua and Barbuda, Azerbaijan, Barbados, Belize, Cameroon, Comoros, Djibouti, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Honduras, Hong Kong, Liberia, Mongolia, Oman, Panama, San Marino, São Tomé and Príncipe, St. Kitts and Nevis, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Vietnam.

In the Pacific, other registries noted by Windward as failing basic enforcement include Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Palau, Tuvalu and Vanuatu.

Previously registered in Honduras, the July 2023 edition of the Worldwide Tug and OSV News reports that GIS Marine LLC, a Louisiana company, sold the Raider in 2021 to an “undisclosed” interest in Honduras.

Other records indicate GIS Marine acted as managers but the actual owner was a company called International Marine in Valetta, Malta. The only company with a similar name at that address, International Marine Contractors Ltd, is shown as inactive since 2021.

For now, though, the Raider is among tens of thousands of ships operating worldwide with “provisional certification” — allowing ships to potentially skip regulations requiring expensive maintenance and repair.

That may have been the case for the Raider, with Rarotonga residents filming what one described as “smoke” rising from the ship a day after issuing a distress call.

Where there’s drug smoke, there’s usually a bonfire of questions afterwards.

Including from José Sousa-Santos, associate professor of practice and head of the University of Canterbury’s Pacific Regional Security Hub, who told Cook Islands News that since the vessel was intercepted in French Polynesian waters “it falls under French legal jurisdiction”.

Jason Brown is founder of Journalism Agenda 2025 and writes about Pacific and world journalism and ethically globalised Fourth Estate issues. He is a former co-editor of Cook Islands Press.