ANALYSIS: By Ben Bohane

This week Cambodia marks the 50th anniversary of the fall of Phnom Penh to the murderous Khmer Rouge, and Vietnam celebrates the fall of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces in April 1975.

They are being commemorated very differently; after all, there’s nothing to celebrate in Cambodia. Its capital Phnom Penh was emptied, and its people had to then endure the “killing fields” and the darkest years of its modern existence under Khmer Rouge rule.

Over the border in Vietnam, however, there will be modest celebrations for their victory against US (and Australian) forces at the end of this month.

Yet, this week’s news of Indonesia considering a Russian request to base aircraft at the Biak airbase in West Papua throws in stark relief a troubling question I have long asked — did Australia back the wrong war 63 years ago? These different areas — and histories — of Southeast Asia may seem disconnected, but allow me to draw some links.

Through the 1950s until the early 1960s, it was official Australian policy under the Menzies government to support The Netherlands as it prepared West Papua for independence, knowing its people were ethnically and religiously different from the rest of Indonesia.

They are a Christian Melanesian people who look east to Papua New Guinea (PNG) and the Pacific, not west to Muslim Asia. Australia at the time was administering and beginning to prepare PNG for self-rule.

The Second World War had shown the importance of West Papua (then part of Dutch New Guinea) to Australian security, as it had been a base for Japanese air raids over northern Australia.

Japanese beeline to Sorong

Early in the war, Japanese forces made a beeline to Sorong on the Bird’s Head Peninsula of West Papua for its abundance of high-quality oil. Former Australian prime minister Gough Whitlam served in a RAAF unit briefly stationed in Merauke in West Papua.

By 1962, the US wanted Indonesia to annex West Papua as a way of splitting Chinese and Russian influence in the region, as well as getting at the biggest gold deposit on earth at the Grasberg mine, something which US company Freeport continues to mine, controversially, today.

Following the so-called Bunker Agreement signed in New York in 1962, The Netherlands reluctantly agreed to relinquish West Papua to Indonesia under US pressure. Australia, too, folded in line with US interests.

That would also be the year when Australia sent its first group of 30 military advisers to Vietnam. Instead of backing West Papuan nationhood, Australia joined the US in suppressing Vietnam’s.

As a result of US arm-twisting, Australia ceded its own strategic interests in allowing Indonesia to expand eastwards into Pacific territories by swallowing West Papua. Instead, Australians trooped off to fight the unwinnable wars of Indochina.

To me, it remains one of the great what-ifs of Australian strategic history — if Australia had held the line with the Dutch against US moves, then West Papua today would be free, the East Timor invasion of 1975 was unlikely to have ever happened and Australia might not have been dragged into the Vietnam War.

Instead, as Cambodia and Vietnam mark their anniversaries this month, Australia continues to be reminded of the potential threat Indonesian-controlled West Papua has posed to Australia and the Pacific since it gave way to US interests in 1962.

Russian space agency plans

Nor is this the first time Russia has deployed assets to West Papua. Last year, Russian media reported plans under way for the Russian space agency Roscosmos to help Indonesia build a space base on Biak island.

In 2017, RAAF Tindal was scrambled just before Christmas to monitor Russian Tu95 nuclear “Bear” bombers doing their first-ever sorties in the South Pacific, flying between Australia and Papua New Guinea. I wrote not long afterwards how Australia was becoming “caught in a pincer” between Indonesian and Russian interests on Indonesia’s side and Chinese moves coming through the Pacific on the other.

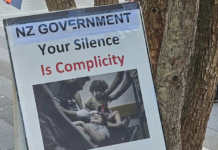

All because we have abandoned the West Papuans to endure their own “slow-motion genocide” under Indonesian rule. Church groups and NGOs estimate up to 500,000 Papuans have perished under 60 years of Indonesian military rule, while Jakarta refuses to allow international media and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to visit.

Alex Sobel, an MP in the UK Parliament, last week called on Indonesia to allow the UN High Commissioner to visit but it is exceedingly rare to hear any Australian MPs ask questions about our neighbour West Papua in the Australian Parliament.

Canberra continues to enhance security relations with Indonesia in a naive belief that the nation is our ally against an assertive China. This ignores Jakarta’s deepening relations with both Russia and China, and avoids any mention of ongoing atrocities in West Papua or the fact that jihadi groups are operating close to Australia’s border.

Indonesia’s militarisation of West Papua, jihadi infiltration and now the potential for Russia to use airbases or space bases on Biak should all be “red lines” for Australia, yet successive governments remain desperate not to criticise Indonesia.

Ignoring actual ‘hot war’

Australia’s national security establishment remains focused on grand global strategy and acquiring over-priced gear, while ignoring the only actual “hot war” in our region.

Our geography has not changed; the most important line of defence for Australia remains the islands of Melanesia to our north and the co-operation and friendship of its peoples.

Strong independence movements in West Papua, Bougainville and New Caledonia all materially affect Australian security but Canberra can always be relied on to defer to Indonesian, American and French interests in these places, rather than what is ultimately in Australian — and Pacific Islander — interests.

Australia needs to develop a defence policy centred on a “Melanesia First” strategy from Timor to Fiji, radiating outwards. Yet Australia keeps deferring to external interests, to our cost, as history continues to remind us.

Ben Bohane is a Vanuatu-based photojournalist and policy analyst who has reported across Asia and the Pacific for the past 36 years. His website is benbohane.com This article was first published by The Sydney Morning Herald and is republished with the author’s permission.