By Brooklyn Self, Queensland University of Technology

Gendered online violence is silencing women journalists in Fiji, says Pacific media scholar Dr Shailendra Singh.

The harmful trend involves unwanted private messages, hateful language and threats to reputation, often from anonymous sources.

The visibility of women journalists has made them frequent targets, while perpetrators can harness popular online platforms to shame or embarrass them in the public eye.

Dr Singh has dedicated extensive research to this dangerous phenomenon, including a 2022 study with Geraldine Panapasa and other colleagues from The University of South Pacific and Fiji Women’s Rights Movement.

The research found 83 percent of female Fijian journalists who completed their survey had experienced online harassment.

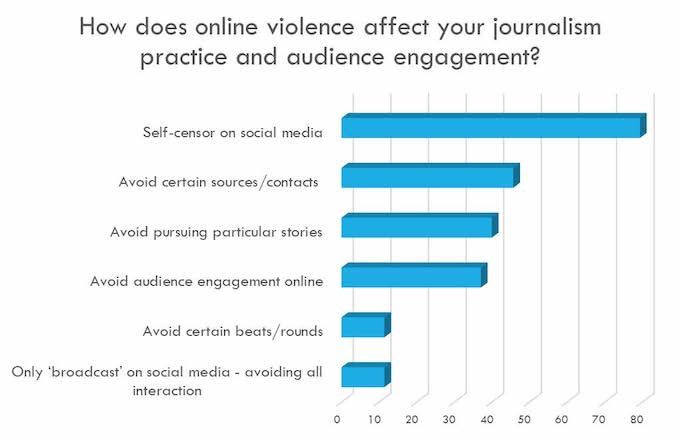

Significantly, the women journalists reported changes to their journalistic practice because of abuse, such as self-censoring their content or avoiding certain sources or stories.

“The aim is to embarrass female journalists into silence, or punish them for writing a report that someone did not like,” Dr Singh says.

The researchers said the valuable role of the Fourth Estate in protecting the public interest makes harassment of journalists a critical concern.

Eliminating the problem will need further action, as 40 per cent of the women journalists who responded said their employers had no systems in place for dealing with online violence.

Islands Business magazine manager Samantha Magick says her staff can come to her for support, but even so, harassment adds another barrier to attracting and keeping journalists in the industry.

“We’re competing with marketing, or competing with UN agencies that will snap up a great young communications officer after they’ve done a year in a newsroom, and pay them a lot more,” she says.

“The people who stick with the profession are either super passionate about it and willing to sacrifice certain things or are in a position where it can be viable for them.”

Fiji adopted its Online Safety Act in 2018, which bans harmful online communications and appoints the Online Safety Commission to investigate offences.

Fiji TV news editor Felix Chaudhary says journalists often do not report online abuse because of a lack of faith or awareness around reporting procedures.

“You can have the best laws, but if you aren’t able to enforce the law or have reporting mechanisms in place, then the laws are useless because they’re not going to serve their purpose,” he says.

Until these mechanisms are developed, media employers should build a zero-tolerance workplace culture and establish their own protocols to deal with online violence, Chaudhary says.

“You get very clear from the beginning that you will not tolerate any form of harassment – abuse, verbal, written online,” he says. “So it’s very clear from the get-go that kind of behaviour is not accepted.”

There is a growing body of data to suggest women’s online safety is a critical concern across Fiji, with research from the Online Safety Commission revealing that 61.44 per cent of women in Fiji experienced cyberbullying in 2023.

Chaudhary says the online harassment of women journalists reflects ongoing issues for women that stem from the explosion of internet use in Fiji.

“Facebook, Twitter and Instagram gave people open territory to abuse anyone and everyone at will, whenever they wanted to.

“I think there should have been a lot of education on social media etiquette, what’s acceptable and what’s not,” he says.

- Fijians can directly report online violence on social media platforms or lodge a complaint with the Fiji Online Safety Commission: https://osc.com.fj/

Brooklyn Self is a student journalist from the Queensland University of Technology who travelled to Fiji with the support of the Australian Government’s New Colombo Plan Mobility Programme. This article is republished by Asia Pacific Report in collaboration with the Asia Pacific Media Network (APMN), QUT and The University of the South Pacific.