Last week, the UN’s highest court issued a stinging ruling that countries have a legal obligation to limit climate change and provide restitution for harm caused, giving legal force to an idea that was hatched in a classroom in Port Vila. This is how a group of young students from Vanuatu changed the face of international law.

SPECIAL REPORT: By Jamie Tahana for RNZ Pacific

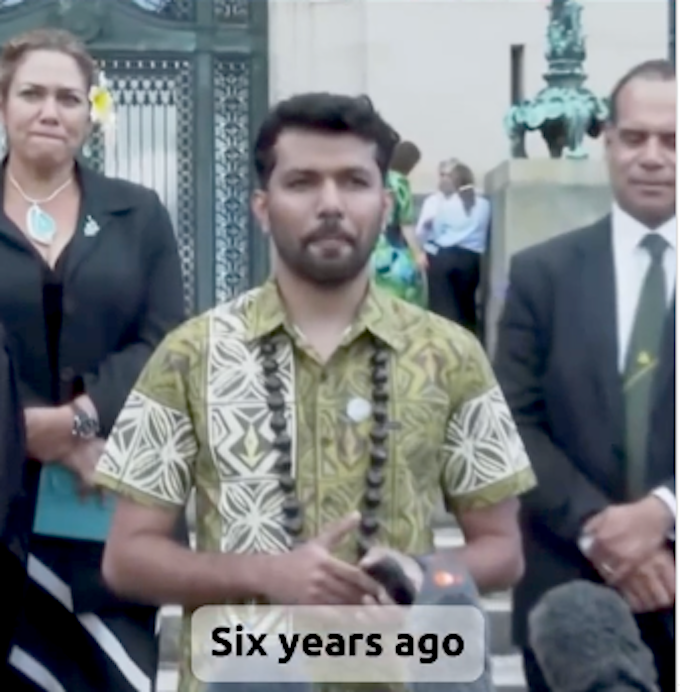

Vishal Prasad admitted to being nervous as he stood outside the imposing palace in the Hague, with its towering brick facade, marble interiors and crystal chandeliers.

It had taken more than six years of work to get here, where he was about to hear a decision he said could throw a “lifeline” to his home islands.

The Peace Palace, the home of the International Court of Justice, could not feel further from the Pacific.

Yet it was here in this Dutch city that Prasad and a small group of Pacific islanders in their bright shirts and shell necklaces last week gathered before the UN’s top court to witness an opinion they had dreamt up when they were at university in 2019 and managed to convince the world’s governments to pursue.

“We’re here to be heard,” said Siosiua Veikune, who was one of those students, as he waited on the grass verge outside the court’s gates. “Everyone has been waiting for this moment, it’s been six years of campaigning.”

What they wanted to hear was that more than a moral obligation, addressing climate change was also a legal one. That countries could be held responsible for their greenhouse gas emissions — both contemporary and historic — and that they could be penalised for their failure to act.

“For me personally, [I want] clarity on the rights of future generations,” Veikune said. “What rights are owed to future generations? Frontline communities have demanded justice again and again, and this is another step towards that justice.”

And they won.

The court’s president, Judge Yuji Iwasawa, took more than two hours to deliver an unusually stinging advisory opinion from the normally restrained court, going through the minutiae of legal arguments before delivering a unanimous ruling which largely fell on the side of Pacific states.

“The protection of the environment is a precondition for the enjoyment of human rights,” he said, adding that sea-level rise, desertification, drought and natural disasters “may significantly impair certain human rights, including the right to life”.

After the opinion, the victorious students and lawyers spilled out of the palace alongside Vanuatu’s Climate Minister, Ralph Regenvanu. Their faces were beaming, if not a little shellshocked.

“The world’s smallest countries have made history,” Prasad told the world’s media from the palace’s front steps. “The ICJ’s decision brings us closer to a world where governments can no longer turn a blind eye to their legal responsibilities”.

“Young people around the world stepped up, not only as witnesses to injustice, but as architects of change”.

A classroom exercise

It was 2019 when a group of law students at the University of the South Pacific’s campus in Port Vila, the harbourside capital of Vanuatu, were set a challenge in their tutorial. They had been learning about international law and, in groups, were tasked with finding ways it could address climate change.

It was a particularly acute question in Vanuatu, one of the countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis. Many of the students’ teenage years had been defined by Cyclone Pam, the category five storm that ripped through much of the country in 2015 with winds in excess of 250km/h.

It destroyed entire villages, wiped out swathes of infrastructure and crippled the country’s crops and water supplies. The storm was so significant that thousands of kilometres away, in Tuvalu, the waves it whipped up displaced 45 percent of the country’s population and washed away an entire islet.

Cyclone Pam was meant to be a once-in-a-generation storm, but Vanuatu has been struck by five more category five cyclones since then.

Among many of the students, there was a frustration that no one beyond their borders seemed to care particularly much, recalled Belyndar Rikimani, a student from Solomon Islands who was at USP in 2019. She saw it as obscene that the communities with the smallest carbon footprint were paying the steepest price for a crisis they had almost no hand in creating.

Each year the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was releasing a new avalanche of data that painted an increasingly grim prognosis for the Pacific. But, Rikimani said, the people didn’t need reams of paper to tell them that, for they were already acutely aware.

On her home island of Malaita, coastal villages were being inundated with every storm, the schools of fish on which they relied were migrating further away, and crops were increasingly failing.

“We would go by the sea shore and see people’s graves had been taken out,” Rikimani recalled. “The ground they use to garden their food in, it is no longer as fertile as it has once been because of the changes in weather.”

The mechanism used by the world to address climate change is largely based around a UN framework of voluntary agreements and summits — known as COP — where countries thrash out goals they often fail to meet. But it was seen as impotent by small island states in the Pacific and the Caribbean, who accused the system of being hijacked by vested interests set on hindering any drastic cuts to emissions.

So, the students argued, what if there was a way to push back? To add some teeth to the international process and move the climate discussion beyond agreements and adaptation to those of equity and justice? To give small countries a means to nudge those seen to be dragging their heels.

“From the beginning we were aware of the failure of the climate system or climate regime and how it works,” Prasad, who in 2019 was studying at the USP campus in Fiji’s capital, Suva, told me.

“This was known to us. Obviously there needs to be something else. Why should the law be silent on this?”

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the main court for international law. It adjudicates disputes between nations and issues advisory opinions on big cross-border legal issues. So, the students wondered, could an advisory opinion help? What did international law have to say about climate change?

Unlike most students, who would leave such discussions in the classroom, they decided to find out. But the ICJ does not hear cases from groups or individuals; they would have to convince a government to pursue the challenge.

Together, they wrote to various Pacific governments hoping to discuss the idea. It was ambitious, they conceded, but in one of the regions most threatened by rising seas and intensifying storms, they hoped there would at least be some interest.

But rallying enough students to join their cause was the first hurdle.

“There was a lot of doubts from the beginning,” Rikimani said. “We were trying to get the students who could, you know, be a part of the movement. And it was hard, it was too big, too grand.”

In the end, 27 people gathered to form the genesis of a new organisation: Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change (PISFCC).

A couple of weeks went by before a response popped up in their inboxes. The government of Vanuatu was intrigued. Ralph Regenvanu, who was at that time the foreign minister, asked the students if they would like to swing by for a meeting.

“I still remember when [the] group came into my office to discuss this. And I felt solidarity with them,” Regenvanu recalled last week.

“I could empathise with where they were, what they were doing, what they were feeling. So it was almost like the time had come to actually, okay, let’s do something about it.”

The students — “dressed to the nines,” as Regenvanu recalled — gave a presentation on what they hoped to achieve. Regenvanu was convinced. Not long after the wider Vanuatu government was, too. Now it was time for them to convince other countries.

“It was just a matter of the huge diplomatic effort that needed to be done,” Regenvanu said. “We had Odi Tevi, our ambassador in New York, who did a remarkable job with his team. And the strategy we employed to get a core group of countries from all over the world to be with us.

“It’s interesting that, you know, some of the most important achievements of the international community originated in the Pacific,” Regenvanu said, citing efforts in the 20th century to ban nuclear testing, or support decolonisation.

“We have this unique geographic and historic position that makes us able to, as small states, have a voice that’s much louder, I think. And you saw that again in this case, that it’s the Pacific once again taking the lead to do something that is of benefit to the whole world.”

What Vanuatu needed to take the case to the ICJ was to garner a majority of the UN General Assembly — that is, a majority of every country in the world — to vote to ask the court to answer a question.

To rally support, they decided to start close to home.

Hope and disappointment

The students set their sights on the Pacific Islands Forum, the region’s pre-eminent political group, which that year was holding its annual leaders’ summit in Tuvalu. A smattering of atolls along the equator which, in recent years, has become a reluctant poster child for the perils of climate change.

Tuvalu had hoped world leaders on Funafuti would see a coastline being eaten by the ocean, evidence of where the sea washes across the entire island at king tide, or saltwater bubbles up into gardens to kill crops, and that it would convince the world that time was running out.

But the 2019 Forum was a disaster. Pacific countries had pushed for a strong commitment from the region’s leaders at their retreat, but it nearly broke down when Australia’s government refused to budge on certain red lines. The then-prime minister of Tuvalu, Enele Sopoaga, accused Australia and New Zealand of neo-colonialism, questioning their very role in the Forum.

“That was disappointing,” Prasad said. “The first push was, okay, let’s put it at the forum and ask leaders to endorse this idea and then they take it forward. It was put on the agenda but the leaders did not endorse it; they ‘noted’ it. The language is ‘noted’, so it didn’t go ahead.”

Another disappointment came a few months later, when Rikimani and another of the students, Solomon Yeo, travelled to Spain for the annual COP meeting, the UN process where the world’s countries agree their next targets to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

But small island countries left angry after a small bloc derailed any progress, despite massive protests.

That was an eye-opening two weeks in Madrid for Rikimani, whose initial scepticism of the system had been validated.

“It was disappointing when there’s nothing that’s been done. There is very little outcome that actually, you know, safeguards the future of the Pacific,” she said.

“But for us, it was the COP where there was interest being showed by various young leaders from around the world, seeing that this campaign could actually bring light to these climate negotiations.”

By now, Regenvanu said, that frustration was boiling over and more countries were siding with their campaign. By the end of 2019, that included some major countries from Europe and Asia, which brought financial and diplomatic heft. Other small-island countries from Africa and the Caribbean had also joined.

“Many of the Pacific states had never appeared before the ICJ before. So [we were] doing write shops with legal teams from different countries,” he said.

“We did write shops in Latin America, in the Caribbean, in the Pacific, in Africa, getting people just to be there at the court to present their stories, and then of course trying to coordinate.”

Meanwhile, Prasad was trying to spread word elsewhere. The hardest part, he said, was making it relevant to the people.

International law, The Hague, the Paris Agreement and other bureaucratic frameworks were nebulous and tedious. How could this possibly help the fisherman on Banaba struggling to haul in a catch?

They spent time travelling to villages and islands, sipping kava shells and sharing meals, weaving a testimony of Indigenous stories and knowledge.

In Fiji, he said, the word for land is vanua, which is also the word for life.

“It’s the source of your identity, the source of your culture. It’s this connection that the land provides the connection with the past, with the ancestors, and with a way of life and a way of doing things.”

He travelled to the village of Vunidologa where, in 2014, its people faced the rupture of having to leave their ancestral lands, as the sea had marched in too far. In the months leading up to the relocation, they held prayer circles and fasted. When the day came, the elders wailed as they made an about two kilometre move inland.

“That’s the element of injustice there. It touches on this whole idea of self-determination that was argued very strongly at the ICJ, that people’s right to self-determination is completely taken away from them because of climate change,” Prasad said.

“Some have even called it a new face of colonialism. And that’s not fair and that cannot stand in 2025.”

Preparing the case

If 2019 was the year of building momentum, then a significant hurdle came in 2020, when the coronavirus shuttered much of the world. COP summits were delayed and the Pacific Islands Forum postponed. The borders of the Pacific were sealed for as long as two years.

But the students kept finding ways to gather their body of evidence.

“Everything went online, we gathered young people who would be able to take this idea forward in their own countries,” Prasad said.

On the diplomatic front, Vanuatu kept plugging away to rally countries so that by the time the Forum leaders met again — in 2022 — they were ready to ask for support again.

“It was in Fiji and we were so worried about the Australia and New Zealand presence at the Forum because we wanted an endorsement so that it would send a signal to all the other countries: ‘the Pacific’s on board, let’s get the others’,” Prasad recalled.

“We were very worried about Australia, but it was more like if Australia declines to support then the whole process falls, and we thought New Zealand might also follow.”

They didn’t. In an about-turn, Australia was now fully behind the campaign for an advisory opinion, and the New Zealand government was by now helping out too. By the end of 2022, several European powers were also involved.

Attention now turned to developing what question they wanted to actually ask the international court. And how would they write it in such a way that the majority of the world’s governments would back it.

“That was the process where it was make and break really to get the best outcome we could,” said Regenvanu.

“In the end we got a question that was like 90 percent as good as we wanted and that was very important to get that and that was a very difficult process.”

By December 2022, Vanuatu announced that it would ask the UN General Assembly to ask the International Court of Justice to weigh what, exactly, international law requires states to do about climate change, and what the consequences should be for states that harm the climate through actions or omissions.

More lobbying followed and then, in March 2023, it came to a vote and the result was unanimous. The UN assembly in New York erupted in cheers at a rare sign of consensus.

“All countries were on board,” said Regenvanu. “Even those countries that opposed it [we] were able to talk to them so they didn’t oppose it publicly.”

They were off to The Hague.

A tense wait

Late last year, the court held two weeks of hearings in which countries put forth their arguments. Julian Aguon, a Chamorro lawyer from Guam who was one of the lead counsel, told the court that “these testimonies unequivocally demonstrate that climate change has already caused grievous violations of the right to self-determination of peoples across the subregion.”

Over its deliberations, the court heard from more than 100 countries and international organisations hoping to influence its opinion, the highest level of participation in the court’s history. That included the governments of low-lying islands and atolls, which were hoping the court would provide a yardstick by which to measure other countries’ actions.

They argued that climate change threatened fundamental human rights — such as life, liberty, health, and a clean environment — as well as other international laws like those of the sea, and those of self-determination.

In their testimonies, high-emitting Western countries, including Australia, the United States, China, and Saudi Arabia maintained that the current system was enough.

It’s been a tense and nervous wait for the court’s answer, but they finally got it last Wednesday.

“We were pleasantly surprised by the strength of the decision,” Regenvanu said. “The fact that it was unanimous, we weren’t expecting that.”

The court said states had clear obligations under international law, and that countries — and, by extension, individuals and companies within those countries — were required to curb emissions. It also said the environment and human rights obligations set out in international law did indeed apply to climate change, and that countries had a right to pursue restitution for loss and damage.

The opinion is legally non-binding. But even so, it carries legal and political weight.

Individuals and groups could bring lawsuits against their own countries for failing to comply with the court’s opinion, and states could also return to the ICJ to hold each other to account, something Regenvanu said Vanuatu wasn’t ruling out. But, ultimately, he hoped it wouldn’t reach that point, and the advisory opinion would be seen as a wake-up call.

“We can call upon this advisory opinion in all our negotiations, particularly when countries say they can only do so much,” Regenvanu said. “They have said very clearly [that] all states have an obligation to do everything within their means according to the best available science.

“It’s really up to all countries of the world — in good faith — to take this on, realise that these are the legal obligations under custom law. That’s very clear. There’s no denying that anymore.

“And then discharge your legal obligations. If you are in breach, fix the breach, acknowledge that you have caused harm. Help to set it right. And also don’t do it again.”

Vishal Prasad still hadn’t quite processed the whole thing by the time we met again the next morning. In shorts, t-shirt, and jandals, he cut a much more relaxed figure as he reclined on a couch sipping a mug of coffee. His phone had been buzzing non-stop with messages from around the world.

“Oh, it definitely does not feel real. I don’t think it’s settled in,” he said. “I got, like, a flood of messages, well wishes. People say, ‘you guys have changed the world’. I think it’s gonna take a while.”

He was under no illusions that there was a long road ahead. The court’s advisory came at a time when international law and multilateralism was under particular strain.

When the urgency of the climate debate from a few years ago appears to have given way to a new enthusiasm for fossil fuel in some countries. He had no doubt the Pacific would continue to lead those battles.

“People have been messaging me that across the group chats they’re in, there’s this renewed sense of courage, strength and determination to do something because of what the ICJ has said,” he said.

“I’ve just been responding to messages and just saying thanks to people and just talking to them and I think it’s amazing to see that it’s been able to cause such a shift in the climate movement.”

Watching the advisory opinion being read out at 3am in Honiara was Belyndar Rikimani, hunched over a live stream in the dead of the night.

“What’s very special about this campaign is that it didn’t start with government experts, climate experts or policy experts. It started with students.

“And these law students are not from Harvard or Cambridge or all those big universities, but they are students from the Pacific that have seen the first-hand effects of climate change. It started with students who have the heart to see change for our islands and for our people.”

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.