ANALYSIS: By Patrick Decloitre, RNZ Pacific correspondent French Pacific desk

Another church has been set alight in New Caledonia, confirming a trend of arson which has already destroyed five Catholic churches and missions over the past two months.

The latest fire took place on Sunday evening at the iconic Saint Denis Church of Balade, in Pouébo, on the northern tip of the main island of Grande Terre.

The fire had been ignited in at least two locations — one at the main church entrance and the other on the altar, inside the building.

The attack is highly symbolic: this was the first Catholic church established in New Caledonia, 10 years before France “took possession” of the South Pacific archipelago in 1853.

It was the first Catholic settlement set up by the Marist mission and holds stained glass windows which have been classified as historic heritage in New Caledonia’s Northern Province.

Those stained glasses picture scenes of the Marist fathers’ arrival in New Caledonia.

Parts of the damages include the altar and the main church entrance door.

In other parts of the building, walls have been tagged.

A team of police investigators has been sent on location to gather further evidence, the Nouméa Public Prosecutor said.

250 years after Cook’s landing

The fire also comes as 250 years ago, on 5 September 1774, British navigator James Cook, aboard the vessel Resolution, made first landing in the Bay of Balade after a Pacific voyage that took him to Easter Island (Rapa Nui), the Marquesas islands (French Polynesia), the kingdom of Tonga and what he called the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu).

It was Cook who called the Melanesian archipelago “New Caledonia”.

Both New Caledonia and the New Hebrides were a direct reference to the islands of Caledonia (Scotland) and the Hebrides, an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland.

Five churches targeted

Since mid-July, five Catholic sites have been fully or partially destroyed in New Caledonia.

This includes the Catholic Mission in Saint-Louis (near Nouméa), a stronghold still in the hands of a pro-independence hard-line faction (another historic Catholic mission settled in the 1860s and widely regarded as the cradle of New Caledonia’s Catholicism); the Vao Church in the Isle of Pines (off Nouméa), and other Catholic missions in Touho, Thio (east coast of New Caledonia’s main island) and Poindimié.

Another Catholic church building, the Church of Hope in Nouméa, narrowly escaped a few weeks ago and was saved because one of the parishioners discovered packed-up benches and paper ready to be ignited.

Since then, the building has been under permanent surveillance, relying on parishioners and the Catholic church priests.

The series of targeted attacks comes as Christianity, including Roman Catholicism, is the largest religion in New Caledonia, where Protestants also make up a large proportion of the group.

Each attack was followed by due investigations, but no one has yet been arrested.

Nouméa Public Prosecutor Yves Dupas told local media these actions were “intolerable” attacks on New Caledonia’s “most fundamental symbols”.

Why the Catholic church?

Several theories about the motives behind such attacks are invoking some sort of “mix-up” between French colonisation and the advent of Christianity in New Caledonia.

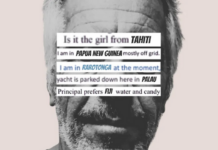

Nouméa Archbishop Michel-Marie Calvet, 80, himself a Marist, said “there’s been a clear determination to destroy all that represents some kind of organised order”

“There are also a lot of amalgamations on colonisation issues,” he said.

“But we’ve seen this before and elsewhere: when some people want to justify their actions, they always try to re-write history according to the ideology they want to support or believe they support.”

While the first Catholic mission was founded in 1853, the protestant priests from the London Missionary Society also made first contact about the same time, in the Loyalty Islands, where, incidentally, the British-introduced cricket still remains a popular sport.

On the protestant side, the Protestant Church of Kanaky New Caledonia (French: Église Protestante de Kanaky Nouvelle-Calédonie, EPKNC), has traditionally positioned itself in an open pro-independence stance.

For a long time, Christian churches (Catholic and Protestants alike) were the only institutions to provide schooling to indigenous Kanaks.

‘Paradise’ islands now ‘closest to Hell’

A few days after violent and deadly riots broke out in New Caledonia, under a state of emergency in mid-May, Monsignor Calvet held a Pentecost mass in an empty church, but relayed by social networks.

At the time still under the shock from the eruption of violence, he told his virtual audience that New Caledonia, once known in tourism leaflets as the islands “closest to paradise”, had now become “closest to Hell”.

He also launched a stinging attack on all politicians there, saying they had “failed their obligations” and that from now on their words were “no longer credible”.

More recently, he told local media:

“There is a very real problem with our youth. They have lost every landmark. The saddest thing is that we’re not only talking about youth. There are also adults around who have been influencing them.

“What I know is that we Catholics have to stay away from any form of violence. This violence that tries to look like something it is not.

“It is not an ideal that is being pursued, it is what we usually call ‘the politics of chaos’.”

Declined Pope’s invitation to Port Moresby

He said that although he had been invited to join Pope Francis in Port Moresby during his current Asia and Pacific tour he had declined the offer.

“Even though many years ago, I personally invited one of his predecessors, Pope John Paul II, to come and visit here. But Pope Francis’s visit [to PNG], it was definitely not the right time,” he said.

Monsignor Calvet was ordained priest in April 1973 for the Society of Mary (Marist) order.

He arrived in Nouméa in April 1979 and has been Nouméa’s Archbishop since 1981.

He was also the chair of the Pacific Episcopal Conference (CEPAC) between 1996 and 2003, as well as the vice-president of the Federation of Oceania Episcopal Conferences (FCBCO).

In 1988, charismatic pro-independence leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou, as head of the FLNKS (Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front), signed the Matignon-Oudinot Accords with then French Prime Minister Michel Rocard, putting an end to half a decade of quasi civil war.

One year later, he was gunned down by a member of the radical fringe of the pro-independence movement.

Tjibaou was trained as a priest in the Society of Mary order.

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.