By Blessen Tom, RNZ journalist

A new production called Coolie: The Story of the Girmityas is shedding light on the lesser-known history of the Indian indentured labourers.

Poet and music producer Nadia Freeman’s latest work gives life to the hidden voice of her Indo-Fijian ancestors through electronic music and theatre.

“I just felt like I was losing more of my ancestry and my ethnicity, and I wanted to look more into it to understand,” Freeman says.

The show opened on Thursday at the Kia Mau contemporary Māori, Pasifika and indigenous arts festival.

“Coolie”, which is used in the production’s title, was a derogatory term used by British colonial supervisors when addressing the workers in Fiji.

“I want people who are outside that community to know what happened, to know more about,” she said.

Who were the Girmityas?

The Indian workers were called the Girmityas, which in Hindi means “agreement”. The agreement was initially for five years, but it was extendable.

On finishing five years abroad, they were permitted to return to India at their own expense or serve 10 more years and return at the expense of the British colonial government.

Some workers returned home, but many could not afford the return journey and were stuck in Fiji.

“We are still quite an angry community … angry because we haven’t healed,” says businessman and community advocate Nik Naidu.

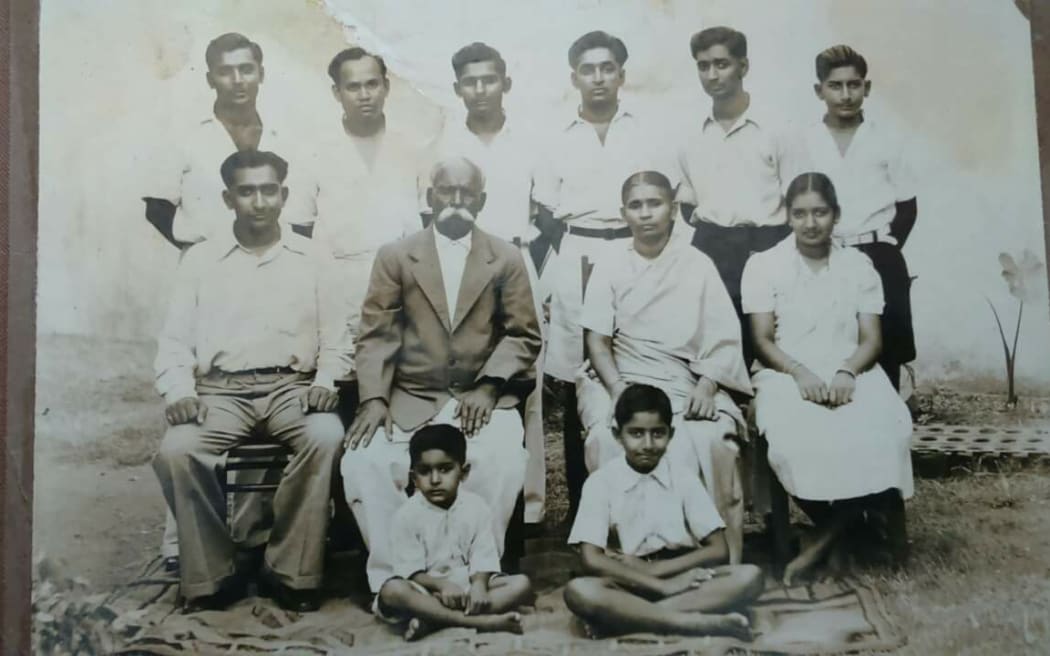

His grandfather, M.N. Naidu, was an indentured labourer who was on a ship to Fiji in the early 1900s.

Like many Indians who were sent to Fiji, Naidu’s grandfather was also looking for a better life.

“They were living in dire poverty and were looking for money to support their families, so that’s how my grandfather got on the ship,” Naidu says.

Challenging life

Life in Fiji was challenging.

The journey took months, and many did not even make it to Fiji. That was not the end of their struggles.

“There was hardship and there were difficulties,” Naidu says.

“In the beginning, it was the harshness of plantation life, poor living conditions, you know, resettlement, displacement, realisation of not being able to return, inability to participate in their religion properly, and, you know, the caste system that existed, the difficulties and, of course, lack of women.”

Finding a companion was a challenge for many young Girmits. The disproportionate sex ratio meant there were only 40 women for every 100 men.

Journalist Sri Krishnamurthi has also heard many stories about the Girmityas from his grandparents.

Working sugar canefields

“My grandmother, Bonamma, came from India with my grandfather and came to work in the sugar canefields under the indentured system,” Krishnamurthi says.

“They lived in ‘lines’ — a row of one-room houses. They worked the cane fields from 6am to 6pm largely without a break. It was basically slavery in all but name.”

Krishnamurthi remembers the story about his grandfather, who was sent back to India, “because he thumped a coolumbar sahib” (a white man on horseback who made sure the work was done) who was whipping the workers.

Naidu says: “I wasn’t fortunate enough to meet my grandfather. I was 2 years old when he passed away and he went back to India and passed away in India.”

His family is now running the organisations that his father started, including schools.

“The colonial administration at the time did not want to educate the Fijian Indians,” he says.

“They wanted them to stay in servitude, as small farmers who were always dependent on the sugar cane plantations and uneducated.”

Addressing new challenges

A few weeks ago, the community celebrated the 144th Girmit Remembrance Day in New Zealand.

“We remembered our forefathers, who had contributed towards this development of the Fiji Indian community,” says Krish Naidu, president of the Fiji Girmit Foundation.

“It is a day where we honour and remember their struggles and sacrifices, but we also celebrate their resilience.

“It’s important our young people in particular actually understand who we are, where we come from.”

In 2023, a new challenge emerged for the Indo-Fijian community in New Zealand. The government’s decision to classify them as Asians rather than Pacific Islanders is stirring criticism within the community.

“Because we, as people with Indian biological traits, are not considered by the Ministry of Pacific,” Naidu says.

Naidu thinks that the government’s move is “unfair”.

“We get emails and messages from students because they miss out on specific scholarships,” he says.

However, he was delighted for the newly announced Girmit Day, a national holiday in Fiji.

“We were the actual architects of it because we’ve been pushing for the holiday since 2015 in Fiji,” he says.

“We are absolutely overjoyed.”

This article is republished under a community partnership agreement with RNZ.