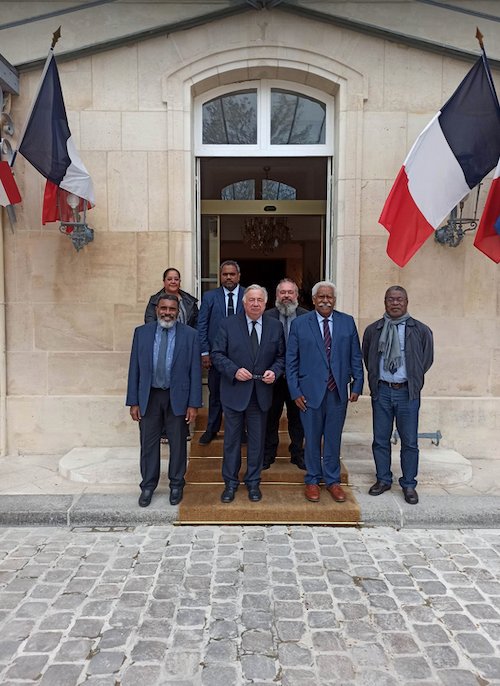

Brief reports have surfaced about the separate bilateral meetings of the Kanaky New Caledonia pro- and anti- independence representatives with French Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne in Paris last week. Here the leader of the Front de Liberation Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS) delegation, Roch Wamytan, outlines their case as presented to Prime Minister Borne at the Hôtel Matignon on 11 April 2023.

By Roch Wamytan, leader of the FLNKS delegation

First of all, allow me, Madam Prime Minister, to greet you on behalf of the Front de Liberation Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS) delegation for this first meeting with you.

Despite the difficult situation prevailing in France, you were able to take some time in your busy schedule to discuss with our delegation and we recognise your significant consideration of the situation of New Caledonia (NC). We have also had the opportunity to communicate with you by phone with some of our delegation members and I thank you.

Today is the first time that we meet, and it is important to be able to discuss face-to-face and try to understand each other. It is a huge responsibility has been passed on to you, that of an ancient civilization characterised as “the Kanak people of Melanesian and Austronesian descent” which has been present in the Caledonian archipelago for more than 3000 years.

Close to 250 years ago (1774), this ancient people crossed the path of Europeans through James Cook, and then that of the French on September 24, 1853, the date of the possession of the islands by France. It is from this time onward that the chaotic history of relations between France and us, the Kanak people, began.

Almost 170 years later, we are still debating these relations that bind us: You as the representative of France, and us, the members of the FLNKS delegation, led by two of the signatories of the Nouméa Agreement, Victor Tutugoro and myself, accompanied by Gilbert Tyuienon, Mickaël Forrest, Jean Pierre Djaïwé, Digoue, Aloisio Sako, Jean Creugnet and our technical team.

As you know, Madam Prime Minister, the FLNKS represents the national liberation movement of the colonised Kanak people, since the re-inscription in 1986 of New Caledonia on the United Nations’ list of countries to decolonise. Therefore, we stand in front of you as the representative of the governing authority of France, according to international law.

On February 26, 2023, the popular congress of the FLNKS and the nationalist and Indigenous movement has validated the unique and unitary trajectory for the country’s achievement of full sovereignty and independence, through negotiation with the governing authority, France, which is the governing power since the possession of New Caledonia on September 24, 1853.

For 170 years (September 24, 1853) we have lived under the governance of France, which has become since 1986 the administering power of the New Caledonia, the latter being considered a non-self-governing territory. This governance has never been accepted by our people and the genealogy of the struggle to free ourselves of it is well known. Allow me to share some key dates:

● From 1774 (arrival of James Cook) to 1853 (formal possession): People had to struggle against the harmful effects of microbial epidemics introduced by the first Europeans, faced with a population which lacked immunity. As a result, close to 90 percent of the population was eradicated. Survivors organised themselves and survived thanks to their ancestral resilience when faced with diseases and European invasion. Then, colonisation followed.

● From 1853 to 1924: The violent possession of land, the settlement of convicts and deportees, the revolts of chiefdoms and the bloody repression of the colonial army with its massacres, ethnocide, population displacement and transportation.

● From 1925 to 1946: The population reaches its lowest point, approximately 25,000 people. It is the point of departure for a rebirth, through reconstruction, the restructuring of chiefdoms with catholic and protestant missions.

● From 1945 to 1946: New Caledonia misses its first opportunity to achieve independence. Indeed, the President of the United States of America, [Franklin D.] Roosevelt, was of the idea that the French defeat would de facto, lead to the end of its empire, then in ruin. He was therefore planning on changing the status of Dakar, Indochina and other French possessions and was advising France to progressively give up its

possessions in Asia and Africa.

When it came to New Caledonia, this colony was to be removed from France and placed under the governance of the USA, similarly to Palau, before giving it its independence back. That is what the work of Marie Claude Smouts, researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), shows in her book La France à l’ONU.

● From 1946 to 1958: It is the end of the Native Code, the Kanak people are granted citizenship and enter institutions. It also marks New Caledonia’s second missed opportunity to become independent since in the 1958 constitutional referendum where the electoral roll was predominantly Kanak.

Under the influence of the Catholic and Protestant churches supported by the European section of the Union Calédonienne (UC) party, this party opted for YES, and therefore to remain within the French Republic. The framework law or autonomy law was in turn put in place.

● 1963-1968 and 1975-1984: Abolition of the framework law and birth of the Kanak pro-independence movement. 1975 was the year of the “Mélanésia 2000” cultural revolution, and the creation of the Front Indépendantiste in 1979.

● 1984 – 1988: It was the semi-failure of the Nainville-les-Roches discussions, the creation of the FLNKS, and the Kanak nationalist insurrection and revolts which lasted four long years.

● 1988 – 1989: [This] was the year of the signing of the Matignon Agreement and one year [later] the murder of Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Yeiwene Yeiwene since they did not have the FLNKS mandate to sign this agreement. An agreement which aimed to restore peace and initiate the rebalancing, but not to settle the issue of independence.

● 1988-1998-2018: the country enters a process of emancipation and decolonisation with the Matignon and Nouméa agreements by having “rebalancing” and “the impartiality of the state” as guiding principles.

● 2018-2022: this was the series of three referenda which resulted, according to France, in three NOs to full-sovereignty and independence. A progression of the YES to full sovereignty and independence between the first and second consultations is, however, notable. The third one is not recognised as politically legitimate by the FLNKS and its regional and international support due to 60 percent of non-participation, which includes the almost entirety of the Kanak people.

This explains the procedure at the International Court of Justice at The Hague. It is possible to estimate that the participation of the Kanak population to a third referendum organised in normal and transparent conditions, with an impartiality of the State would have allowed the country’s achievement of independence.

However, it marked the third missed opportunity to reach independence in our chaotic history of relations with France.

This brief historical reminder traces a trajectory that began with the arrival of the Europeans in Oceania in 1774 and which will continue until the achievement of full sovereignty in the coming years as part of a renewed relationship with France and Europe for a country that will be fully integrated in its geographical area. This has been its history for 3000 years, and this will be its future.

Indeed, experience has demonstrated that in the history of decolonisation in the Maghreb region, in Asia, in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world: the colonised never give up on the question of their asserted identity. It is the same for our people which have always fought against an oppressive and forced assimilatory system.

While it fought against a system, the Kanak people respect France and its inhabitants. France has a history that we respect: it is a great nation which defends universal values. Moreover, hundreds of our youth have given their life during the two world conflicts. France has brought us [the] Catholic and Protestant religion[s] as well as education. That is what the preamble of the Nouméa Agreement acknowledges.

Due to being unheard in its struggle against a colonial system, we can consider that the nationalist movement which started in the early 1970s was a response to the abolition of the framework law put in place by the 1958 constitution, then removed in 1963. The movement peaked in 1984-1988, with the painful events of Ouvéa, where the special troops of the French armed forces intervened to maintain the public order.

The number of Kanak leaders having lost their life during this period up until 1989 is significant, especially considering their quality and our small population. In light of this dead-end situation, the handshake between Jean-Marie Tjibaou, Jacques Lafleur, and Michel Rocard, as planned, allowed for peace to be restored.

And the rebalancing included in the Matignon Agreement approved by the national referendum of 1988.

This ten-year period between 1988 and 1998 was meant to be an opportunity for a more balanced development of the territory. The no. 1 text of the Matignon Agreement is entitled: “The condition for a lasting peace — The impartial State at the service of all.” The press release of June 26, 1988, also insists on this point: “The impartiality of the State must be guaranteed, the security and protection of all must be ensured”.

And on August 20, the Minister of Overseas Departments and Territories, Louis Le Pensec, declared before the agreement signing ceremony: “France can only be a referee if its spoken word inspires trust”.

In 1998, the Matignon Agreement gave way to a new agreement, the Nouméa Agreement, which won the support of the Kanak people but was rejected by the non-independence majority of the South[ern] Province. This agreement has received an almost unanimous approval from the Kanak people for several reasons:

– It maintained peace and allowed for the continuation of rebalancing policies;

– It allowed the construction of a project of society that would take colonialism

into account, following the Nainville-les-Roches Agreement in 1983; [and]

– Its preamble and guidance document de facto recognised Kanak identity and committed to the establishment of a new governance of New Caledonia, in the form of a sui generis collectivity with autonomy, in a perspective of independence.

New Caledonia, whose vocation for independence was recognised following the 1988 national referendum, was taking the path of the construction of a common destiny resting on a “Caledonian citizenship” and the irreversibility of the process of decolonisation and emancipation.

Thus, for the colonised Kanak people, the responsibility of the State as the third partner of the Nouméa Agreement is to guarantee this irreversible and sincere process, allowing New Caledonia to endorse its vocation to be a sovereign state, like the other sovereign states in the region. That is the meaning of the massive YES which was given by the Kanak people at the referendum to ratify this agreement on November 8, 1998.

It was the same for the national referendum of November 6, 1988. Under no condition can these two referenda be considered a reason for yet another status of integration of New Caledonia within France.

For the Kanak people, the process of self-determination must continue to follow up on the two referenda of 2018 and 2020. The Nouméa Agreement, which remains the basis on which the future of New Caledonia must be permanently built and sealed, is clear and unambiguous both in the preamble and the guidance document: Decolonisation is the way to rebuild a sustainable social bond between the communities that live in New Caledonia.

A new step must be taken to mark the full acknowledgement of Kanak identity, conditional to the reviewing of the social relationship between all the communities that live in New Caledonia and through the sharing of sovereignty with France before the full sovereignty of the country to be.

The culminating point of this Agreement is completely unambiguous because: “The State recognises the vocation of New Caledonia to benefit from a complete emancipation at the end of this period.” This Agreement will then remain at its last development stage without the possibility of going back in the event that the consultations do not lead to the new political organisation suggested. This irreversibility being a constitutional guarantee.

However, based on the decisions concerning the third referendum specifically, and the statements made by French government officials, the Kanak people observe that once again, the French State never follows through with its promises, and that in the last moment, it systematically aligns its interest as a “great power” to the French population it has settled in New Caledonia.

It was the case in 1963, when the French government unilaterally decided to cancel the framework law which had granted a wide autonomy status to New Caledonia, thus reflecting General De Gaulle’s desire to rely on New Caledonia and French Polynesia for France’s ambitions as a great world power. It also reflected the wishes of the [New] Caledonian colonial Right. This rupture unilaterally decided by Paris, created the conditions for the birth of Kanak nationalism from the 1970s, followed by its radicalisation in 1984-1988.

Today, almost forty years after 1984, it would seem that we are witnessing the same scenario, especially since the use of the concept of Indo-Pacific, with a renewed alliance between the President of the Republic and the Caledonian loyalists. Clearly, since 2021 and the Minister [Sébastien] Lecornu, the organisation of the third referendum has been the scene of the tipping of the State’s position towards the “No to independence” camp, undermining the very principles of the Matignon and Nouméa Agreements, the impartial State at the service of all, which resulted in a deadly loss of trust.

Since the possession of the islands by France, everything is done or organised based on French, European or Western norms, usages, traditions, or social structures, with an almost blind application of them in the context of a traditional society that is fundamentally different. Thus, basic organisations, structures, concepts, or processes, which are not that of Oceanian societies, continue to be imposed, without question as to the degree of constraint or acceptation that it implies.

However, this society, like any Oceanian society, carries deep values, drawing on the spiritual world, nourished by the sacred and inhabited by a way of thinking in harmony with nature and the cosmos as it has been valued, anchored mythological corpus on par with the great Mediterranean civilizations. We have not invented all this, it has been made explicit and rehabilitated by academia and anthropological research.

For a long time, the representatives of the Kanak people, whether it be the great chiefs, political leaders, or religious leaders have asked the question “but why does France, the governing power, not hear us?” It remains deaf to our points, to what the Kanak people wants, because it is its right to recover its lost sovereignty. But France does not think so and does not respect the recommendations made by the United Nations. It does exactly the opposite or interprets what is presented to it within the framework of the defence of superior national interests.

Could France, for once, carry a process of decolonisation through? This unfinished process of decolonisation carried on into the third referendum, which the FLNKS considers a “stolen” referendum. Has France forgotten the history of the colonisation of this people

and of its millennial civilisation?

The Melanesian civilisation is not an invention of the mind, it was demonstrated, scientifically confirmed by the community of researchers in the field of anthropology. Indeed, within the context of anthropology and approaching “deep nthought”, academic research led on the path of understanding the spirit of man and his relationship with the material and spiritual world around him. The aforementioned work provides for the first time an exploration and in-depth reading of the mythical thought of the Kanak people; thus, this research establishes the sacralising vision of ancient Kanak myths and an integral landscape of life in the Kanak world, the visible and the invisible; rehabilitating the power of myth in the 21st century and by attributing it an academic dignity, it valorises the cultural capital of people.

This work has been welcomed as a true exploration, both novel and original, it underlines the height and strength of Kanak deep thought and highlights fundamental themes such as cosmological knowledge, the power of symbols and archetypes, etc. This observation encourages the total recognition of the qualitative aspect of this people. However, the current evolution is not going in this direction and has never acknowledged these immaterial and intellectual resources. Therefore, its formalisation and institutionalisation is suggested, since the State cannot ignore the fundamental elements of Kanak society which can infer the proclamation of a prior sovereignty.

One cannot deny that the French presence in New Caledonia, the successive leadership and the institutional changes have never integrated in writing or in speech the “pre-eminence, the full and legitimate connection to their land (existential and ontological link, startling for the Cartesian mind, Kanak belong to their land, land does not belong to them) and the sacred and inalienable character of the presence and existence of the Kanak people, as well as the sovereignty they possess: the later comes from the people and is complementary to the immaterial heritage . . .”

On this note, customary senators expressed their deep gratitude to an academic researcher in structural anthropology, whose novel work was welcomed as having valued and sacralised the fundamentals which structure Kanak civilisation. This original contribution fills a gap and demonstrates that “others” can understand, respect, and give the Kanak people their essential and existential values back. Above all, this contribution disrupts the one directional relation, which prevents the establishment of a real exchange, and which leads to forceful imposition, regardless of the qualities and values of the other. We seriously believe that France can take a step that it has never taken before to show that it is a great nation capable, like the Kanak who welcomes others, of recognising “a timeless and original sovereignty”, an essential condition for sharing in acceptance and understanding.

Indeed, it constitutes a new approach because a part of Kanak civilisation was destroyed in its anthropological foundations and its sociocultural organisation by the violence of French possession and the imposition of a “pax romana” without any counterpart. The impacts are known: the annihilation of the history which precedes September 24, 1853, the loss of identity in relation to languages, land, culture, beliefs, etc. Kanak people’s ancestral land was considered “terra nullius”. This “terra nullius” status was assigned to make it “lawful” for better armed countries which pretended to be “more civilised” to seize, colonise and exploit territories and resources. That is in spite of the fact that, in our traditions, not one centimeter of land or maritime territory escaped the ontic link of belonging between the human and their land.

But in the meantime, the impacts on the being and doing of Kanak people have been of a great violence and these harms are still present in 21st century Kanak society. Some of these impacts have been acknowledged notably in the preamble of the Nouméa Agreement, but no solution followed, through a holistic approach which could have defined some “just” measures to implement so that the Kanak people could recover its dignity.

It is time for France to react because in New Caledonia, a sly colonialism or neocolonialism is currently at play, attempting to erase and negate the natural sovereignty of the Kanak people on its territory, condemning it to eternally look for a lost paradise. We do not want to die assimilated like a sugar cube in water and we will resist to survive. Fortunately, some moral voices make themselves heard to denounce this unjust system, as is the case with the Vatican.

In its “colonial” history, the Vatican shared discovered lands with different European Christian countries, among which Portugal, Spain, France, etc. It ended up ubi et orbi declaring the abandonment of the doctrine of discovery, which operated from the 16th century and provided a framework to lay possessive claims, to appropriate and to colonise, due to the destruction, damage, and other ills of colonisers. More recently, Pope Francis declared in a message addressed to the participants of the “colonisation and neocolonialism: a social justice and common good perspective” forum, which took place on March 30th and 31st, 2023 that neocolonialism is sly, that it is a crime, and that there isn’t any possibility of peace in a world that rejects some people in order to oppress them.

We even remember the unforgettable sentence marked by the “presidential” seal, of candidate Emmanuel Macron in Algeria, stating that colonisation is a crime against humanity. This gives more weight to the papal message. Restorative action is thus unavoidable and must lead to a deep reflection: Which people has suffered? To whom do we owe reparation and apology before imposing and controlling?

We do not ask for pity, nor do we beg or repent, a confessional notion. We only ask for justice through a holistic and recognised approach, that of transitional justice with its four pillars, to reinvigorate a damaged people, which drags generation after generation, the negative impacts on its being and its doing, as Solgenystine and other experts remind us on the topic of colonialism.

But we are also aware of the “cultural” difficulty for the great colonising countries to go in the direction of colonised countries. As evidence, in the work of French anthropologist François Pouillon on this issue:

Nations states hardly appreciate Native peoples, even more so when the latter

manifest some inclination toward autonomy, or worse, independence. At stake is the

power of sovereign states over the territories they govern and from which they most

often exploit the Native populations which are marginal in their eyes. If they resist,

they break the law and expose themselves to economic, juridical or even military

sanctions.

Contemporary centralised states are more so convinced of their efficacy and legitimacy as they promote ideologies and values which they are always proud of: the development of their technical and medical knowledge, the “universality” of their confessional or secular beliefs, their “influence” in the world and, at last, their advanced position in the evolution of humankind, all of this supported, more prosaically, by a solid armament.

Native peoples, in their emphasis on their own territories, memories, institutions and knowledges, would only slow them down on their path to perfection.

This tyrannical self-satisfaction feeds on the conviction, as François Pouillon underlines, that “if others, abroad, sometimes have an enviable quality of life, in their closeness to nature and the spiritual warmth of their group (which, however, does not protect them from bloody dictatorships, ethnic cleanings, natural disasters and great modern pandemics), they are, we believe, in a pitiful political state and remain, after all, ‘backward’.” (Anthropologie des petites choses, Le Bord de l’eau, 2015)

Colonial attitudes feed off this “naïve evolutionism” from which contempt originates. From the lack of consideration to enslaved people in the Code Noir (royal decree passed in 1685 aiming to define the conditions of slavery and its practices in the French colonies) to the dehumanisation of Jewish and Tzigane [Roma] people in extermination camps, through the stigmatisation of “primitive” people and other “indigènes” of the colonies, the same deadly chant is sung: May impure blood water the fields of the civilization we embody.

These references are not historical since, today, Amazonia has been transformed into a gigantic inferno where the last Indians die, while Uighurs, Rohingya, Roma, Aboriginal people, African Americans, Native Americans and many others suffer a thousand deaths under the rule of nation-states convinced of being at the top of social and human progress.

Will Kanaks of New Caledonia also pay the price of the narcissism of the powerful? And thus, of France?

“Rebalancing” policies all over the Pacific, Native populations have already historically undergone a spectacular demographic decline (due to epidemics, massacres, poisonings), land spoliation from non-Indigenous people, both rural and urban, exclusion from the benefits of new economic initiatives (mining, extensive breeding, exportation) and the moral attacks of Western monotheisms.

The paradox of New Caledonia is that France has recognised parts of its faults by committing, from 1988, to important “rebalancing” policies aimed primarily at Kanaks. Michel Rocard, when he was Prime Minister from 1988 to 1991, then Lionel Jospin, from 1997 to 2002, also supported the industrial ambitions of pro-independence leaders by enabling them to acquire a mine and to successfully extract, process and export nickel. At the same time, strong support for the expression of Kanak identity has marked the last thirty years with the creation of the Tjibaou Cultural Centre in May 1998, the revival of the Customary Senate [Kanak advisory assembly] and taking into account the Indigenous point of view in the courts.

These significant developments, which have never been questioned by the successive governments of the French Republic, have noticeably appeased the minds and improved the daily life of all Caledonians in general, and Kanaks in particular.

They were combined with unprecedented institutional measures: the scheduling of three referenda for self-determination, the creation of a special electoral roll used for polls open solely to Caledonians who had settled before 1994 and the urge to all the communities living in the archipelago to elaborate a “common destiny”. Alternative forms of sovereignty.

This momentum did not lead to New Caledonia’s access to full sovereignty in the first referendum on November 4, 2018, but it signaled a surprise surge in votes in favour of independence (43.3 percent), a cause which Caledonian of European, Asian or Oceanian descent have evidently joined. This trend was confirmed on October 4, 2020, with 47 percent of the population expressing their wish for New Caledonia to become independent. If this progression is significant, these results won’t change the outcome. The issue is not purely electoral or numerical.

It refers to much deeper forces. Oceanians, despite being victims of a denial of existence, have created social organisations, practices and knowledge related to their doing and being that are specific to them. Through relations to land, legitimacies to power and counter power, strategies of political and matrimonial alliances, whether near or far, connections to the past, and visual and narrative creations, they have developed an alternative form of sovereignty to the monolithic and absolute one that is glorified by nation-states. The challenge of French and British colonisation has matured this nuance and complex political thought, which is a source of resistance and projects for the future. These gains are ineradicable and will not be phased by the ephemeral results of a referendum.

In this context, how can we forge a genuine dialogue?

It seems to us that it is high time for the governing authority to look at the “other” in order to have a mutual understanding, the basis of trust to create, promote, and walk together with the ability and willingness to share a “modus operandi” through the discussions and negotiations to come on the topic of other forms of governance.

Consensus proves to be a fundamental element in the important choices that we had to make for the evolution of New Caledonia in light of the challenges of 21st century.

You have no other choice than to integrate this practice specific to the Pacific or miss out on a successful statutory development project for New Caledonia.

Madam Prime Minister, your government would gain from being in a “win-win” approach, because everyone can assess what New Caledonia represents in this part of the world. We are ready to discuss it.

Building new relationships of trust between our two countries, committing to stability for the populations which have chosen to participate to New Caledonia’s prosperity, and lastly, mastering the stakes, notably environmental, that we will have to face are all challenges that we are willing to undertake. Therefore, the unique trajectory assumed by the FLNKS for the accession to full sovereignty and independence offers the outline that we wished to present to you.

The past 30 years of social stability have provided a conductive environment for the unprecedented development of our country. The irreversible process of decolonisation put in place by the Nouméa Agreement has placed New Caledonia in front of its growing responsibilities, leading us to be standing at the doors of the “concert of nations”.

Considering our emancipation process, the FLNKS believes that we are ready to assume the attributes of our sovereignty. Through a co-construction approach, we propose that the adoption of a political treaty enabling to seal a political basis for this final phase of statutory evolution be studied.

This political agreement will guarantee:

● Reaching an independence bilaterally negotiated with the governing power;

● The continuation of the irreversible process of decolonisation of New Caledonia;

● Obtaining an ultimate process that implements a programme of accession to

full sovereignty and independence; and

● Constitutionalising the political agreement and the accession to independence status, which includes the transition phase, the sovereignty act and the proclamation of the birth of a new state.

Since 1986, New Caledonia has been on the UN list of non-self governing territories. This acknowledgement on the international stage guarantees us rights without which our deepest aspirations would not have been heard. And as long as our ultimate conviction will not be respected, we will continue to make our struggle known.

Madam Prime Minister, this year will mark the 25th year since the Nouméa Agreement. It is our duty to cultivate this consensual state of mind, which has guided all the stakeholders to this juridical innovation that recognised “the shadows of colonisation”.

Madam Prime Minister, we will have to stand by the choices we make for our future generations. As far as we are concerned, it is our duty never to surrender our right to independence and we are convinced that the French State can succeed in the statutory evolution of New Caledonia, within the context of the UN’s Fourth International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism.

To conclude, Madam Prime Minister, this long introduction allows us to place in front of you a historical and political trajectory for the country to access full sovereignty and independence is a logical destiny. We would like to know the ambitions of the central government.

Thank you for your attention.

Roch Wamytan

Head of Delegation

This statement has been lightly edited for publication style.