COMMENTARY: By Gavin Ellis

It is unlikely that the Mayor of Auckland, Wayne Brown, took any lessons from the city’s devastating floods but the rest of us — and journalists in particular — could learn a thing or two.

Brown’s demeanour will not be improved by a petition calling for his resignation or media columnists effectively seeking the same. He will certainly not be moved by New Zealand Herald columnist Simon Wilson, now a predictable and trenchant critic of the mayor, who correctly observed in the Herald on Sunday: “In a crisis, political leaders are supposed to soak up people’s fears…to help us believe that empathy and compassion and hope will continue to bind us together.”

Wilson’s lofty words may be wasted on the mayor, but they point to another factor that binds us together in times of crisis. It is communication, and it was as wanting as civic leadership on Friday night and into the weekend.

- READ MORE: Auckland deputy mayor talks up media role in disasters in wake of mayor Brown ‘drongos’ text

- LISTEN TO RNZ MORNING REPORT: ‘I’m talking to you now, I’ll talk to you at any time’ – Auckland deputy mayor Desley Simpson

- Other Asia Pacific Reports on the North Island floods

Media coverage on Friday night was limited to local evacuation events, grabs from smartphone videos and interviews with officials that were light on detail. The on-the-scene news crews performed well in worsening conditions, particularly in West Auckland.

However, there was a dearth of official information and, crucially, no report that drew together the disparate parts to give us an over-arching picture of what was happening across the city.

I waited for someone to appear, pointing to a map of greater Auckland and saying: “These areas are experiencing heavy flooding . . . State Highway 1 is closed here, here and here as are these arterial routes here, here, and here across the city . . . cliff faces have collapsed in these suburbs . . . power is out in these suburbs . . . evacuation centres have been set up here, here, and here . . . :

That way I would have been in a better position to understand my situation compared to other Aucklanders, and to assess how my family and friends would be faring. I wanted to know how badly my city as a whole was affected.

Hampered by deadlines

I didn’t get it from television on Friday night nor did I see it in my newspaper on Saturday. My edition of the Weekend Herald, devoting only its picture-dominated front page and some of page 2 to the flooding, was clearly hampered by early deadlines. The Dominion Post devoted half its front page to the storm and, with a later deadline, scooped Auckland’s hometown paper by announcing Brown had declared a state of emergency.

So, too, did the Otago Daily Times on an inside page. The page 2 story in The Press confirmed the first death in the floods.

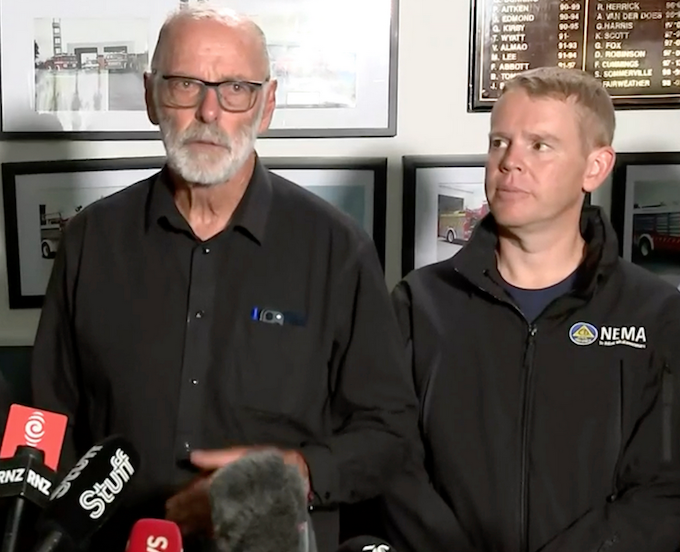

I turned to television on Saturday morning expecting special news programmes from both free-to-air networks. Zilch . . . nothing. Later in the day TV1 and Newshub did rise to the occasion with specials on the prime minister’s press conference, but it seems a small concession for such a major event.

Radio fared better but only because regular hosts such as NewstalkZB’s All Sport Breakfast host D’Arcy Waldegrave and Today FM sports journalist Nigel Yalden rejigged their Saturday morning shows to also cover the floods.

RNZ National’s Kim Hill was on familiar ground and her interview with Wayne Brown was more than a little challenging for the mayor. RNZ mounted a “Midday Report Special” with Corin Dann that also tried to break through the murk, but I was left wondering why it had not been a Morning Report Special starting at 6 am.

Over the course of the weekend the amount of information provided by news media slowly built up. Both Sundays devoted six or seven pages to the floods but it was remiss of the Herald on Sunday not to carry an editorial, as did the Sunday Star Times.

It was also good to see Newsroom and The Spinoff — digital services not usually tied to breaking news of this kind — providing coverage.

“Live” updates on websites and news apps added local detail but there was no coherence, just a string of isolated events stretching back in time.

Inadequate information

Overall, the amount of information I received as a citizen of the City of Sails was inadequate. Why?

Herein lie the lessons.

News media under-estimated the impact of the event. Although there were fewer deaths than in the Christchurch earthquake or the Whakaari White Island eruption, the scale of damage in economic and social terms will be considerable. The natural disaster warranted news media pulling out all the stops and, as they did on those occasions, move into schedule-changing mode (and that includes newspaper press deadlines).

Lesson #1: Do not allow natural disasters to occur on the eve of a long holiday weekend.

Media were, however, hampered by a lack of coherent information from official sources and emergency services. Brown’s visceral dislike of journalists was part of the problem but that was not the root cause. That fell into two parts.

The first was institutional disconnects in an overly complex emergency response structure which is undertaken locally, coordinated regionally and supported from the national level. This complexity was highlighted after another Auckland weather event in 2018 that saw widespread power outages.

The report on the response was resurrected in front page leads in the Dominion Post and The Press yesterday. It found uncoordinated efforts that did not use the models that had been developed for such eventualities, disagreements over what information should be included in situation reports, and under-estimation of effects.

Massey University director of disaster management Professor David Johnston told Stuff he believed the report would be exactly the same if it was recommissioned now because Auckland’s emergency management system was not fit for purpose — rather it was proving to be a good example of what not to do

Lesson #2: Learn the lessons of the past.

The 2018 report did, however, give a pass mark to the communication effort and noted that those involved thought they worked well with media and in communicating with the public through social media.

Can the same be said of the current disaster response when there “wasn’t time” to inform a number of news organisations (including Stuff) about Wayne Brown’s late Friday media conference, and when Whaka Kotahi staff responsible for providing updates clocked-off at 7.30 pm on Friday?

Is it timely for Auckland Transport to still display an 11.45 am Sunday “latest update” on its website 24 hours later? Is it relevant for a list of road closures accessed at noon yesterday to have actually been compiled at 7.35 pm the previous night? Why should a decision to keep Auckland schools closed until February 7 cause confusion in the sector simply because it was “last minute”?

Lesson #3: Ensure communications staff know the definition of emergency: A serious, unexpected, and potentially dangerous situation requiring immediate action.

There certainly was confusion over the failure to transmit a flood warning to all mobile phones in the city on Friday. The system worked perfectly on Sunday when MetService issued an orange Heavy Rain Warning.

It appears that emergency personnel believed posts on Facebook on Friday afternoon and evening were an effective way of communicating directly with the public. That is alarming because social media use is so fragmented that it is dangerous to make assumptions on how many people are being reached.

A study in 2020 of United States local authority communication about the covid pandemic showed a wide range of platforms being used and the recipients were far from attentive. The author of the study, Eric Zeemering, found not only were city communications fragmented across departments, but the public audience selectively fragmented itself through individual choices to follow some city social media accounts but not others.

In fact, more people were passing information about the flood to each other via Twitter than on Facebook and young people in particular were using TikTok for that purpose. Media organisations were reusing these posts almost as much as the official information that from some quarters was in short supply.

Lesson #4: When you need to communicate with the masses, use mass communication (otherwise known as news media).

Mistakes will always be made in fast changing emergencies but, having made a mistake, it is usual to go the extra yards to make amends. It beggars belief that Whaka Kotahi staff would fail to keep their website up to date on the Auckland situation when it is quite clear they received an enormous kick up the rear end from Transport Minister Michael Wood for clocking off when the heavens opened.

Or that Auckland Transport could be far behind the eight ball after turning travel arrangements for the (cancelled) Elton John concert into a fiasco.

After spending Friday evening holed up in his high-rise office away from nuisances like reporters attempting to inform the public, Mayor Brown justified his position with a strange definition of leadership then blamed others.

Sideswipe’s Anna Samways collected a number of tweets for her Monday Herald column. Among them was this: “Just saw one of the Wayne Brown press conferences. He sounded like a man coming home 4 hours late from the pub and trying to bull**** his Mrs about where he’d been.”

Lesson #5: When you’re in a hole, stop digging.

Dr Gavin Ellis holds a PhD in political studies. He is a media consultant and researcher. A former editor-in-chief of The New Zealand Herald, he has a background in journalism and communications — covering both editorial and management roles — that spans more than half a century. Dr Ellis publishes the website knightlyviews.com where this commentary was first published and it is republished by Asia Pacific Report with permission.