COMMENTARY: By Mary Argue of the Wairarapa Times-Age

In 2016, I was on a yacht in the Bahamas.

Every morning I woke surrounded by postcard-perfect azure water — so crystal clear you could count the sharks sweeping the seafloor.

From my porthole in the laundry, my 1x2m kingdom, I would watch the rain clouds gather in the afternoon and a breeze toss the palm trees 30 metres from anchor.

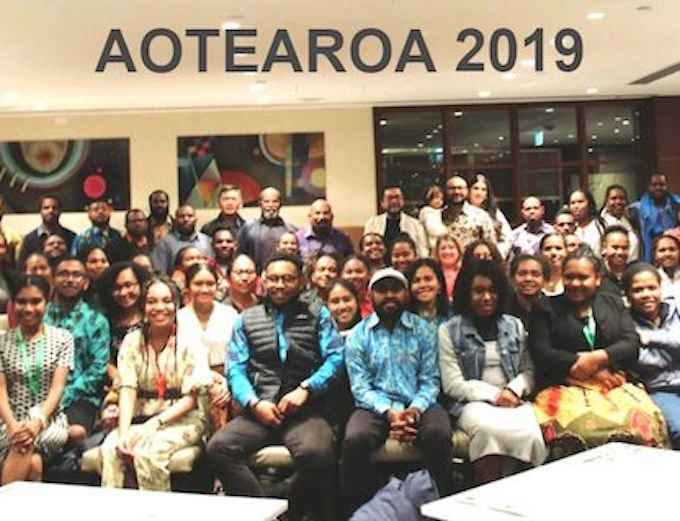

- READ MORE: Papuan students succeed in NZ – ‘the golden generation from Papua’

- Other West Papua education reports

It was below-deck before the reality TV series existed — Downton Abbey for the 21st century.

I flew home in March, surprising my family with an early return. It turned out being the help on a luxury yacht was not for me.

When I arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand, however, the surprise was mine. There was no room at the inn.

My family had taken in two West Papuan boys who were enrolled at the local high school.

They were part of a group of students at the start of a six-year scholarship programme funded by the Indonesian government.

I bunked in with my brother, sharing a room for the first time since I was 10 years old.

My new Papuan ‘brothers’

The Papuan boys, my new brothers, had shivered through the Wellington summer. Their English was improving daily, but conversation was still a struggle.

Every day they woke and sprinted to catch the school bus. There they spent the whole day surrounded by fast-talking, monotone English voices. At the end of it, they were exhausted but still chipped in at the dinner table, cracking jokes and bravely consuming the foreign cuisine before them.

Our family grew from six to eight.

My youngest brother relished no longer being the baby and took our exchange students under his wing.

After enormous peer pressure, the boys taught us some choice Indonesian swear words, but our ability in their language didn’t progress much beyond that.

They graduated high school, turned 18, went out clubbing, played for the local football team. They embraced New Zealand life and all our family’s quirks.

After four years, they moved from Wellington and enrolled in tertiary education.

This Christmas, they schooled us all in volleyball.

Embassy letter brings bad news

At about the same time, the Indonesian government sent a letter to the embassy in New Zealand.

In it was a list of Papuan students who had “fallen behind” in their studies. These students, they said, would need to be sent home immediately.

One of our Papuan brothers is on this list, a young man almost at the end of his study.

He has an apprenticeship with a local builder lined up, by all accounts, is excelling in his field, as are the other 38 students listed.

The list of names is the fallout of law changes in Jakarta in 2021 that reallocated money away from the Papuan provincial government to the districts. The scholarship fund for the students has dried up.

These victims of politics, however, have taken a stand.

Despite no longer receiving the money to pay their rent and food, they have told the authorities that they will not return and have demanded dialogue with the Indonesian President, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo.

The Asia Pacific Report has investigated the human rights issue, but aside from one or two other outlets, by and large, the New Zealand media have ignored it.

Times-Age will be joining the debate.

Mary Argue is a Wairarapa Times-Age journalist where this commentary was first published. It is republished with permission.